Abboud, Ibrahim

Sudan's first military head of state (1958-1964). His downfall in the 1964 October Revolution established a precedent for popular uprisings against military rule, a pattern echoed in subsequent Sudanese history.

The Paradox of Paternalism: General Ibrahim Abboud and the Genesis of Military Rule in Sudan (1958-1964)

1. Abstract

This paper examines the political career and legacy of General Ibrahim Abboud, Sudan's first military head of state (1958-1964). It analyzes the conditions leading to the 1958 coup, the nature of Abboud's regime—marked by initial economic stabilization efforts, ambitious development projects, and a paternalistic, authoritarian style—and its ultimate failure, particularly concerning the escalating conflict in Southern Sudan. The paper argues that Abboud's regime, while initially welcomed by some as a solution to political instability, ultimately entrenched military intervention in Sudanese politics and exacerbated the North-South divide through its policies of Arabization and Islamization.1 His downfall in the 1964 October Revolution established a precedent for popular uprisings against military rule, a pattern echoed in subsequent Sudanese history.3 The study draws upon historical accounts, academic analyses, and contemporary reports to assess Abboud's complex legacy and its enduring relevance to understanding Sudan's cyclical political dynamics.

2. Introduction

Ibrahim Abboud (1900-1983) stands as a pivotal figure in the history of post-independence Sudan, having led the nation's inaugural military government from November 1958 until his overthrow in October 1964.5 His tenure marks a critical juncture, interrupting Sudan's brief experiment with parliamentary democracy and ushering in an era where military intervention became a recurring feature of the political landscape.4 Understanding Abboud's rise and fall requires contextualizing the immense challenges confronting Sudan upon achieving independence from Anglo-Egyptian rule on January 1, 1956.8 The nascent republic grappled with the fundamental tasks of nation-building, fostering economic development, and managing profound ethnic, religious, and regional divisions. Foremost among these was the deep cleavage between the predominantly Arab-Muslim North and the diverse African populations of the South, many adhering to Christianity or indigenous beliefs – a division deliberately fostered during the colonial era.10

The initial post-independence parliamentary system (1956-1958) proved tragically short-lived, succumbing quickly to immobilizing factionalism among the major political parties (primarily the Umma Party and the National Unionist Party, NUP, along with the Khatmiyyah-affiliated People's Democratic Party, PDP), allegations of corruption, and crippling economic difficulties, notably a crisis in the crucial cotton sector.9 Perhaps most critically, the civilian governments failed to devise a permanent constitution or effectively address the escalating conflict in Southern Sudan, often referred to as the "Southern Question," where the First Sudanese Civil War had already erupted in 1955.9 The rapid failure of this first democratic experiment underscores the inherent fragility of parliamentary systems transplanted into post-colonial contexts without deep societal roots or robust mechanisms capable of mediating profound internal schisms. The instability was not merely political disagreement but reflected deep structural vulnerabilities – the North-South divide, economic dependency – that the inherited model could not contain.10

It was within this atmosphere of political paralysis and widespread disillusionment that General Abboud, the Commander-in-Chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces, seized power.6 His intervention was initially met with a degree of tacit support, even relief, from segments of the population and political elites weary of the preceding chaos and hopeful for efficient, incorruptible administration.6 This initial acceptance suggests a tension, common in early post-colonial states, between democratic ideals and the perceived imperative of order and stability, particularly following periods of perceived democratic failure.

