Khalid ibn al-Walid: A War Analysis

Khalid's career is marked by a unique distinction shared perhaps only with Genghis Khan: remaining undefeated throughout his extensive military command.

I. Introduction: Khalid ibn al-Walid, The Sword of Allah

A. Overview

Khalid ibn al-Walid (circa 585–642 CE), a member of the influential Banu Makhzum clan of the Quraysh tribe in Mecca 1, stands as a towering figure in military history. His career is marked by a unique distinction shared perhaps only with Genghis Khan: remaining undefeated throughout his extensive military command.4

Khalid played an indispensable role in the survival and expansion of the nascent Islamic state during the pivotal early 7th century. His campaigns during the Ridda Wars consolidated Muslim control over Arabia, and his subsequent invasions of the Sasanian Persian and Byzantine Roman empires led to staggering territorial gains in Iraq and Syria (the Levant) within a remarkably short period.1

His military prowess earned him the honorific title Sayf Allah (The Sword of Allah), reportedly bestowed upon him by the Prophet Muhammad himself following the Battle of Mu'tah.2 His victories against the two great superpowers of the age fundamentally altered the geopolitical landscape of the Near East.6

B. Scope and Methodology

This article aims to provide a comprehensive and analytical account of Khalid ibn al-Walid's military career, focusing specifically on the battles and campaigns he led or significantly influenced. Internet sources usually mention approximately 55 battles; however, historical Islamic sources often list over a hundred engagements, including minor skirmishes and individual duels in which Khalid participated.5

This study will concentrate on the major documented battles and campaigns, synthesising information from primary historical accounts and contextualising these events with insights from modern military historiography. Minor engagements may be grouped or summarised within the context of larger campaigns.

The analysis for each significant battle will cover, where sources permit:

- Forces: Estimated size and composition of both Khalid's army and the opposing forces, including notable commanders.

- Context: Geographical location, date, prevailing conditions, and strategic background.

- Tactics: Key strategies and maneuvers employed by Khalid and his opponents.

- Progression: A narrative of the battle's key phases and turning points.

- Outcome: The result of the battle and its immediate consequences.

- Sources: Citation of the primary and secondary historical sources providing the information.

The work follows a chronological structure, examining Khalid's pre-Islamic military activities, his role in the Ridda Wars, his campaigns in Sasanian Iraq, and his leadership in the conquest of Byzantine Syria. It will conclude with a thematic analysis of his military doctrine and a discussion of his controversial dismissal and enduring legacy.

C. Note on Sources

Reconstructing Khalid ibn al-Walid's military career relies heavily on early Islamic historical texts. Among the most crucial primary sources are:

- Al-Tabari (Abu Ja'far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari, 839–923): His monumental Ta'rikh al-rusul wa'l-muluk (History of Prophets and Kings) serves as a foundational source, offering detailed narratives of the Ridda Wars and the subsequent conquests in Iraq and Syria. It is considered the most important universal history produced in the Islamic world.14 His work is frequently cited for details on battles like Buzakha, Yamama, Chains, River, Walaja, Ullais, Hira, Zafar, Dawmat al-Jandal, Firaz, Damascus, Hazir, and the circumstances of Khalid's dismissal.4

- Al-Waqidi (Abu 'Abdullah Muhammad ibn 'Umar al-Waqidi, 747–823): His Kitab al-Maghazi (Book of Campaigns) provides rich, albeit sometimes debated, details, particularly concerning the Prophet Muhammad's campaigns and the early Syrian conquests, including battles like Ajnadayn, Damascus, and Yarmouk, as well as the siege of Jerusalem and Khalid's dismissal.4

- Al-Baladhuri (Ahmad ibn Yahya al-Baladhuri, d. 892): His Futuh al-Buldan (Conquests of the Lands) is invaluable for information on the conquests, administration, and specific battle details, including Buzakha, Yamama, Naqra, the Malik ibn Nuwayra affair, Ullais, Fahl, Ajnadayn, and Damascus.4

- Ibn Ishaq (Muhammad ibn Ishaq ibn Yasar, 704–767): His Sirat Rasul Allah (Life of the Messenger of God), primarily preserved through the recension of Ibn Hisham, is fundamental for early Islamic history, including Khalid's pre-conversion activities and early battles like Uhud and Mu'tah.4 The potential capture of his ancestor at Ayn al-Tamr adds a layer of connection.23

- Ibn Kathir (Isma'il ibn 'Umar ibn Kathir, 1300–1373): His comprehensive history, Al-Bidaya wa'l-Nihaya (The Beginning and the End), compiles and comments on earlier traditions, offering valuable perspectives on Khalid's dismissal, the Malik ibn Nuwayra incident, the Battle of Ullais, the siege of Emesa, and other events.4

- Other Early Sources: Information is also drawn from the works of Ibn Sa'd, Khalifa ibn Khayyat, Sayf ibn Umar, and others who documented the early Islamic period.1

Modern historical scholarship provides essential analysis, interpretation, and synthesis of these primary accounts. Key figures include:

- A.I. Akram: His detailed military biography, The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin Al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns, based on primary sources and battlefield visits, offers a crucial modern military perspective.4

- Hugh Kennedy, Fred Donner, David Nicolle: Leading Western scholars who provide broader context, critical analysis, and insights into the early Islamic conquests and the reliability of sources.18

Reconstructing these events involves navigating challenges inherent in early historical sources, including potentially conflicting narratives, numerical exaggerations, tribal biases, and the overlay of later theological or political interpretations.24 This work endeavors to present a balanced account by comparing sources and acknowledging areas of uncertainty.

The sheer volume and detail found in these early sources, despite their variations 14, underscore the profound impact Khalid ibn al-Walid had on his contemporaries and subsequent generations. The existence of multiple, sometimes conflicting, accounts reflects not only the complexity of the events but also the diverse perspectives within the early Muslim community and the various narrative traditions that sought to record his pivotal role.

This multiplicity itself speaks to his perceived significance. Furthermore, the relatively rapid emergence of detailed historical writing (ilm al-tarikh) and campaign literature (maghazi) in the centuries immediately following these conquests 14 suggests a strong awareness within the early Islamic community of the historical weight of these foundational moments.

The meticulous documentation of the Prophet's life and the exploits of key figures like Khalid was seen as essential for preserving the identity, legitimacy, and divine narrative of the nascent Islamic state.

II. The Crucible of Conflict: Early Engagements

A. Against the Muslims: The Battle of Uhud (March 625)

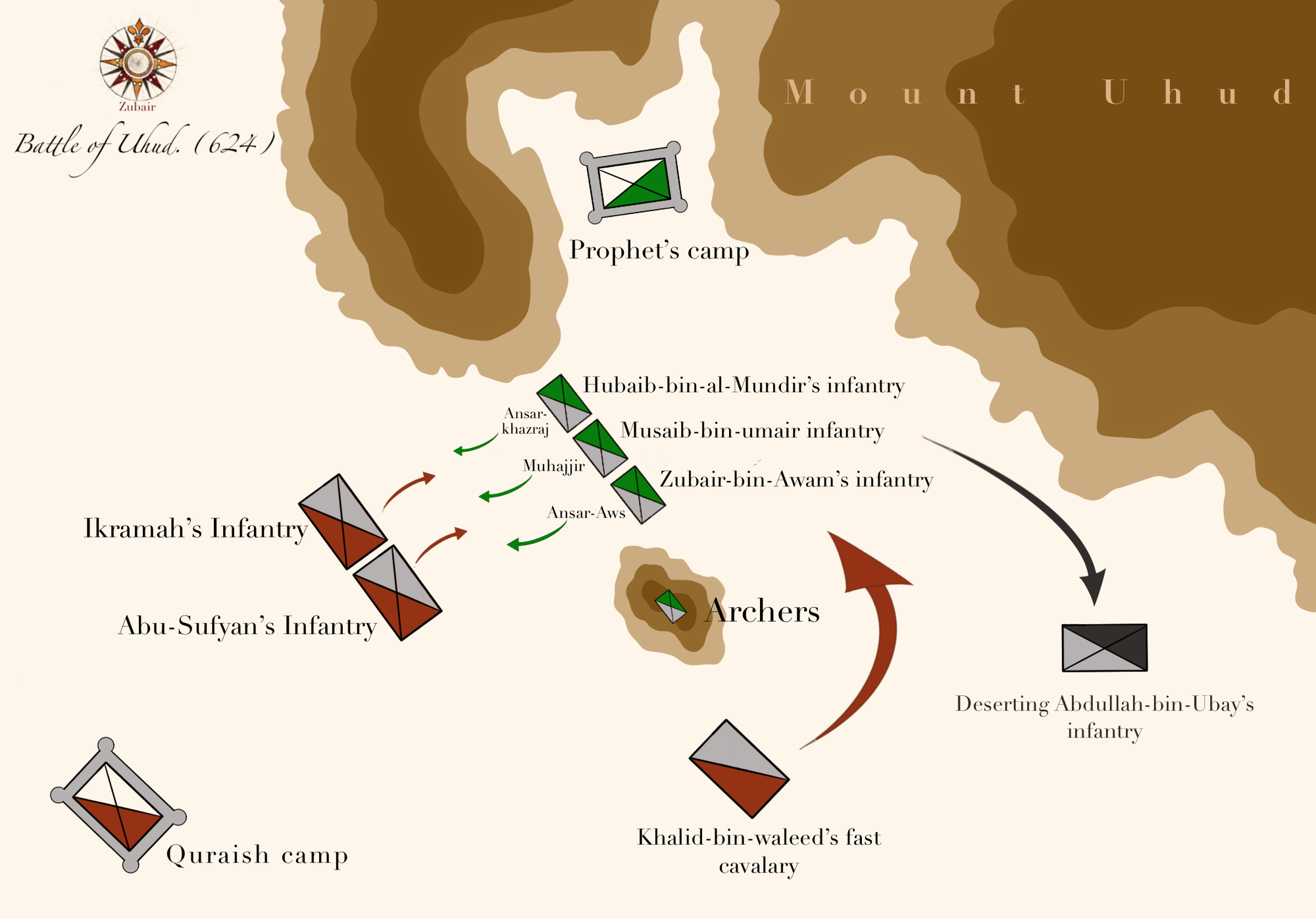

Khalid ibn al-Walid's first major appearance in the historical record is not as a Muslim commander, but as a key figure fighting against the forces of Prophet Muhammad. Following the Quraysh defeat at the Battle of Badr, the Meccan leadership, under Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, sought retribution.46 In March 625, a large Quraysh army, numbering approximately 3,000 men (including 1,450 infantry, 1,450 camel riders, and 100 cavalry), confronted a much smaller Muslim force of about 750 near Mount Uhud, north of Medina.46

Khalid ibn al-Walid commanded the crucial right flank of the Quraysh cavalry, with Ikrima ibn Amr commanding the left.3 The battle initially favored the Muslims, whose infantry pushed back the Meccan center. However, a critical error occurred when Muslim archers, positioned by Muhammad on a nearby hillock with strict orders to hold their ground, abandoned their post to pursue spoils from the seemingly defeated Meccan camp.1

Observing this tactical opening with keen military insight, Khalid seized the moment. He led his cavalry squadron in a swift and decisive maneuver, wheeling around the Muslim flank and charging into their now undefended rear.1 This unexpected attack threw the Muslim lines into disarray, encircling them and turning the tide of the battle decisively in favor of the Quraysh.46 Narratives describe Khalid riding through the ensuing chaos, inflicting casualties.1

The battle resulted in a tactical victory for the Quraysh, although they failed to press their advantage and eliminate the Muslim leadership or community.46 Muslim casualties were heavy (62-75 killed), including prominent figures like Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib.46 Uhud stands as the only significant military defeat experienced by Muhammad, and Khalid's "military genius" is widely credited for the Quraysh success.1

This engagement vividly demonstrated the tactical brilliance and opportunism that would later characterize his command under the banner of Islam. Primary sources for Uhud include the Sira literature (Ibn Ishaq/Hisham), Hadith collections, and Quranic commentary related to the battle.46

B. Conversion and Early Service for Islam (c. 627/629)

Despite his role at Uhud, Khalid ibn al-Walid embraced Islam a few years later, after the seige of Madinah. His conversion is generally dated to the period after the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah (628 CE), likely in the 7th or 8th year of the Hijra (c. 629 CE).3 According to some scholarly classifications of the Prophet's Companions based on the timing of their conversion, Khalid falls into a later category (Rank 10).4

His decision to join the Muslim community represented a significant surprise, bringing one of Mecca's most formidable military minds into the service of Islam.3 Upon converting, he reportedly asked Prophet Muhammad to pray for his forgiveness for his past actions against the Muslims.3 This conversion marked a profound shift, transforming a potent adversary into a dedicated defender and expander of the faith.

C. Battle of Mu'tah (September 629)

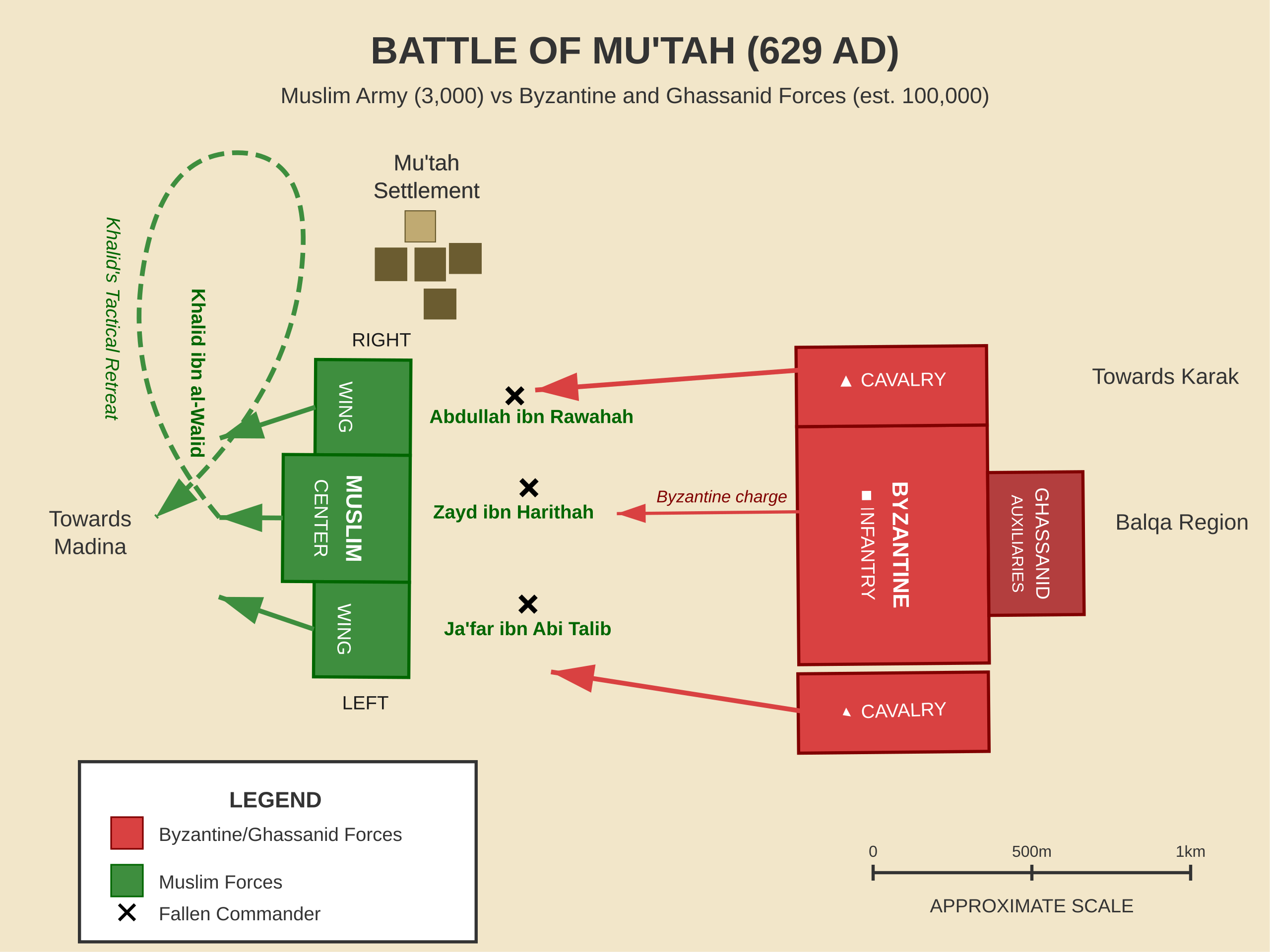

Soon after his conversion, Khalid participated in his first major expedition for the Muslims: the Battle of Mu'tah. This engagement, fought near modern Karak in Jordan, represented the first significant military encounter between the nascent Islamic state and the Byzantine Empire, or more likely, their Ghassanid Arab client allies.1 The expedition, numbering around 3,000 Muslims, was dispatched ostensibly to retaliate for the killing of a Muslim envoy by a Ghassanid chieftain.3

The Muslim force faced a vastly superior enemy; traditional sources give figures as high as 100,000 for the Byzantine/Ghassanid army, although these are likely exaggerations.48 The fighting was exceptionally fierce. The three commanders appointed in succession by Prophet Muhammad – Zayd ibn Haritha, Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, and Abdullah ibn Rawahah – were all killed.3 In this dire situation, with the army leaderless and facing annihilation, the command devolved upon Khalid ibn al-Walid.2

Khalid's actions at Mu'tah showcased his extraordinary tactical skill and composure under pressure. Recognizing the impossibility of victory against such overwhelming odds, he orchestrated a masterful tactical withdrawal. He reorganized the Muslim lines, used small detachments in maneuvers that created the illusion of arriving reinforcements, and skillfully disengaged his forces, saving the army from destruction.2 During the intense combat, Khalid is said to have broken nine swords, a testament to the battle's ferocity.3

Although Mu'tah was technically a defeat or stalemate in terms of failing to achieve the expedition's punitive objective, Khalid's successful extraction of the Muslim force was hailed as a major achievement. Upon the army's return to Medina, Prophet Muhammad praised Khalid's leadership and bestowed upon him the title Sayf Allah (Sword of Allah).2 This event was psychologically crucial. Confronting the might of the Byzantine frontier forces and surviving, coupled with the Prophet's explicit endorsement of Khalid, significantly boosted Muslim morale and cemented Khalid's reputation. It demonstrated that even the great empires were not invincible.

D. Conquest of Mecca (January 630)

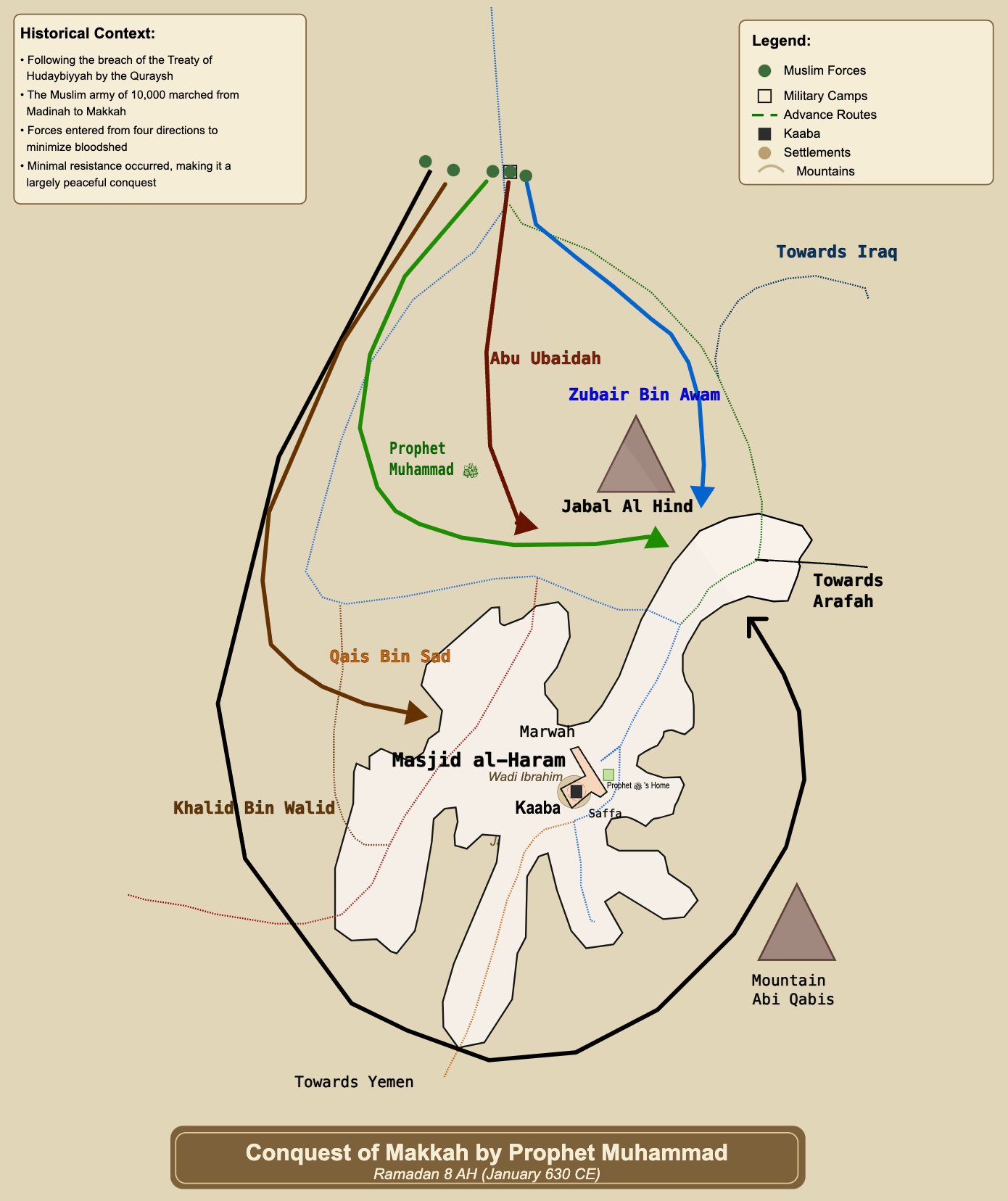

Khalid played a prominent role in the nearly bloodless Conquest of Mecca in 630 CE. When the Quraysh violated the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, Prophet Muhammad marched on the city with a large Muslim army. Khalid was given command of one of the main columns tasked with entering Mecca.2

While most columns entered without resistance, Khalid's contingent, advancing from the Lait region, encountered a pocket of opposition led by some die-hard Quraysh figures like Ikrima ibn Abi Jahl and Safwan ibn Umayya near Khandama. Khalid swiftly overcame this resistance, killing some opponents.3 His decisive action helped ensure the swift and largely peaceful submission of the city.2

Following the conquest, Muhammad dispatched Khalid to Nakhla to destroy the sanctuary and idol of al-Uzza, a major pre-Islamic deity worshipped by the Quraysh.3