This paper argues that Abboud's regime represents a defining moment in Sudanese political history. While achieving some measure of economic stability, resolving the Nile Waters dispute with Egypt, and initiating significant development projects, its fundamentally authoritarian nature and, crucially, its aggressive assimilationist policies towards the South proved unsustainable.2 The regime's attempts at forced Arabization and Islamization dramatically intensified the civil war, alienated the Southern population, and ultimately contributed to its own demise.1 The popular civilian uprising that overthrew Abboud in the October Revolution of 1964 established a powerful precedent for challenging military rule in Sudan, a pattern repeated in subsequent decades.3 By examining Abboud's career, the context of his rise, the policies and outcomes of his rule, and the circumstances of his fall, this paper seeks to illuminate the complex legacy of Sudan's first military leader and its enduring relevance for understanding the nation's cyclical struggles between military dominance and popular aspirations for democracy. The analysis will proceed by tracing Abboud's military career, examining the pre-coup context, detailing the 1958 coup, analyzing his governance and economic policies, focusing on the disastrous handling of the Southern Problem, recounting the October Revolution, and finally, assessing his legacy and its echoes in contemporary Sudan.

3. From Soldier to Commander-in-Chief: The Making of a Military Leader

Ibrahim Abboud's path to becoming Sudan's first military ruler was forged through decades of service within the evolving military structures of the region. Born on October 26, 1900, in Mohammed-Gol, near the historic Red Sea port of Suakin, his early life coincided with the consolidation of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium.6 His education reflected the opportunities available to promising Sudanese under colonial rule; he trained initially as an engineer at the Gordon Memorial College in Khartoum, a prominent institution later integrated into the University of Khartoum, before attending the Military College, also in the capital.6

Abboud embarked on his military career in 1918, receiving a commission in the Egyptian Army, which at the time held significant responsibility for Sudan's defence.6 A crucial step came in 1925 when he transferred to the newly established Sudan Defence Force (SDF), created as a distinct entity separate from the Egyptian military, marking an early stage in the development of a specifically Sudanese military identity.6 His service during the Second World War proved formative and distinguished. Abboud saw action in Eritrea and Ethiopia with the SDF, participating in the East African Campaign against Italian forces, and also served with the British Army in the critical North African theatre.6 This wartime experience earned him numerous decorations and cemented his reputation as a brave, disciplined, and capable leader, respected both within the Sudanese forces and by his British counterparts.8 One account, perhaps reflecting his Anglicized demeanor, mentions him being Sandhurst-trained, though primary sources consistently point to his Khartoum-based education.6

In the post-war years, Abboud's career accelerated. After commanding the Camel Corps, a unit with historical significance in Sudan's vast territories, he rose rapidly through the senior ranks.16 He was appointed commander of the Sudan Defence Force in 1949, promoted to General and became assistant commander-in-chief in 1954.6 With Sudan's attainment of independence in 1956, General Abboud was the logical choice to become the first Commander-in-Chief of the independent Sudanese Armed Forces.6 His entire career trajectory exemplified the process of military professionalization and Sudanization occurring under late colonial administration and culminating in the transfer of power. He represented the emergence of a trained, cohesive Sudanese military elite, shaped by the Anglo-Egyptian system but ready to assume national command.

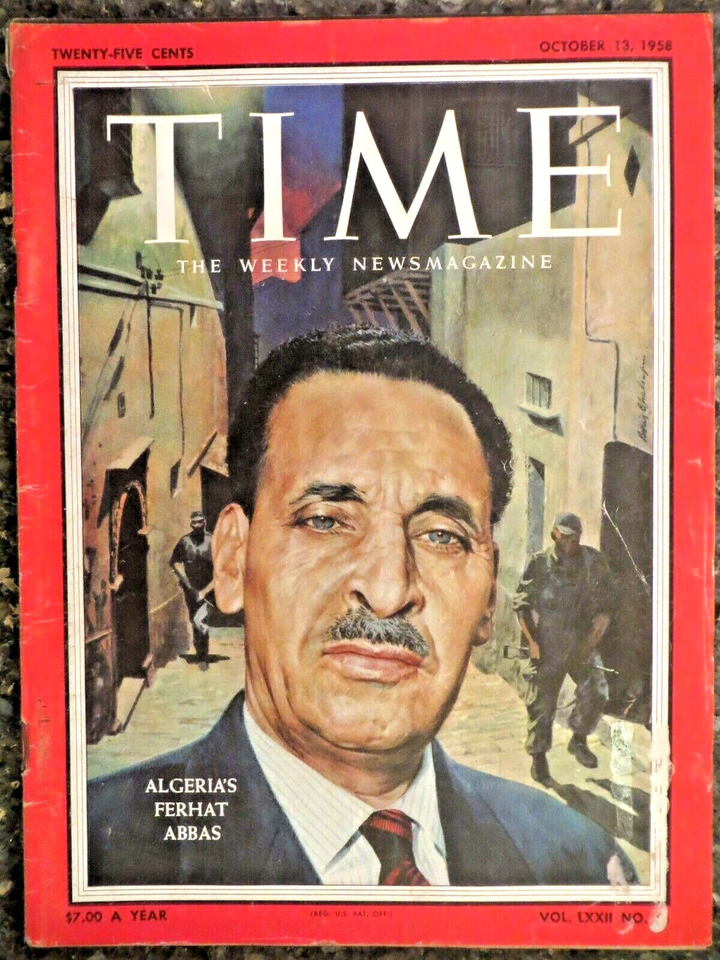

Contemporaries often described Abboud, prior to his political ascension, as being "studiously aloof from politics".6 He cultivated an image of a professional soldier dedicated to the military institution, seemingly detached from the fractious political scene. He was often viewed as a respected, disciplined, and somewhat paternalistic figure, sometimes referred to as "Pappa".4 This carefully maintained apolitical persona proved advantageous when he eventually intervened in 1958. It allowed the coup to be framed not as an act of personal ambition, but as a reluctant, necessary measure undertaken by a respected national figure to rescue the country from chaos.6 This narrative significantly contributed to the initial legitimacy and tacit acceptance his regime received from a population weary of political instability.

4. The Precarious Republic: Sudan 1956-1958

The Republic of Sudan, formally established on January 1, 1956, inherited a complex and challenging legacy.8 The initial governmental structure was a parliamentary republic, headed not by a single president but by a five-member Supreme Commission (or Sovereignty Council) elected by parliament.9 Ismail al-Azhari of the National Unionist Party (NUP) served as the first Prime Minister.9 However, the triumph of achieving independence quickly gave way to the harsh realities of governing a vast, diverse, and underdeveloped nation.

Political instability became the defining characteristic of this brief period. Governments proved short-lived, plagued by shifting alliances and factional infighting.3 Azhari's government fell in July 1956, replaced by a coalition led by Abdallah Khalil of the Umma Party, primarily allied with the People's Democratic Party (PDP).9 This coalition, like its predecessor, struggled with internal divisions. A fundamental point of contention was the inability to agree on a permanent constitution, reflecting deep disagreements about the nature of the state – particularly regarding the balance between secular and Islamic principles, and between unitary and federal structures.9 Parliament often seemed paralyzed by maneuvering, patronage politics, and even allegations of corruption and bribery, rendering it ineffective in addressing the nation's pressing problems.9 This rapid descent into political dysfunction led to widespread popular disillusionment with the democratic experiment.9

Economic challenges compounded the political fragility. Ambitious plans were drafted to expand the education system, transportation infrastructure, and the economy, but these relied heavily on foreign economic and technical assistance, particularly from the United States.9 This dependence itself became a source of political division, with parties like the PDP expressing concerns aligned with Nasserist Arab nationalism about foreign influence.9 The economy's vulnerability was starkly exposed by the performance of its primary export commodity, cotton. A poor harvest in 1957 followed a bumper crop that struggled to find buyers in a saturated global market, severely depleting Sudan's foreign reserves.9 The government responded with unpopular economic restrictions.9 Specific grievances included the government's policy of attempting to sell cotton at prices above the world market rate, leading to low sales, and import restrictions that affected urban populations, alongside an Egyptian embargo on Sudanese livestock and dates impacting rural northerners.9 The cotton crisis of 1957-1958 emerged as a critical destabilizing factor, directly impacting government finances and fueling political discontent.13 This reliance on a single commodity highlighted the precariousness of many post-colonial economies, where external market fluctuations could have immediate and severe domestic political consequences.