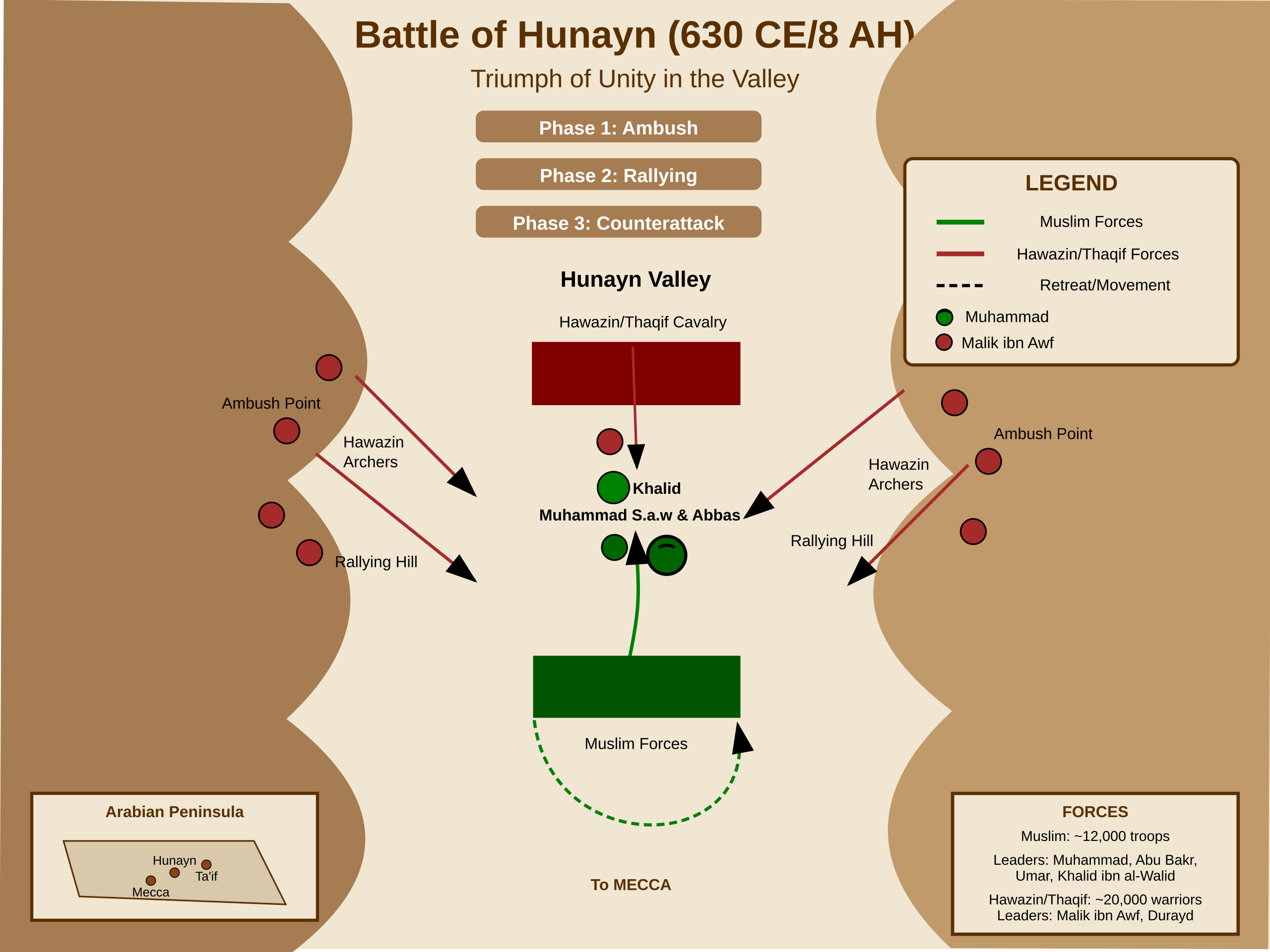

E. Battle of Hunayn (January/February 630)

Shortly after the conquest of Mecca, the Muslims faced a new threat from a confederation of Bedouin tribes, primarily the Hawazin and Thaqif, who gathered a large force to challenge Muhammad's authority. In the ensuing Battle of Hunayn, Khalid commanded the contingent of the Banu Sulaym tribe, which formed part of the Muslim vanguard.1

The Muslims were initially ambushed in the narrow valley of Hunayn and thrown into disarray. Khalid himself was wounded in this early phase of the battle.1 However, the Muslim forces eventually rallied under the Prophet's leadership and achieved a decisive victory.1 Khalid's participation, despite being wounded, further demonstrated his commitment to the Islamic cause.

III. Forging a Caliphate: The Ridda Wars (632-633)

A. Strategic Context

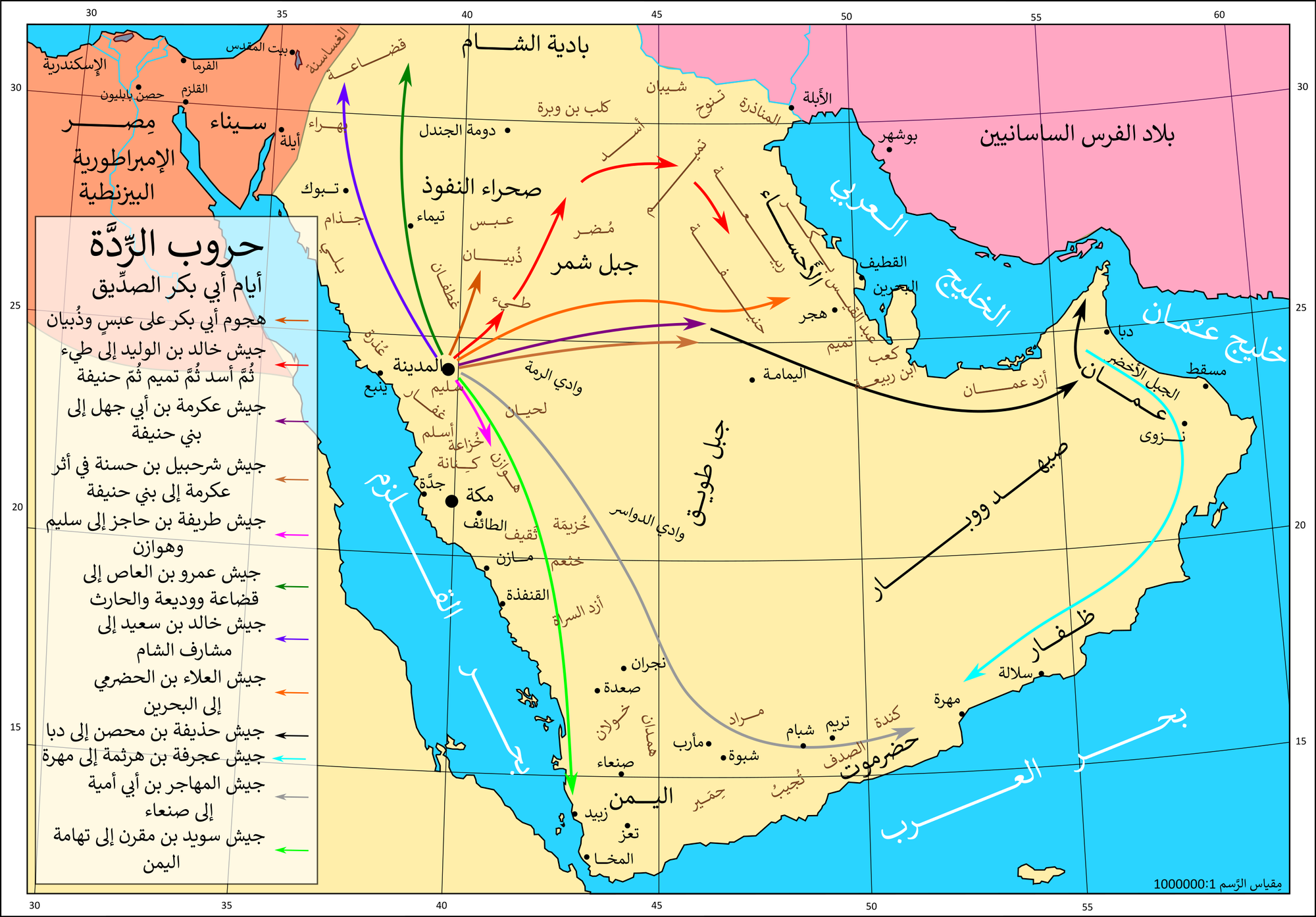

The death of Prophet Muhammad in June 632 CE precipitated a major crisis for the nascent Islamic state based in Medina. While Abu Bakr was elected as the first Caliph (successor), his authority was immediately challenged as numerous Arab tribes across the peninsula renounced their allegiance to Medina.7 This wave of rebellion, known as the Ridda (Apostasy) Wars, stemmed from various factors: a rejection of Medina's centralized political control, resentment towards the religious tax (Zakat), the resurgence of tribal particularism, and the emergence of rival figures claiming prophethood, such as Tulayha al-Asadi, Musaylima al-Kadhdhab ("the Liar") of the Banu Hanifa, Sajah bint al-Harith, and al-Aswad al-Ansi in Yemen.4

Caliph Abu Bakr adopted an uncompromising stance, viewing the rejection of Zakat as tantamount to abandoning Islam itself and a direct threat to the unity and survival of the Muslim community.24 He organized the Muslim forces into eleven distinct corps, each assigned a specific region or tribal group to subdue.24

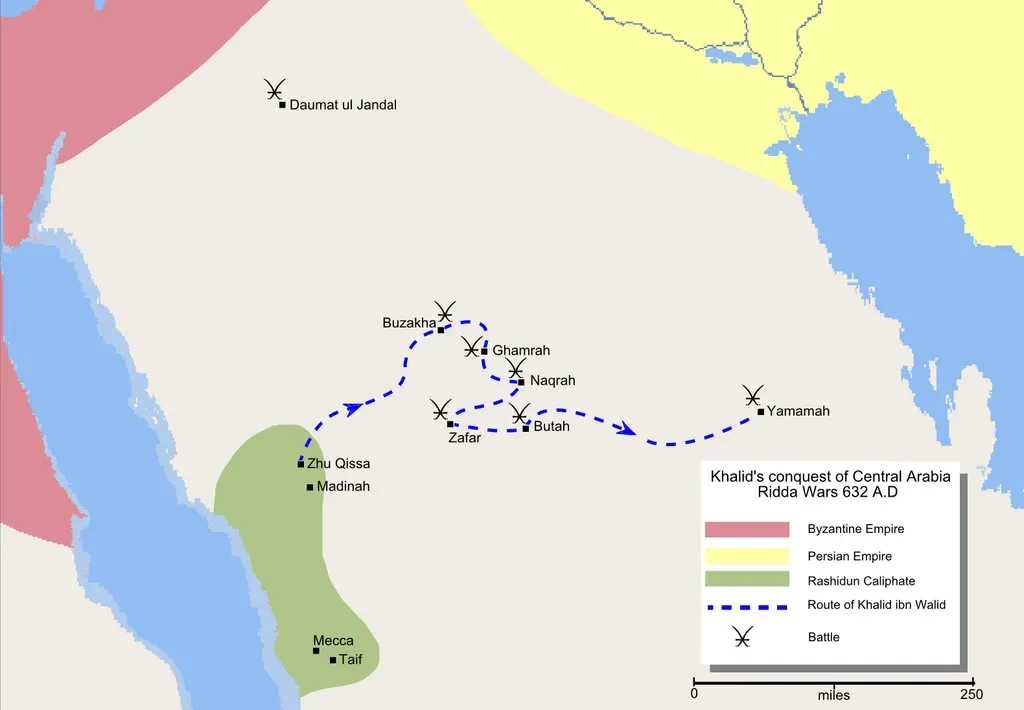

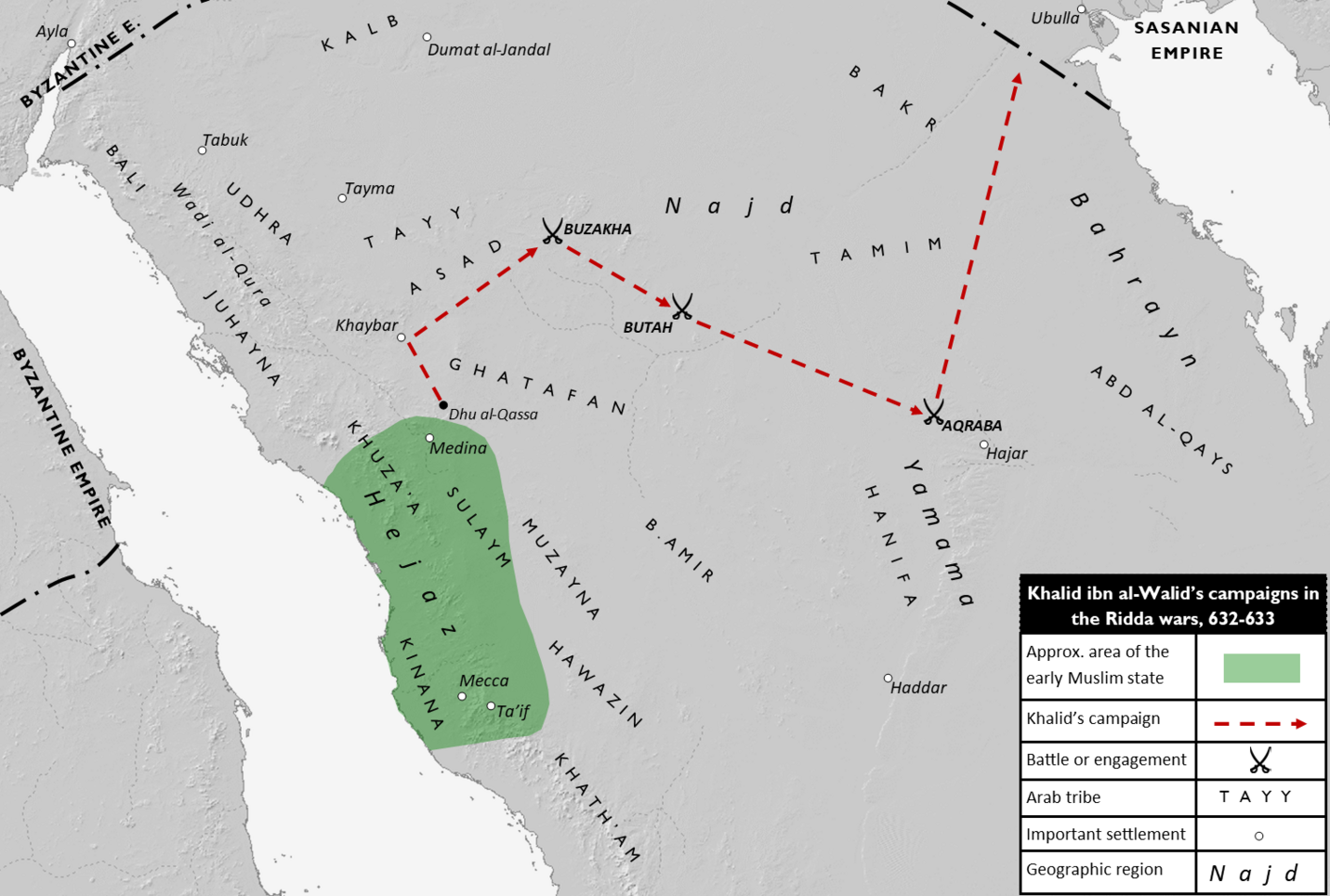

This strategy aimed to tackle the disparate rebellions simultaneously, preventing the tribes from uniting against Medina and allowing the Caliphate to maintain the initiative.10 Khalid ibn al-Walid was entrusted with command of the strongest corps and tasked with confronting the most formidable centers of resistance, particularly the forces rallied around the rival 'prophets' Tulayha and Musaylima.1