Looming over these political and economic woes was the unresolved "Southern Question." The First Sudanese Civil War, ignited by the Torit Mutiny of southern soldiers in August 1955, was already underway.10 The roots of the conflict lay deep in the colonial era's "Southern Policy," which had deliberately segregated the predominantly African, non-Muslim South from the Arabized, Muslim North, fostering inequality and deep mistrust.2 Post-independence "Sudanization" policies largely excluded Southerners from positions of power in the administration and military, reinforcing feelings of marginalization.10 Southern politicians advocated for autonomy or federalism within Sudan, but the central governments in Khartoum failed to stabilize the region or adequately address these demands.9 Repression and violence by government forces were already occurring in the South.10

By late 1958, the convergence of political paralysis, a severe economic crisis centered on cotton, and the intractable, festering conflict in the South had created a perfect storm. The civilian government appeared incapable of managing any of these interconnected crises effectively.9 Popular discontent grew, leading to anti-government demonstrations.9 The stage was set for the military, perceived by some as the only institution capable of imposing order and decisive action, to step in.

5. The 1958 Coup d'état: Genesis and Justification

On the night of November 16-17, 1958, precisely the day the fractious parliament was scheduled to reconvene, the Sudanese military intervened decisively in the nation's politics.9 In a swift and bloodless coup, Commander-in-Chief General Ibrahim Abboud, aided by senior officers including Brigadier Ahmad Abd al Wahab, overthrew the civilian coalition government of Prime Minister Abdallah Khalil.3 The military deployed troops around Khartoum, declared a state of emergency, briefly detained government ministers, dissolved parliament and all political parties, and abolished trade unions.4

Abboud justified the military takeover as a necessary measure to end what he described as "the state of degeneration, chaos, and instability of the country".6 He pledged his regime to the "realization of the country's paramount interests" and promised to inaugurate an "efficient and incorruptible administration".6 This rhetoric resonated with a populace and political class exhausted by the perceived failures, intrigues, and ineffectiveness of the preceding parliamentary governments.6 Consequently, the coup initially encountered little overt opposition and garnered tacit support, viewed by many as a potentially stabilizing, if temporary, intervention.4 International recognition followed rapidly, with Egypt, the United Kingdom, Jordan, and several other regional powers acknowledging the new military government within days.21 A contemporary US intelligence assessment concluded that Abboud's junta would likely provide "more effective leadership" than its predecessors, at least in the short term.25 This swift international acceptance and pragmatic assessment reflected a Cold War geopolitical context where stability and a perceived reliable (or at least non-hostile) orientation were often prioritized by external powers over the niceties of democratic legitimacy.

Intrigue surrounded the circumstances of the coup, with persistent suggestions that the outgoing Prime Minister, Abdallah Khalil – himself a retired army general – may have actively encouraged or even planned the coup in conjunction with Abboud and elements within his own Umma Party.4 The motive, according to this interpretation, was to preempt further political instability or challenges within the parliamentary system, effectively using the military to sideline democratic processes. If accurate, this complicates the narrative of a straightforward military versus civilian conflict, suggesting instead a reconfiguration of power among established elites, with the military assuming direct control at the behest, or with the complicity, of civilian figures unable to manage the political system.

Further controversy surrounds the coup regarding potential external influence. Philip Agee, a former CIA case officer turned prominent critic of the agency, alleged in his 1975 book, Inside the Company: CIA Diary, that the CIA had engineered the 1958 coup.16 Agee's own history is complex; he was accused by US sources and defectors of collaborating with Cuban and Soviet intelligence after leaving the CIA, charges he consistently denied, maintaining his actions were driven by conscience.26 While Agee's book provided detailed accounts of CIA operations elsewhere, often based on his direct experience, his claim regarding the Sudan coup lacks independent corroboration in the available materials.26 The extensive documentation of Sudan's internal political breakdown, the severe economic crisis linked to cotton, and the specific actions of Sudanese political figures like Khalil provide a compelling and well-substantiated explanation for the coup based on domestic factors.9 Furthermore, the declassified US Special National Intelligence Estimate from January 1959 analyzes the consequences and likely trajectory of Abboud's regime, focusing on its potential stability, conservatism, non-alignment, and relationship with Egypt and the West, without indicating any US role in its installation.25 While the possibility of covert external involvement can rarely be definitively excluded in such historical events, the available evidence strongly points to internal dynamics as the primary drivers of the 1958 coup in Sudan. The Agee allegation highlights the persistent challenge of assessing external influence versus potent domestic factors in post-colonial political upheavals.

6. Governing Sudan: The Supreme Council and Economic Policy (1958-1964)

Upon taking power, General Abboud established the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces as the ruling body of Sudan.9 Initially composed of twelve, later eleven, senior military officers, this council effectively replaced the civilian cabinet and parliament.6 In an attempt to manage traditional power structures, the council included officers affiliated with the country's two main religious sects, the Ansar (associated with the Umma Party) and the Khatmiyyah (associated with the PDP); Abboud himself belonged to the Khatmiyyah, while his initial deputy, Ahmad Abd al Wahab, was Ansar.9 The regime immediately suspended the provisional constitution, dissolved all political parties, banned public assemblies, and imposed restrictions on the press, consolidating its authoritarian grip.4 Practices such as 'preventative arrest' were reportedly introduced, and opponents, including members of political parties, allegedly faced harsh treatment.2

Despite the initial tacit acceptance, the military government faced internal challenges early on. Disagreements emerged among the senior military leadership in the first few months.6 More significantly, within a year, challenges arose from younger, possibly more ideologically driven officers and even cadets.6 These were swiftly suppressed. A notable instance was a failed coup attempt in November 1959, which resulted in the trial and execution of the involved officers, signaling the regime's intolerance of internal dissent within the armed forces.2 This early suppression of internal military opposition foreshadowed the inherent fragility often lurking beneath the surface of seemingly unified military regimes, hinting at potential fault lines between conservative senior leadership and more radical junior ranks, as noted in contemporary US intelligence assessments.25

Economically, the Abboud regime moved decisively to address the crisis it inherited. A key early success was tackling the cotton situation. By lowering the artificially high prices set by the previous government, the regime managed to sell off the surplus from the 1958 crop and the subsequent bumper crop of 1959, significantly easing the financial crisis and helping to rebuild the nation's depleted foreign reserves.6