B. Campaign Against Tulayha (Banu Asad, Ghatafan, Tayy, Fazara)

Tulayha ibn Khuwaylid of the Banu Asad tribe was a prominent rival prophet who had gathered a significant following among the tribes of north-central Arabia, including the powerful Ghatafan and elements of the Tayy.1

- Battle of Buzakha (Late 632): Khalid's first major objective was to neutralize Tulayha's coalition, encamped near the well of Buzakha in Asad territory.1 Before engaging Tulayha directly, Khalid demonstrated astute political and military sense. Abu Bakr and Khalid leveraged the influence of Adi ibn Hatim, the respected chief of the Tayy tribe who remained loyal to Medina.1 Adi successfully mediated with his kinsmen, persuading the Tayy contingent (around 500 horsemen) to abandon Tulayha and join the Muslim forces.1 He also secured the submission of the allied Banu Jadila tribe (1,000 warriors).4 This diplomatic success significantly weakened Tulayha's army while simultaneously bolstering Khalid's ranks, which had initially numbered around 6,000.4At Buzakha, Khalid launched a direct assault against the remaining forces of the Asad and Ghatafan.1 The battle was fiercely contested.4 However, as the tide began to turn against the rebels, the Fazara section of the Ghatafan, led by their chief Uyayna ibn Hisn, lost heart and deserted the battlefield.1 This desertion proved decisive, compelling Tulayha to flee the field, reportedly escaping to Syria.1 Following their leader's flight, the Banu Asad submitted to Khalid, as did the previously neutral Banu Amir tribe, who had awaited the battle's outcome.1 Uyayna ibn Hisn was later captured and sent to Medina.1 The victory at Buzakha was crucial, breaking the back of the rebellion in Najd and bringing most of north-central Arabia under Muslim control.1 Key sources for this battle include Tabari, Baladhuri, Ibn Qutaiba, and modern analyses by Akram, Watt, Kennedy, and others.1

- Battle of Ghamra (Following Buzakha): Khalid pursued the remnants of Tulayha's defeated forces. A subsequent engagement took place at Ghamra, located about 20 miles from Buzakha.24 Here, Khalid defeated the remaining rebels, consolidating his victory.24 Some accounts mention Uyaina being captured after fleeing towards Ghamra.24

C. Campaign Against Banu Sulaim

Following the suppression of Tulayha's main force, Khalid turned his attention to other rebellious groups in the region.

- Battle of Naqra (October 632/633?): The Banu Sulaim tribe, under their chief Amr bin Abdul Uzza (also known as Abu Shajara), remained defiant.4 Khalid confronted them on the plain of Naqra.4 The Banu Sulaim offered stubborn resistance, but Khalid's experienced forces eventually prevailed.4 Abu Shajara was captured in the battle.4 Following this defeat, the Banu Sulaim submitted to Khalid's authority.4 Sources like Akram and Baladhuri document this engagement.4

D. Campaign Against Salma (Umm Ziml)

Another center of resistance emerged around a charismatic chieftainess.

- Battle of Zafar (October 632): Salma, also known as Umm Ziml, a respected chieftainess of the Ghatfan tribe, rallied remnants of defeated tribes (Ghatfan, Hawazin, Sulaim) at Zafar.4 She directed the battle from an armored litter atop a renowned camel, which became a rallying point for her fiercest warriors.4 Khalid recognized that Salma herself was the key to the enemy's morale and resistance. He led a determined assault by a picked group of warriors directly towards her camel.4 Despite fierce defense around the camel (reportedly 100 followers died defending her), Khalid's men reached it, brought it down, and killed Salma.4 With her death, the apostate resistance collapsed completely.4 Tabari is a key source for this battle, which marked the end of major resistance in North-Central Arabia.4

E. Campaign Against Banu Tamim & Malik ibn Nuwayra (Controversy)

Khalid's campaign then moved towards the territory of the Banu Tamim tribe. While some clans submitted, the actions surrounding Malik ibn Nuwayra, a chief of the Banu Yarbu' clan (part of Banu Tamim), became highly controversial.4 Malik had been appointed as a Zakat collector by Prophet Muhammad but had withheld the tax after the Prophet's death and reportedly allied himself with the false prophetess Sajah bint al-Harith.4

Khalid marched to al-Butah, the area associated with Malik's clan. Accounts of what transpired differ significantly in the early sources.12 Some report that Malik, perhaps realizing the futility of resistance, had advised his clansmen to disperse and make peace.4 When Khalid's troops arrived, they captured Malik and some of his companions. A dispute arose among the Muslim soldiers regarding whether Malik and his men had performed the Muslim prayer (Adhan/Salat), which would indicate their status as Muslims.19 Abu Qatadah al-Ansari, a prominent Companion, testified that they had prayed, while others disputed this.19

Amidst this ambiguity, Khalid ordered Malik's execution.4 The reasons cited or inferred include Malik's withholding of Zakat (which Abu Bakr considered apostasy), his alleged alliance with Sajah, his ambiguous statements ("Your companion [Muhammad] used to say that" regarding prayer/Zakat), or simply Khalid's misjudgment and haste.19 Compounding the controversy, Khalid married Malik's widow, Layla bint Sinan (renowned for her beauty), shortly after the execution, leading to accusations that he had killed Malik out of desire for his wife.4

The incident caused uproar. Malik's brother, Mutammim ibn Nuwayra, a respected poet, traveled to Medina to complain directly to Caliph Abu Bakr.19 Umar ibn al-Khattab vehemently condemned Khalid's actions, demanding his dismissal and punishment for killing a Muslim and unlawfully taking his wife.4 Abu Bakr summoned Khalid for questioning. While he reprimanded Khalid for his haste and potential misjudgment, he ultimately accepted Khalid's explanation (that he believed Malik an apostate) and refused to dismiss him, famously stating he would not sheathe a sword that Allah had unsheathed against the disbelievers.19 Abu Bakr did, however, pay the blood money (diyah) for Malik from the state treasury, acknowledging a degree of doubt or error in the killing.4 The Banu Tamim were subdued 29, but the incident left a lasting legacy of friction between Khalid and Umar, foreshadowing future events.4 The affair highlights the complex legal and political questions facing the early Caliphate regarding the definition of apostasy, the rules of engagement, and the accountability of military commanders. Key sources detailing this controversial episode include Tabari, Waqidi, Ibn Ishaq, Sayf ibn Umar, Ibn Sa'd, Khalifa ibn Khayyat, Baladhuri, and Ibn Kathir.4

F. Campaign Against Musaylima (Banu Hanifa)

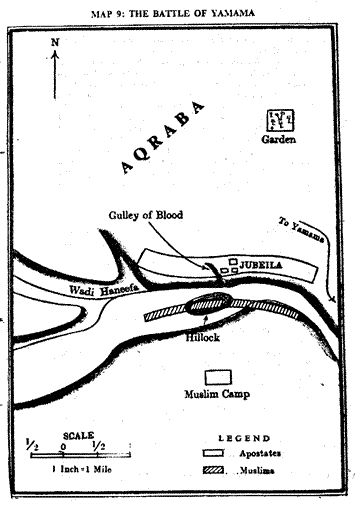

The most formidable challenge in the Ridda Wars came from Musaylima, the rival prophet who commanded a large following among the powerful Banu Hanifa tribe in the fertile region of Yamama in central Arabia.4 Musaylima had already defeated two Muslim armies sent against him under the commands of Ikrimah ibn Abi Jahl and Shurahbil ibn Hasana, who had attacked prematurely against Abu Bakr's orders.4 Khalid was dispatched with the main Muslim force to decisively crush this rebellion.10

- Battle of Yamama / Aqraba (December 632 / Early 633): Khalid concentrated his forces, incorporating the remnants of Shurahbil's corps and reinforcements from Medina, bringing his army to approximately 13,000 men.4 Musaylima's forces, drawn from the Banu Hanifa, were reportedly much larger, with traditional sources claiming 40,000 or more; while likely exaggerated, they certainly held numerical superiority.4 The two armies met on the plain of Aqraba.1The battle was exceptionally fierce and bloody, described as the hardest fought by the Muslims up to that point.4 The Banu Hanifa, fighting with fanatical devotion to Musaylima, initially pushed the Muslims back.4 Khalid had to reorganize his troops, reportedly mixing tribal contingents to improve cohesion.4 Prominent Muslims, including Zayd ibn al-Khattab (Umar's brother), fell in the intense fighting.30Gradually, the Muslims gained the upper hand, forcing Musaylima and his core followers (estimated around 7,000) to retreat into a large walled garden, which they fortified.4 The Muslims laid siege to the garden. In a famous act of bravery, al-Bara' ibn Malik asked his comrades to throw him over the wall; he managed to fight his way to the gate and open it for the Muslim army.30 The ensuing combat within the garden was a brutal slaughter, earning it the name Hadiqat al-Mawt (the Garden of Death).4The climax came with the death of Musaylima himself. He was reportedly struck down by a javelin thrown by Wahshi ibn Harb – the same man who had killed Hamza at Uhud – and possibly finished off by others.4 With their leader killed, the remaining Banu Hanifa resistance collapsed.4The Battle of Yamama was a decisive, albeit costly, victory for the Caliphate.4 It effectively ended the major organized resistance of the Ridda Wars.4 Muslim losses were heavy, around 1,200 martyrs, including a disproportionately high number of huffaz – Companions who had memorized the entire Quran.10 This significant loss of Quran memorizers deeply concerned Umar ibn al-Khattab, who persuaded Caliph Abu Bakr to undertake the first official compilation of the Quranic text to ensure its preservation.10 Thus, a direct consequence of Khalid's bloody victory at Yamama was a pivotal development in the history of the Islamic scripture. Sources include Tabari, Baladhuri, Akram, Ibn Kathir, and others.4

G. Summary Table: Khalid ibn al-Walid's Major Battles in the Ridda Wars

The Ridda Wars involved numerous campaigns across Arabia.1 The following table summarizes Khalid's key engagements during this critical period, providing a structured overview of his path through central and northern Arabia.

Note: The Malik ibn Nuwayra incident involved capture and execution rather than a pitched battle, and remains highly controversial.

H. Reflections on the Ridda Wars Campaign

Khalid's campaigns during the Ridda Wars were instrumental in preserving the unity of the nascent Islamic state under the authority of the Caliphate in Medina.10 His success stemmed from a potent combination of factors. Militarily, he displayed tactical brilliance (as seen at Buzakha and Yamama), decisiveness in targeting enemy leadership (Zafar), and an ability to adapt his forces, even integrating former opponents like the Tayy tribe.1 This military prowess was guided by the clear strategic objectives set by Caliph Abu Bakr, who provided crucial political backing and reinforcements.24 These campaigns were not merely military exercises; they were fundamentally about establishing the political and religious supremacy of the Medinan Caliphate throughout Arabia, enforcing the obligations of Islam (like Zakat), and eliminating rival claims to prophetic authority.10

However, the campaign also revealed underlying tensions. The controversy surrounding Malik ibn Nuwayra 4 brought to the fore critical questions about the rules of engagement, the precise definition of apostasy versus political dissent, and the degree of autonomy granted to field commanders. The stark contrast between Umar ibn al-Khattab's demand for Khalid's punishment and Abu Bakr's more pragmatic decision to retain his most successful general, while acknowledging a potential error by paying blood money, highlighted differing approaches to justice, governance, and military necessity within the highest echelons of Muslim leadership. This friction between Umar and Khalid, rooted in incidents like the Malik affair, would resurface later and contribute to Khalid's eventual dismissal by Umar when he became Caliph.4

IV. Challenging Empires: The Persian Campaign (Iraq, 633-634)

A. Invasion Strategy and Initial Moves

With the Arabian Peninsula largely pacified following the Ridda Wars, Caliph Abu Bakr sent a letter to Khalid, and scholars debate to this day whether it was an order to come home after successfully completing the objective of the Ridda Wars - or - encouragement to pursue expansionism, thereby initiating the great Islamic conquests. Bearing in mind the Malik's wife issue was still boiling and Umar's growing influence in the circles of power, it most probably was the former.