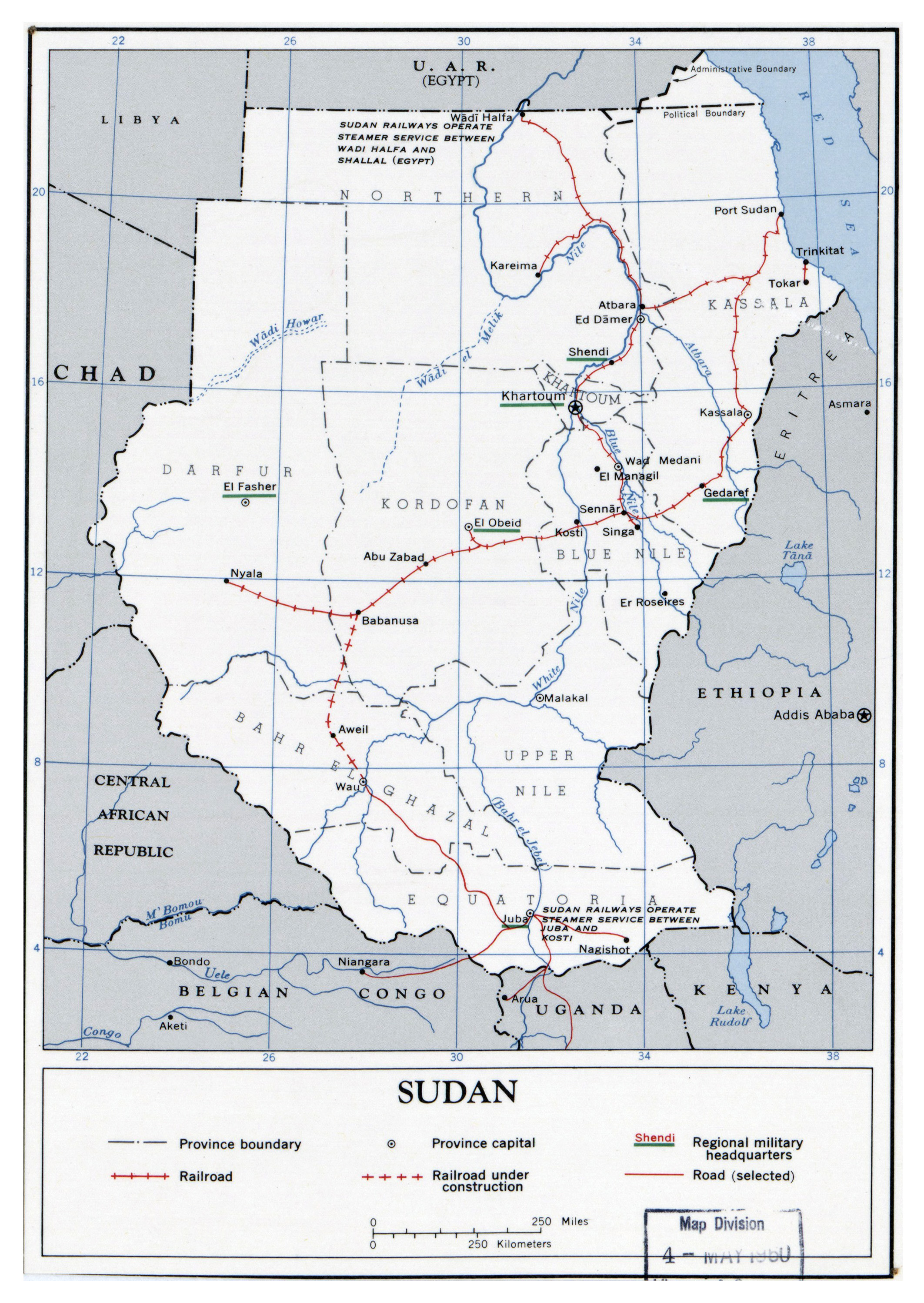

A landmark achievement of Abboud's government was the conclusion of the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement with Egypt (formally the United Arab Republic at the time).4 This agreement resolved the long-standing and contentious issue of sharing the river's flow, which had hampered bilateral relations and stalled major development plans. The agreement established a framework for the "full utilization" of the Nile waters, settling on an average annual flow of 84 billion cubic meters (BCM) measured at Aswan. Of this, Sudan was allocated 18.5 BCM and Egypt 55.5 BCM, with 10 BCM attributed to evaporation and seepage losses.33 Crucially, the agreement granted Egypt the right to proceed with the construction of the Aswan High Dam, while explicitly permitting Sudan to construct the Roseires Dam on the Blue Nile and undertake other projects to utilize its allocated share.33 It also committed both countries to adopt a "united view" regarding any future claims by upstream riparian states.36