In any case, whatever the contents of the letter, Khalid pressed on. The first major target was the vast world superpower of the Sasanian Persian Empire to the northeast, beginning with its province of Iraq (Lower Mesopotamia).1 The timing was opportune; the Sasanian Empire, though still formidable and the strongest military force on the planet, was weakened by decades of exhausting warfare against the Byzantine Empire and plagued by internal political instability following the overthrow of Khosrau II.11

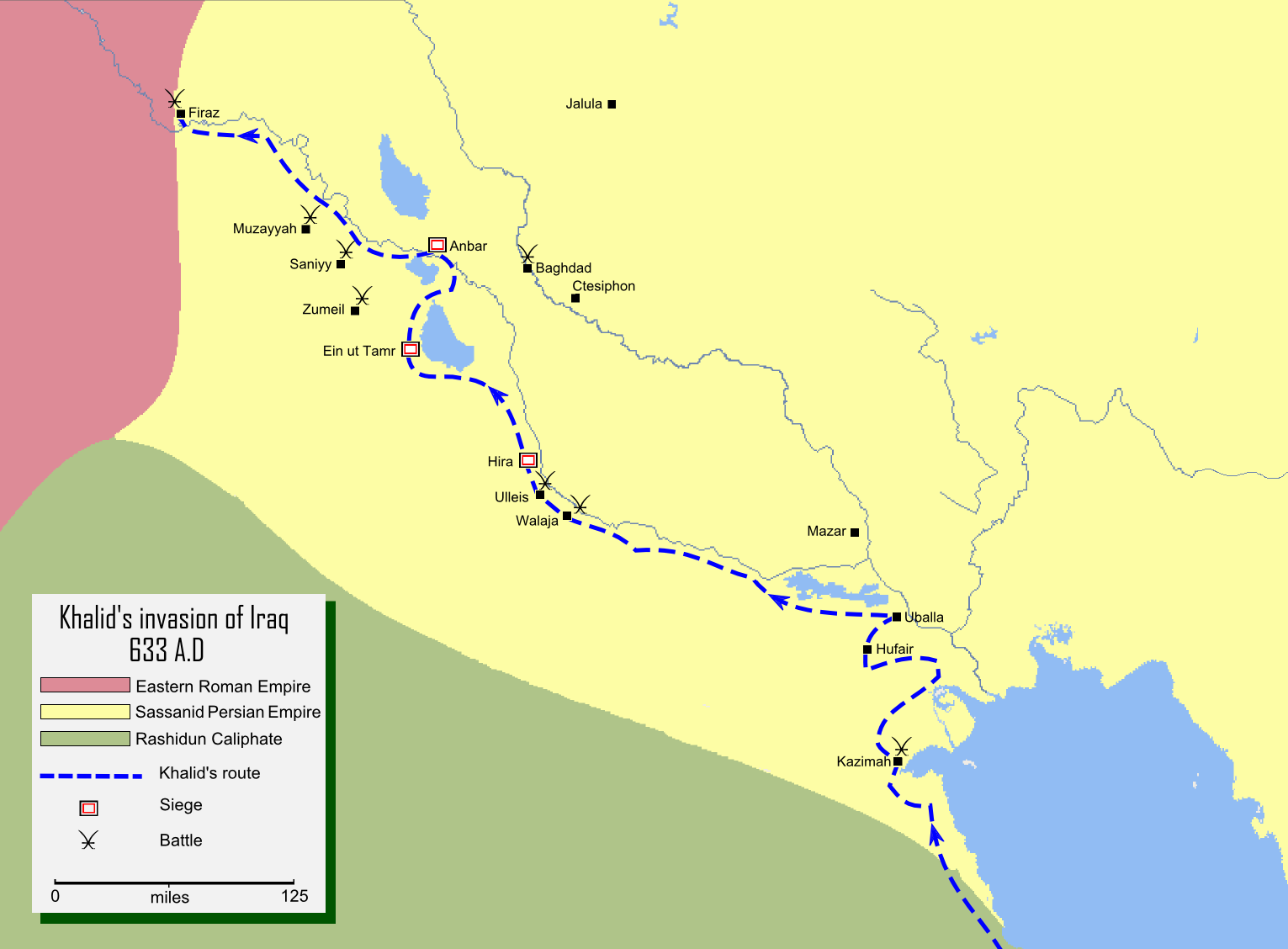

Khalid ibn al-Walid, fresh from his decisive victory at Yamama, decided to invade with himself personally leading the invasion. In the late spring or early summer of 633 CE, he marched north from Yamama towards the southern frontiers of Iraq.1 His initial core force was observed to have been relatively small, perhaps around 1,000 warriors, composed of nomadic Arabs and possibly remnants of the Medinan contingents (sources like Donner and Athamina debate the exact composition).1 However, his army was quickly grown by allied Arab tribesmen from the region, most notably the Banu Shayban led by the influential chief Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, as well as contingents from the Tamim, Tayy, and Asad tribes.1 This brought his total strength to a maximum paltry 18,000 men.4

Khalid's strategic objective was the capture of al-Hira, the major Sasanian administrative center for the middle Euphrates region.1 This central city would firmly establish the Islamic Empire across that entire region without having to destroy each of the surrounding provinces individually. His operational approach focused on advancing along the western bank of the Euphrates River, by far the best manned and defended path, systematically eliminating Sasanian border garrisons and defeating allied Arab tribes loyal to the Persians.1 While some early sources mention an initial attack on Ubulla (near modern Basra), the consensus, supported by historians like Tabari and Donner, suggests Ubulla was likely conquered later by a different commander, Utba ibn Ghazwan.1 Khalid's main thrust began further west.

B. Battle of Chains (Dhat al-Salasil) (April 633)

Khalid's first major confrontation in Iraq was against the Sasanian frontier forces commanded by Hormuz, the governor of the district.4 The battle took place at Kazima (in modern Kuwait).1 Khalid commanded approximately 18,000 Muslim Arabs 4, facing Hormuz's army of Persians and Arab auxiliaries, estimated between 15,000 and 40,000 men.31

Hormuz deployed his forces at Kazima, anticipating Khalid's approach. A notable feature of the Sasanian deployment was the use of chains linking soldiers together in units of three to ten men.1 This tactic aimed to demonstrate resolve and prevent breaches in their lines but severely hampered mobility.31 Khalid, anticipating Hormuz's position, employed a brilliant maneuver. He initially marched towards Hufair, away from Kazima, compelling the heavily laden, chain-linked Persian army to undertake an exhausting march to intercept him. Khalid then rapidly counter-marched back towards Kazima, arriving before the fatigued Persians could fully recover or redeploy effectively.4

The battle commenced with a duel between the commanders, in which Khalid swiftly killed Hormuz.4 The Muslim forces then launched a general assault. The tired Persian army, encumbered by their chains, could not withstand the onslaught for long. Their front broke, and the chains that were meant to ensure cohesion turned into fetters, preventing an orderly retreat. Thousands of chained Sasanian soldiers were slaughtered.4 The Battle of Chains was a decisive Muslim victory, marking the first major defeat of a Sasanian army by the Caliphate in Iraq and demonstrating Khalid's tactical ingenuity in exploiting enemy weaknesses.1 Key sources include Tabari, Akram, Pourshariati, and Howard-Johnston.4

C. Battle of the River (Nahr al-Mar'a / Madhar) (April 633)

Following the disaster at Chains, Sasanian reinforcements arrived under the command of Qarin bin Qaryanz. These forces, joined by survivors from Chains (including wing commanders Qubaz and Anushjan), prepared to confront Khalid.1 The engagement, known as the Battle of the River or Battle of Madhar, took place near the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates, possibly at the site of modern Azeir.1

The battle began dramatically with challenges for single combat. The three main Sasanian commanders – Qarin, Qubaz, and Anushjan – were all killed in duels by Muslim champions (Maqal bin Al Ashi, Asim bin Amr, and Adi bin Hatim, respectively) before the general engagement even began.32 Deprived of their leadership, the Sasanian army fought bravely but was ultimately routed by Khalid's general assault.32 Reports, particularly from Tabari, claim exceptionally heavy Persian losses, with figures as high as 30,000 killed, though these numbers are likely exaggerated.4 The victory yielded significant spoils for the Muslims.4 Primary sources include Tabari, Akram, and Morony.4

D. Battle of Walaja (May 633)

The Sasanian response escalated. A new army was assembled under the command of Andarzaghar, reinforced by Christian Arab allies and survivors from previous defeats.4 Another senior commander, Bahman Jadhuyih, was en route with a separate army but had not yet joined Andarzaghar.4 Khalid intercepted Andarzaghar's force, estimated at 15,000-30,000, with his own army of approximately 15,000 at Walaja, a plain between two low ridges.1

At Walaja, Khalid executed one of his most celebrated tactical maneuvers, a variation of the double envelopment reminiscent of Hannibal's masterpiece at Cannae.33 During the night before the battle, he dispatched two strong cavalry detachments (around 2,000 men each, led by Busr bin Abi Rahm and Saeed bin Marra) on a wide flanking march to conceal themselves behind the ridge to the Persian rear.4

The next day, Khalid engaged the Persians frontally with his main force. As the fierce battle progressed, possibly involving a feigned withdrawal by the Muslim center to draw the Persians forward 33, Khalid gave the pre-arranged signal. The hidden cavalry squadrons charged unexpectedly from the rear and flanks, while the main Muslim line renewed its attack from the front.4 Caught in this perfectly timed pincer movement, the Sasanian army was thrown into chaos, completely surrounded, and annihilated.4 Sasanian losses were reported to be around 20,000.33 Andarzaghar himself escaped the encirclement only to perish from thirst in the desert later.4 Walaja is considered a prime example of Khalid's tactical genius and operational planning.8 Sources include Tabari, Akram, Crawford, Blankinship, Morony, Muir, and others.4

E. Battle of Ullais (River of Blood) (May 633)

The string of defeats enraged the Persians and their Christian Arab allies. A large force, composed of Sasanian troops under a new general, Jaban, and numerous Christian Arab tribesmen (particularly the Bani Bakr seeking revenge for Walaja) led by Abdul-Aswad Ajli, gathered at Ullais on the Euphrates to block Khalid's path to Hira.4 This combined army significantly outnumbered Khalid's forces.4

The ensuing battle was exceptionally hard-fought and prolonged.4 Khalid personally slew the Arab commander Abdul-Aswad in combat.4 According to accounts primarily from Tabari and Ibn Kathir, during the intense struggle, Khalid made a vow to Allah that if granted victory, he would make a river flow with the enemy's blood.4 After the Muslims finally broke the enemy resistance, Khalid allegedly ordered the mass execution of thousands of captured Persian and Arab soldiers over several days, having them beheaded by the river until, according to legend, the water ran red, fulfilling his vow and giving the battle its grim moniker, "River of Blood".4

This episode, particularly the vow and the scale of the executions, is highly controversial. While reported by influential historians like Tabari, other early sources like al-Baladhuri are silent on the matter or offer different interpretations, and some modern historians view the "River of Blood" story as legendary embellishment, possibly conflated with actions of other commanders.21 Regardless of the veracity of the vow story, the battle resulted in another decisive Muslim victory and devastating casualties for the Sasanian-Arab coalition, with traditional sources claiming up to 70,000 enemy dead.4 Jaban, the Persian commander, escaped.4 Sources include Tabari, Ibn Kathir, Akram, Baladhuri, Crawford, Nafziger/Walton, and the Cambridge History of Iran.4

F. Conquest of al-Hira (May 633?)

With the main Sasanian field armies defeated, Khalid advanced on his primary objective: al-Hira. This ancient city, the former capital of the Lakhmid Arab kings, now served as the Sasanian administrative center for the region and had a large Arab Christian population.1 Khalid employed a strategic approach, bypassing the city initially and appearing from the rear via the town of Khawarnaq.4 The Sasanian governor, Azazbeh, had initially intended to defend the city but lost his resolve after hearing of the death of the Sasanian Emperor Ardsheer and the defeat of a cavalry detachment led by his own son. Azazbeh withdrew his garrison across the Euphrates towards the Sasanian capital, Ctesiphon, leaving Hira undefended.4

While the city itself was unwalled, its Arab Christian nobles and their retainers barricaded themselves within four heavily fortified palaces or citadels scattered throughout the city.1 Khalid systematically besieged each citadel. The leaders – Iyas bin Qubaisa, Adi bin Adi, Ibn Akal, and the elderly Abdul Masih bin Amr bin Buqaila – eventually negotiated terms of surrender.4 Khalid personally conducted the final negotiations with Abdul Masih.4

Hira surrendered peacefully.1 Under the terms of the agreement, the inhabitants were granted protection for their lives, property, churches, and palaces in exchange for paying the Jizya (poll tax).1 The amount is sometimes cited as 190,000 dirhams.34 The capture of Hira was a major strategic success, providing Khalid with a secure base for further operations in Iraq and consolidating Muslim control over the middle Euphrates.4 Key sources are Tabari, Baladhuri, Khalifa ibn Khayyat, and Akram.1

G. Siege of Anbar (Dhat al-Uyun) (633)

Following the capture of Hira, Khalid continued his campaign northwards along the Euphrates. He laid siege to the strongly fortified city of Anbar (ancient Peroz-Shapur).1 The Sasanian garrison, commanded by Shirzad, defended the city behind strong walls and a protective ditch.25

Khalid employed a distinctive and brutal tactic. He commanded his contingent of skilled archers to concentrate their fire specifically on the eyes of the Persian defenders lining the walls.4 This targeted archery proved devastatingly effective, blinding numerous defenders and severely undermining the garrison's morale and ability to resist. The siege subsequently became known as Dhat al-Uyun – the "Action (or Battle) of the Eye".4 Faced with this relentless and demoralizing assault, the Persian governor Shirzad soon negotiated terms of surrender. Khalid allowed Shirzad and his chosen retinue to depart peacefully with their personal belongings.4 Sources include Akram, Muir, and Ibn Kathir.4

H. Battle of Ayn al-Tamr (633)

Continuing his sweep west of the Euphrates, Khalid marched towards the oasis of Ayn al-Tamr.1 The oasis was defended by a Sasanian garrison within a fortress, commanded by Mihran Bahram-i Chubin, and a large force of allied Christian Arab tribes encamped outside the fort under the leadership of Aqqa ibn Qays ibn Bashir.1

Khalid first engaged the Arab tribal forces outside the fortress. In a swift action, possibly involving a direct charge or duel initiated by Khalid himself, the Arab commander Aqqa was captured.4 Aqqa was subsequently executed by Khalid, despite pleading for his life.4 With their allies defeated and leader captured, the Persian garrison under Mihran retreated into the fortress. Khalid laid siege, reportedly parading the captured Arabs and threatening executions, compelling the garrison to surrender.23 According to some accounts, the defeated Arab army and the Persian garrison were executed after the fall of the town.23

A notable discovery following the battle was the capture of forty Christian Arab youths found studying the Gospels in a monastery or church within the oasis.4 These youths were taken captive to Medina. Remarkably, several of them or their descendants became prominent figures in Islamic history, including Nusayr (father of Musa bin Nusayr, the conqueror of Spain), Sirin (father of the famous dream interpreter Muhammad ibn Sirin), and Yassar (grandfather of Ibn Ishaq, the Prophet's first major biographer).23 This incident provides a fascinating glimpse into the cultural encounters and assimilation processes occurring alongside the military conquests. Sources include Tabari, Akram, Ibn Atheer, Muir, Morony, Baladhuri, and Ibn Kathir.4

I. Consolidation Campaigns

After securing Ayn al-Tamr, Khalid undertook further campaigns to consolidate Muslim control over the western desert fringes and suppress remaining pockets of resistance.

- Second Battle of Dawmat al-Jandal (August 633): Dawmat al-Jandal, a strategic oasis in northern Arabia, had been captured earlier but subsequently saw renewed resistance from local Christian Arab tribes, primarily the powerful Banu Kalb, possibly joined by elements of the Ghassanids and Tanukhids, under leaders like Judie ibn Rabeea and perhaps the previously subdued Ukaidir ibn Abd al-Malik.1 Another Muslim commander, Iyad ibn Ghanm, had been dispatched by Abu Bakr to retake the oasis but found himself bogged down in a siege and requested Khalid's assistance.1Khalid made a rapid march from Iraq with around 6,000 men, joining Iyad and taking overall command.4 He blockaded the fortress. When the defenders under Judie sallied out, Khalid decisively defeated them, capturing Judie and many of his clansmen.35 In a grim display intended to break the remaining defenders' will, Khalid had Judie and the other captives publicly beheaded in front of the fortress walls.4 This act, however, reportedly hardened the resolve of those inside. After several more days, Khalid's experienced troops stormed the fortress, overcoming fierce resistance. The garrison was largely slaughtered, and numerous captives were taken.4 This victory secured a crucial strategic point controlling routes between Syria, Iraq, and Arabia. Sources include Tabari, Akram, Vaglieri, and Shahid.4

- Battles of Muzayyah, Saniyy, and Zumail (November 633?): Following his return from Dawmat al-Jandal, Khalid launched a sophisticated operation to eliminate scattered Sasanian and allied Arab forces still operating west of the Euphrates. These included Persians under Mahbuzan and Arabs under Huzail bin Imran concentrated at Muzayyah, and other Arab groups at Saniyy (under Rabi'a bin Bujair) and Zumail.4Khalid employed a daring and complex tactic: simultaneous, converging night attacks on each location.4 He divided his army into three corps, which marched from different locations (Husaid, Khanafis, Ain-ut-Tamr) along separate routes, coordinating their arrival and attack on Muzayyah for a specific pre-dawn hour.4 This perfectly executed surprise attack overwhelmed the enemy camp, inflicting heavy casualties, though Huzail escaped.4 Khalid repeated this three-pronged night attack strategy successfully against the Arab camp at Saniyy, where the commander Rabi'a bin Bujair was killed, and again a few nights later at Zumail, effectively annihilating these remaining pockets of resistance.4 The precise locations of these battles are debated, but they likely occurred in the desert region west of the Euphrates.4 This series of coordinated raids demonstrated exceptional planning, discipline, and command and control. Tabari and Akram are key sources.4

J. Battle of Firaz (January 634)

Khalid's final battle during his Iraqi campaign occurred at Firaz, a frontier post located at the edge of the Sasanian and Byzantine empires.1 Here, he encountered a coalition force comprising local Sasanian and Byzantine garrisons, along with allied Christian Arab tribes, who had temporarily united against the common Muslim threat.4

After a period of standoff across the Euphrates River, Khalid reportedly goaded the coalition forces into crossing the river to attack him on his chosen ground.4 Once they had crossed, he launched a fierce counter-attack, trapping them with the river at their backs and employing flanking maneuvers similar to those used at the Battle of the River (Madhar).36

According to traditional Islamic sources, the battle resulted in a resounding Muslim victory with enormous coalition casualties (figures like 100,000 are mentioned but are considered highly improbable).1 However, the scale and even the significance of this battle are questioned by some modern historians. The number of troops involved was likely much smaller than traditional accounts suggest, and the extent of Byzantine participation may have been limited.36 Some scholars, like Takirtakoglou, propose the event might have been exaggerated or misrepresented in the sources.36 Nevertheless, in the traditional narrative, Firaz marks the culmination of Khalid's extraordinarily successful first phase of the conquest of Iraq.4 Sources include Tabari, Akram, Muir, Crawford, Morony, Kaegi, Pourshariati, Bennett, and Takirtakoglou.4

K. Summary Table: Khalid ibn al-Walid's Major Battles in the Persian Campaign (Iraq)

Khalid's campaign in Iraq was characterized by a rapid sequence of engagements against Sasanian forces and their allies.1 The following table summarizes the key battles and sieges of this phase.

L. Reflections on the Persian Campaign

Khalid's campaign in Iraq stands as a remarkable example of successful maneuver warfare against a seemingly superior opponent. His generalship displayed a mastery of diverse military skills. He utilized combined arms effectively, coordinating infantry and his highly mobile cavalry, and potentially even river transport for logistics.4 He understood the value of psychological warfare, using challenges to single combat to eliminate enemy leaders and demoralize their troops 4, and employing tactics designed to instill fear, such as the blinding arrow volleys at Anbar 4 or the controversial executions at Ullais and Dawmat al-Jandal.4 Most significantly, his campaigns were characterized by speed, surprise, and sophisticated maneuvers like the feint before Chains 4, the double envelopment at Walaja 4, and the coordinated night convergences at Muzayyah, Saniyy, and Zumail.4 These tactics consistently allowed him to achieve local superiority and decisive results despite often facing numerically larger forces, demonstrating a grasp of principles aligning with modern concepts of operational art.27

Conversely, the Sasanian response appears reactive and poorly coordinated. They consistently underestimated the speed and capability of the Muslim forces and failed to concentrate their own armies effectively. Sending commanders like Hormuz, Qarin, Andarzaghar, and Jaban sequentially allowed Khalid to engage and defeat them in detail before they could unite their full strength.4 The Sasanian reliance on heavy infantry, static defenses like the chains at Kazima 4, and fortified positions proved largely ineffective against Khalid's fluid, offensive-oriented approach.4 This suggests a strategic failure on the part of the Sasanian leadership to adapt to the novel threat posed by the highly mobile and motivated Arab Muslim armies under Khalid's command.

V. The Conquest of Syria (Levant, 634-638)

A. The Audacious Desert March (June 634)

In early 634, while Khalid was concluding his campaign in Iraq, the Muslim armies dispatched earlier by Caliph Abu Bakr to invade Byzantine Syria were facing stiff resistance and appeared insufficient for the task.39 The commanders in Syria requested reinforcements.39 Responding to the urgency, Abu Bakr made a bold strategic decision: he ordered Khalid ibn al-Walid to immediately proceed from Iraq to Syria, take overall command of the Muslim forces there, and lead the invasion.1 Speed was paramount.57

Faced with this order, Khalid had to choose a route. The conventional options – south via Daumat al-Jandal or north along the Euphrates – were deemed too slow or too exposed to Byzantine garrisons who would surely try to intercept him.57 Instead, Khalid opted for an extraordinary and highly perilous route: a direct march across the largely trackless and waterless Syrian Desert (Badiyat ash-Sham, also referred to as Samawa).1 This route, stretching from Quraqir in western Iraq towards Suwa near Palmyra in Syria, involved a five-day crossing of approximately 120 miles without any reliable water sources.57 Such a journey was considered suicidal even for lone travelers, let alone an army of around 9,000 men.57

To accomplish this unprecedented feat, Khalid relied on the expertise of a local guide, Raafe bin Umaira, and employed innovative logistical solutions.57 The most critical challenge was water. Reportedly, Khalid had a number of camels drink excessive amounts of water and then sealed their mouths. Each day, a certain number of these camels were slaughtered, and the water stored in their stomachs was extracted for the soldiers and horses.57

In early June 634, Khalid and his army plunged into the desert. After five grueling days, they emerged, exhausted but successful, near Suwa in Syria, completely bypassing Byzantine frontier defenses and appearing where least expected.1 This audacious march is considered one of Khalid's most brilliant strategic maneuvers. It demonstrated exceptional leadership, boldness, meticulous planning, and logistical ingenuity. Its success stunned the Byzantines, allowed the scattered Muslim armies in Syria to concentrate under a unified and highly capable command, and seized the strategic initiative for the Caliphate.1

The march significantly boosted Khalid's already formidable reputation.1 Key sources include Tabari and Akram.57

B. Opening Engagements

Upon arriving in Syria, Khalid immediately took action against Byzantine allies and outposts.

- Battle of Marj Rahit (Ghassanid Camp) (April/June 634?): Emerging from the desert, Khalid's first target appears to have been a large encampment of Ghassanid Arabs – Byzantine allies – gathered at Marj Rahit, east of Damascus, reportedly celebrating the Easter festival.1 Khalid launched a surprise raid on the camp, routing the Ghassanids and capturing significant spoils. This swift action announced his dramatic arrival in Syria and served notice to the Byzantines and their allies. (Note: The date April 24, 634 often associated with this event seems inconsistent with Khalid's desert march timeline in June 634; it might refer to an earlier Ghassanid gathering or a conflation of events. The engagement was likely a raid rather than a major pitched battle.) Sources include early Islamic histories, though details in provided snippets are sparse.1

- Siege of Bosra (June-July 634): Khalid then moved south to link up with the other Muslim corps. He found Shurahbil ibn Hasana besieging Bosra, the former capital of the Ghassanids and a key strategic city.1 Khalid assumed command, bringing his elite mobile guard cavalry.60 The combined Muslim forces intensified the siege. Faced with Khalid's arrival and renewed pressure, the city surrendered in mid-July 634.1 The fall of Bosra effectively marked the end of the Ghassanid dynasty's power and secured a vital base for the Muslims in southern Syria.38

C. Battle of Ajnadayn (July 30, 634)

The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, realizing the seriousness of the invasion, ordered the concentration of available forces to confront the Muslims. The first major pitched battle occurred at Ajnadayn, a location generally placed near Bayt Jibrin in Palestine.1 All four main Muslim corps, now operating under Khalid ibn al-Walid's supreme command, converged to meet the Byzantine army.4 Muslim strength is estimated around 20,000 or more.4 The Byzantine army, likely commanded by Heraclius' brother Theodore Trithyrius (though sources also mention a "Wardan"), was numerically superior, with estimates ranging widely from 20,000 to over 90,000.4

The battle was fiercely contested. Early Byzantine tactics involved using archers and slingers to inflict casualties from a distance.4 Muslim champions, notably the fierce Dhiraar ibn al-Azwar, engaged Byzantine counterparts in single combat.4 A Byzantine plot to ambush Khalid during supposed peace talks was reportedly foiled.4 The main engagement saw heavy fighting across the front. Khalid skillfully managed his forces, possibly using reserves to counter Byzantine pressure points.

The outcome was a decisive victory for the Rashidun Caliphate.1 The Byzantine army suffered a crushing defeat and was forced to retreat northwards towards Damascus.37 Muslim casualties were also significant, with several prominent Companions of the Prophet martyred.37 Ajnadayn was a pivotal victory; it shattered the main Byzantine field army in southern Syria/Palestine and opened the region to further Muslim conquest.37 Sources include Waqidi, Tabari, Baladhuri, the Chronicle of Fredegar, and numerous modern historians.4

D. Battle of Fahl (Pella / Battle of the Marshes) (January 635)

Following the victory at Ajnadayn and the subsequent capture of Damascus (see below), Muslim forces pursued the remnants of the Byzantine army, who had regrouped in the Jordan Valley around the towns of Fahl (ancient Pella) and Beisan (ancient Scythopolis).1 Muslim commanders involved included Abu Ubaidah, Khalid, Shurahbil, and Amr ibn al-As, though accounts vary on the precise command structure for this specific battle.1 The Byzantine commander is named in Muslim sources as Saqlar ibn Mikhraq, likely identifiable as Theodore the Sacellarius.4

A key feature of this engagement was the Byzantine tactic of deliberately flooding the plains around Beisan by breaking irrigation dykes, hoping to impede the mobility of the Muslim cavalry.4 This turned the area into a marshland, giving the battle its alternative name, "Battle of the Marshes." Despite this obstacle, the Muslim forces managed to navigate the difficult terrain and engage the Byzantines.4 Some accounts describe a surprise Byzantine sortie from Beisan being repulsed with heavy losses, including the death of Saqlar.26

The battle resulted in another decisive Muslim victory.1 Byzantine casualties were reportedly very high (figures up to 10,000 or more are mentioned).4 Following the battle, Pella was captured, and Beisan and nearby Tiberias soon capitulated.26 This victory further weakened Byzantine defenses in the southern Levant.26 Sources include Balazuri, Ibn Ishaq, Al-Waqidi, Al-Yaqubi, Sayf ibn Umar, Ibn A'tham al-Kufi, Kennedy, Donner, and Burns.4

E. Siege of Damascus (August-September 634)

After the victory at Ajnadayn, Khalid marched his forces north towards Damascus, a major administrative, military, and economic center of Byzantine Syria.1 The siege began around August 21, 634.4 During the siege, news arrived of Caliph Abu Bakr's death (August 22) and the succession of Umar ibn al-Khattab. One of Umar's first acts was to appoint Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah as the overall commander-in-chief in Syria, replacing Khalid.4 Abu Ubaidah, out of respect or pragmatism, initially kept the order secret and allowed Khalid to continue directing the siege.4

The Byzantine garrison, commanded by Thomas (reportedly Emperor Heraclius' son-in-law), put up a determined defense.4 Khalid established a tight blockade, positioning detachments to cover the city gates and intercept relief forces.4 A significant Byzantine relief army (estimated at 12,000) sent by Heraclius from Emesa was intercepted and decisively defeated by Khalid at the Battle of Uqab Pass (Eagle Pass), about 20 miles north of Damascus.4

As the siege dragged on for about a month and the relief attempt failed, conditions inside the city deteriorated.4 The decisive moment came through betrayal. A Greek Orthodox priest or citizen named Jonah, possibly motivated by personal reasons or seeking favorable terms, contacted Khalid.4 He revealed that security would be lax at the East Gate during a night festival. Khalid seized the opportunity, leading a small, elite group (including notable warriors like Qa'qa ibn Amr) who scaled the wall using ropes provided by Jonah, overpowered the guards, opened the gate, and stormed into the city.4

Simultaneously, as Khalid's forces fought their way in from the east, the desperate city leaders, led by Thomas, negotiated a peaceful surrender with Abu Ubaidah, who was stationed at the opposite (Jabiyah) gate.4 Abu Ubaidah, known for his piety and preference for avoiding bloodshed, accepted the surrender and entered the city peacefully.4

The two Muslim commanders, Khalid and Abu Ubaidah, met inside the city, likely near the main church. A dispute arose over the status of the city: Khalid argued it was taken by force ('unwatan), implying the right to spoils and enslavement, while Abu Ubaidah insisted his peaceful treaty (sulhan) must be honored.4 Ultimately, Abu Ubaidah's authority as the newly (though perhaps not yet publicly announced) appointed commander-in-chief prevailed, and the terms of the peaceful surrender were applied to the entire city.4 These terms guaranteed safety for the inhabitants, their property, and their churches in exchange for payment of the Jizya. Departing Byzantine soldiers and citizens were given a three-day truce to leave safely.4 True to his aggressive nature, Khalid pursued the fleeing Byzantine refugees after the three-day truce expired and attacked their convoy near Antioch, inflicting further losses.58 The capture of Damascus on September 19 or 20, 634, was a major strategic and symbolic victory for the Muslims.1 Key sources include Waqidi, Tabari, Baladhuri, Akram, Nicolle, and Gibbon.4

F. Battle of Yarmouk (August 15-20, 636)

The Battle of Yarmouk represents the culmination of the initial phase of the Syrian conquest and arguably Khalid ibn al-Walid's greatest military achievement. Emperor Heraclius, determined to recover Syria, mobilized the full might of the Eastern Roman Empire.4 He assembled a massive, multi-ethnic army composed of Byzantine regulars (including elite cataphracts), Armenians, Slavs, Ghassanid Arabs, and other auxiliaries, concentrating them in northern Syria.4 Estimates of the Byzantine strength vary enormously, ranging from 50,000 to over 150,000, but all sources agree they vastly outnumbered the Muslims.4 The supreme command was given to the Armenian general Vahan, with other prominent commanders including Theodore Trithyrius (the Sacellarius), the Ghassanid king Jabalah ibn al-Aiham, Gregory, Dairjan, and Qanatir.4

Faced with this overwhelming concentration of force, the Muslim armies, then dispersed across Syria and Palestine, were in grave danger of being defeated piecemeal. Khalid ibn al-Walid, though formally subordinate to Abu Ubaidah, recognized the strategic imperative. He strongly advocated for a tactical withdrawal from captured cities like Emesa and Damascus and a concentration of all Muslim forces into a single army at a strong defensive position.4 Abu Ubaidah concurred. The Muslims retreated southwards, eventually choosing the plains near the Yarmouk River, a tributary of the Jordan River, southeast of the Sea of Galilee, as their battleground.4 This location offered secure flanks protected by deep ravines (Wadi-ur-Raqqad) and proximity to the Arabian desert for potential retreat. The total Muslim strength gathered at Yarmouk is estimated between 25,000 and 40,000.4 Recognizing Khalid's unparalleled military experience, Abu Ubaidah ceded effective field command to him for the duration of the battle.4

Khalid meticulously organized the Muslim army, deploying it in a strong defensive formation (Tabi'a) across a wide front (approx. 12 km) facing west.39 He divided the army into center (under Abu Ubaidah and Shurahbil), right wing (Amr ibn al-As), and left wing (Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan), each with cavalry reserves.39 Crucially, he kept his elite cavalry unit, the Mobile Guard (Tulay'a Mutaharrika), numbering around 4,000, under his personal command as a central reserve.39

The battle raged for six consecutive days from August 15th to 20th, 636.4

- Days 1-2: The Byzantines launched probing attacks, primarily against the Muslim wings. These were repulsed, often requiring the intervention of Khalid's Mobile Guard to stabilize the lines and launch flanking counter-attacks. Muslim women in the camps famously played a role in shaming and driving back any men who attempted to retreat.4

- Day 3: Vahan launched a major coordinated assault, particularly targeting the Muslim right wing under Amr ibn al-As. The Byzantine and Ghassanid forces achieved a significant breakthrough, pushing the Muslims back towards their camp. Khalid responded with a multi-pronged counter-attack, using his reserve and coordinating with other commanders, eventually repulsing the assault after hours of desperate fighting.4

- Day 4 ("Day of Lost Eyes"): The Byzantines shifted tactics, unleashing a massive barrage of archery against the Muslim left-center and left wing. This caused heavy casualties among the Muslims, with hundreds reportedly losing eyes, hence the day's grim name. The affected Muslim units were forced to fall back temporarily.4

- Day 5: A relative lull occurred as the Byzantines seemed hesitant after failing to break the Muslim lines. Khalid, sensing a shift in morale, used this day to prepare a decisive offensive for the following day.39

- Day 6: Khalid seized the initiative. Under cover of morning mist or a dust storm, he launched a coordinated attack. His masterstroke involved maneuvering the bulk of the Muslim cavalry, including the Mobile Guard, in a wide flanking movement to attack and drive the Byzantine cavalry completely off the battlefield.4 With their cavalry protection gone, the massive Byzantine infantry formations were exposed and vulnerable. Khalid's forces then attacked from the front and flanks. Simultaneously, Muslim detachments secured the key escape route across the Wadi-ur-Raqqad bridge.39 Panic ensued in the Byzantine ranks. The army collapsed into a disorganized rout, attempting to flee towards the deep ravines, where they were trapped between the Muslim attackers and the precipices. Tens of thousands were killed in the fighting or fell to their deaths in the ravines.4

The Battle of Yarmouk was a catastrophic and irreversible defeat for the Byzantine Empire.1 It effectively annihilated their main field army in Syria and permanently ended Byzantine rule over the Levant after nearly seven centuries.4 The battle is considered one of the most decisive in military history 39, cementing Khalid ibn al-Walid's reputation as one of the greatest tacticians and cavalry commanders of all time.4 It opened the entirety of Syria and Palestine to Muslim conquest.2 Numerous primary and secondary sources document this pivotal battle, including Waqidi, Tabari, Baladhuri, Theophanes, Pseudo-Dionysius, Akram, Nicolle, Kaegi, and Kennedy.4

G. Northern Campaigns (Post-Yarmouk)

Following the shattering victory at Yarmouk, the remaining Byzantine resistance in Syria was largely confined to fortified cities and northern garrisons. The Muslim armies, under the overall command of Abu Ubaidah but often with Khalid leading key operations, proceeded to systematically capture these remaining strongholds.

- Siege of Jerusalem (November 636 - April 637): While Abu Ubaidah consolidated control elsewhere, Amr ibn al-As likely continued operations in Palestine. After Yarmouk, Abu Ubaidah marched towards Jerusalem, with Khalid commanding the advance guard.4 The city, defended by its Byzantine garrison and led by the Patriarch Sophronius, withstood a siege for four to six months.4 Sophronius famously refused to surrender to anyone except the Caliph himself.4 An attempt to pass Khalid off as Caliph Umar failed due to Khalid's recognizability.4 Consequently, Caliph Umar traveled from Medina to Jabiya and then possibly to Jerusalem itself. The city surrendered peacefully to Umar in April 637. Khalid ibn al-Walid was present during Umar's visit to the region and served as one of the witnesses to the famous Pact of Umar, which guaranteed the safety and religious freedom of Jerusalem's inhabitants.4 Sources include Waqidi, Isfahani, and Akram.4

- Siege of Emesa (Homs) (Late 637?): Accounts vary on the exact timing, placing the main siege either before Yarmouk or, more likely, after the consolidation following Yarmouk and Jerusalem. Abu Ubaidah marched north with Khalid leading the vanguard.4 The city, commanded by Harbees, initially resisted.4 Khalid reportedly employed a clever tactic: feigning a withdrawal due to the onset of winter. When the Roman garrison under Harbees sallied out in pursuit, Khalid ambushed them with his main force, trapping and destroying the pursuing Romans. Khalid himself is said to have killed the Roman general in single combat. Following this disaster, the disheartened city negotiated a peaceful surrender, likely in late 637 or early 638.1 Sources include Ibn Kathir and Waqidi.4

- Siege of Aleppo (c. 637): Continuing north, the Muslim army under Abu Ubaidah and Khalid besieged the strongly fortified city of Aleppo, which possessed a formidable citadel.1 The Byzantine governor, Youkinna, led the resistance and sallied out to meet the Muslims. Khalid ibn al-Walid engaged Youkinna in single combat and killed him. Following the death of their commander, the garrison surrendered the city.1 Sources are primarily early Islamic histories synthesized by Akram.4

- Battle of Hazir / Qinnasrin (June 637): Near Qinnasrin (ancient Chalcis), Khalid, likely commanding his Mobile Guard, encountered a Byzantine force that had sallied out from the city under their commander Minas (or Menas).4 The battle took place at Hazir, a village near Qinnasrin.4 Minas was killed early in the fierce engagement. Khalid then executed a flanking maneuver with his cavalry, attacking the Byzantine rear, leading to the encirclement and destruction of the Byzantine force.41 The city of Qinnasrin surrendered immediately afterward.4 This victory further secured northern Syria and reportedly earned Khalid grudging admiration from Caliph Umar for his military skill.4 Sources include Tabari, Ibn al-Adim, and Crawford.4

H. Final Command: Siege of Germanicia (Marash) (638)

Khalid's final documented military operation appears to have been leading a campaign into the border regions between Syria and Anatolia (modern Turkey).1 During this expedition in 638, he captured the city of Germanicia (modern Kahramanmaraş, also known as Marash).1 Shortly after this success, marking the northernmost extent of the initial conquests under his command, Khalid was definitively dismissed from military service by Caliph Umar.4

I. Summary Table: Khalid ibn al-Walid's Major Battles/Events in the Syrian Campaign

The conquest of Syria involved numerous significant battles, sieges, and strategic movements against the Byzantine Empire.1 This table summarizes the key events involving Khalid.

J. Reflections on the Syrian Campaign

Khalid's performance in the Syrian campaign cemented his status as a military commander of the highest order. The campaign demonstrated remarkable strategic flexibility. He could execute a high-risk, logistically challenging offensive maneuver like the desert march 1, orchestrate a patient, calculated defensive concentration leading to a decisive counter-offensive as at Yarmouk 4, and employ clever siege tactics involving ruses and exploiting enemy weaknesses, as seen at Damascus and Emesa.4 This adaptability proved crucial in confronting the sophisticated military apparatus of the Byzantine Empire.

The transition in command, with Abu Ubaidah replacing Khalid as supreme commander by order of Caliph Umar 38, occurred during a critical phase of the campaign. Yet, it did not derail the Muslim momentum. Khalid's acceptance of a subordinate role and his continued vital contributions (especially his de facto command at Yarmouk) 4, coupled with Abu Ubaidah's willingness to rely on Khalid's military expertise, points to a significant level of cohesion and shared purpose among the early Muslim leadership. Their ability to prioritize the strategic objectives of the conquest over personal status suggests a strong underlying discipline and commitment to the cause, enabling continued success despite the potentially disruptive change in hierarchy.

Furthermore, the sequence of major battles – particularly Ajnadayn, Fahl, and Yarmouk – illustrates the systematic destruction of Byzantine field armies in the Levant.1 Ajnadayn crippled the southern army, Fahl further weakened resistance in the Jordan Valley, and Yarmouk annihilated the main imperial concentration. After Yarmouk, the nature of the conflict shifted significantly. Byzantine resistance became primarily focused on holding fortified cities rather than challenging the Muslims in open battle. This indicates a fundamental degradation of Byzantine strategic capability in the region, moving from attempts at counter-offensives to a purely defensive posture, ultimately unable to prevent the loss of the entire province.

VI. The Art of War: Khalid's Military Doctrine

Analyzing Khalid ibn al-Walid's campaigns reveals a consistent and effective military approach, often described as a precursor to modern operational art.27 His doctrine was characterized by several key elements:

A. Tactical and Strategic Acumen

Khalid consistently demonstrated a profound understanding of both tactics and strategy. His campaigns were marked by:

- Speed and Mobility: He leveraged the mobility of his Arab forces, particularly camel-mounted infantry for strategic movement and horse-mounted cavalry for tactical shock and pursuit, to outmaneuver slower, heavier opponents like the Sasanians and Byzantines.1 The desert march to Syria is the prime example of strategic mobility.57

- Surprise and Deception: Khalid frequently sought to achieve surprise, whether through unconventional routes (Desert March 57), feints (Battle of Chains 4), night attacks (Muzayyah, Saniyy, Zumail 4), or exploiting enemy complacency (Damascus East Gate assault 4).

- Decisiveness: He aimed for decisive engagement and the complete destruction or routing of enemy forces, often pursuing relentlessly after a victory (e.g., after Ajnadayn 4, Damascus 58).

- Psychological Warfare: Khalid understood the psychological dimension of warfare, using individual duels to eliminate enemy leaders and demoralize troops 4, employing intimidating tactics (Anbar 4), and leveraging his fearsome reputation.

- Adaptability: He proved capable of operating effectively across diverse terrains – desert warfare in Arabia and the Syrian march 57, riverine operations in Iraq 4, open-field battles on plains (Buzakha, Yamama, Walaja, Yarmouk) 4, and complex sieges of fortified cities (Hira, Anbar, Ayn al-Tamr, Damascus, Emesa, Aleppo).4

- Logistics: The successful execution of the waterless desert march indicates a sophisticated understanding of logistical planning, particularly concerning water supply for a large force.57

- Exploiting Weaknesses: He astutely identified and exploited enemy vulnerabilities, such as the immobility of the chained Sasanian infantry at Kazima 4 or the potential for disunity within the multi-ethnic Byzantine army at Yarmouk.4

B. The Mobile Guard (Tulay'a Mutaharrika / Jaish al-Zahf)

A key tactical instrument developed and frequently employed by Khalid was his elite cavalry reserve, known as the Mobile Guard.39 This force, often numbering around 4,000 horsemen, typically remained under Khalid's direct command.39 It was not merely a reserve but a highly mobile, elite strike force used at critical moments to:

- Counter-attack: Blunt enemy breakthroughs and restore the line (e.g., Days 1-3 at Yarmouk 4).

- Flank: Execute decisive flanking maneuvers against engaged enemy forces (e.g., Day 6 at Yarmouk 39, Hazir 41).

- Reinforce: Plug gaps or bolster threatened sectors of the Muslim front.39

- Exploit: Capitalize on opportunities or pursue a broken enemy.

The consistent and effective use of the Mobile Guard highlights Khalid's understanding of the importance of reserves, the decisive potential of concentrated cavalry action, and the need for a commander to retain a flexible force to influence the battle at the critical point. This represents a sophisticated level of tactical thinking and command control.39

C. Maneuver Warfare and Operational Art

While the term "operational art" is a later military concept, Khalid's campaigns exhibit many of its core principles.27 He demonstrated an ability to link tactical actions (battles) to achieve broader strategic objectives (conquest of Hira, securing Syria). His approach emphasized:

- Maneuver: Using movement to gain positional advantage, achieve surprise, and avoid enemy strengths (e.g., Desert March, Kazima feint, Walaja envelopment, Muzayyah convergence).4

- Initiative: Consistently seeking to maintain the initiative, dictating the time and place of engagements.27

- Disruption: Aiming to disrupt the enemy's plans, command structure, and cohesion, rather than simply attriting their forces (e.g., killing commanders in duels, surprise attacks, rapid sequential victories preventing enemy concentration).27

- Tempo: Maintaining a high operational tempo, moving rapidly from one victory to the next, keeping opponents off balance (evident in both Iraq and Syria campaigns).

His campaigns were not just series of isolated battles but interconnected operations designed to achieve specific strategic aims within a resource-constrained environment.27

D. Psychological Dimensions

Khalid was acutely aware of the importance of morale and psychology in warfare. His frequent participation in single combat served not only to eliminate key enemy leaders but also to inspire his own troops and demoralize the opposition.4 His established reputation as "Sayf Allah" and his undefeated record likely preceded him, potentially creating an aura of invincibility that could intimidate opponents. While controversial, actions like the alleged mass executions at Ullais or the public beheading of captives at Dawmat al-Jandal may have been calculated acts intended to break enemy will and demonstrate the futility of resistance.4

Khalid's military system, emphasizing speed, cavalry shock action, maneuver, and decisive engagement, proved exceptionally effective against the more established, often heavier and less flexible, armies of the Byzantine and Sasanian empires.4 His ability to consistently achieve victory, often against numerically superior forces, suggests his tactical approach was well-suited to exploiting the vulnerabilities of his contemporary opponents.

VII. Dismissal, Death, and Enduring Legacy

A. The Dismissal by Caliph Umar (c. 638 CE)

Despite his unparalleled military successes, Khalid ibn al-Walid's career came to an abrupt end not on the battlefield, but through dismissal by Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab around 17 AH (638 CE).4 This occurred shortly after Khalid's successful campaign culminating in the capture of Marash (Germanicia) on the Anatolian frontier.1

The publicly stated reasons centered on financial administration and Khalid's perceived extravagance.4 The immediate trigger was an incident where Khalid gifted 10,000 dirhams to a poet, Ash'ath ibn Qays, who had praised him in verse.4 Upon hearing of this, Umar dispatched strict orders to Abu Ubaidah, the governor of Syria, to publicly investigate Khalid. Khalid was to be asked whether the funds came from official spoils (implying misappropriation) or his personal wealth (implying extravagance). According to Umar's instructions, either answer was grounds for dismissal.4 During the public questioning, reportedly conducted by Bilal ibn Rabah, Khalid initially hesitated but eventually stated the funds were his own.4 He was subsequently relieved of command.4

However, deeper factors likely underpinned Umar's decision. The Caliph expressed concern that the Muslim community was developing an unhealthy personality cult around Khalid, attributing victories to his genius rather than to divine aid. Umar stated he dismissed Khalid partly because "people were glorified by him and were tested by him," fearing they would "rely on him".4 Furthermore, long-standing friction existed between the two men, dating back at least to the controversial Malik ibn Nuwayra affair during the Ridda Wars, where Umar had vehemently condemned Khalid's actions and demanded his punishment, only to be overruled by Abu Bakr.4 Umar may have harbored lingering mistrust or simply had a different vision for military leadership and governance, favoring commanders perceived as more pious and less flamboyant, and seeking to assert stricter central control over the provinces and armies.18

Khalid reacted to his dismissal with shock and a sense of injustice, protesting his treatment to Umar upon being summoned to Medina.4 He reportedly declared his wealth over a certain amount forfeit to the Caliph.4 While Umar reassured Khalid of his personal esteem 4, the dismissal stood. Khalid returned to Syria, likely settling in Homs or Qinnasrin, and never held command again.4 This event highlights the complex interplay between military success, political authority, and religious ideology in the early Caliphate. Umar's actions, while potentially influenced by personal history, represented a clear assertion of caliphal supremacy over even the most successful and popular military figures, a move aimed at ensuring centralized control and preventing the rise of overly powerful, autonomous commanders – a recurring challenge in rapidly expanding empires.

B. Final Years and Death (d. 21 AH / 642 CE)

Khalid ibn al-Walid died not in battle, as he reportedly wished, but from illness in 21 AH (642 CE).18 There is conflicting information in the early sources regarding the location of his death.

- One tradition, reported by historians like al-Waqidi, Ibn Sa'd, and al-Dhahabi, states that he died and was buried in Homs, Syria, where he had lived since his dismissal.18 The Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque in Homs claims to house his tomb.18

- Another tradition, related by Sayf ibn Umar, suggests Khalid spent time in Medina after his dismissal and died there after falling ill, possibly while visiting his mother.18