The 1959 Agreement was significant on multiple fronts. Diplomatically, it marked a major improvement in relations with Egypt, which formally recognized Sudan's independence and ceased frontier disputes.6 Domestically, it was pivotal because it provided the necessary political and legal certainty for Sudan to embark on large-scale water development projects, which were central to the regime's economic strategy and claims to legitimacy.9 However, the agreement's bilateral nature, completely ignoring the water rights and needs of upstream countries like Ethiopia (the source of over 80% of the Nile's flow), sowed the seeds of future hydro-political conflict in the basin, a controversy that continues to this day.33

With the Nile Waters issue seemingly settled, the Abboud regime pursued an ambitious, state-led development agenda, characteristic of the post-colonial developmentalist ideology prevalent at the time.15 This agenda was formalized in the Ten-Year Economic and Social Development Plan (1961-1970).15 Key infrastructure projects initiated or significantly advanced during this period included:

- The Managil Extension: A major expansion of the existing Gezira Scheme, the vast irrigated cotton plantation between the Blue and White Niles. Completed in 1962, it significantly increased the land under cultivation for cotton, Sudan's primary export earner.12

- The Roseires Dam: A large dam on the Blue Nile intended primarily for storing water for irrigation (including the Managil Extension) and generating hydroelectric power. Construction began under Abboud, financed partly through loans from the World Bank (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), and West Germany, although it was not completed until after his rule.15

- The Khashm el-Girba Dam and Resettlement Scheme: Located on the Atbara River, this project involved constructing a dam and creating a new agricultural settlement area, primarily to resettle the Nubian population from the Wadi Halfa region whose lands were inundated by the Aswan High Dam reservoir (Lake Nasser).15

Table 1: Key Economic Policies and Development Projects under Abboud (1958-1964)

| Policy Area | Specific Action | Key Dates | Funding Sources (Examples) | Intended Goal | Relevant Snippets |

| Cotton Marketing | Lowered export price, sold 1958/59 surplus | 1958-1959 | - | Ease financial crisis, rebuild reserves | |

| Nile Waters | Signed Nile Waters Agreement with Egypt | Nov 1959 | - | Settle water allocation, enable dam construction | |

| Irrigation | Managil Extension (Gezira Scheme) | Completed 1962 | Domestic/State | Expand cotton production | |

| Dam Construction | Roseires Dam (Blue Nile) initiated | Begun c. 1961 | IBRD, IDA, West Germany | Irrigation water storage, hydroelectric power | |

| Dam/Resettlement | Khashm el-Girba Dam & Town (Atbara River) initiated | Begun c. 1961 | Domestic/State | Resettle population displaced by Aswan Dam, agriculture | |

| National Planning | Launched Ten-Year Development Plan (1961-1970) | 1961 | Domestic & Foreign Loans | Broaden economy, increase income/exports, import sub. | |

| Industrialization | Sugar factories, Jute industry planned | Early 1960s | - | Import substitution, diversification |

Table 2: Summary of the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement Terms (Sudan-Egypt)

| Aspect | Value / Provision | Relevant Snippets |

| Agreed Avg. Annual Flow | 84 BCM (measured at Aswan) | |

| Egypt's Allocation | 55.5 BCM per year | |

| Sudan's Allocation | 18.5 BCM per year | |

| Evaporation/Loss Allowance | 10 BCM per year | |

| Stated Purpose | "Full Utilization" of Nile waters | |

| Key Permissions (Egypt) | Build Aswan High Dam | |

| Key Permissions (Sudan) | Build Roseires Dam, develop share fully | |

| Stance on Upstream Claims | Adopt a "united view" against claims | |

| Status of 1929 Agreement | Superseded / Updated | |

| Handling of Future Increases | Increased yield shared equally between Egypt & Sudan | |

| Handling of New Upstream Claim | Allocation deducted equally from Egypt & Sudan |

While these development efforts led to some economic improvement and a noted rise in per capita GDP during Abboud's rule 11, they also attracted criticism. The concentration of investment in large-scale irrigated agriculture, primarily cotton, in the central riverine region reinforced existing economic structures and exacerbated regional inequalities, neglecting the peripheries, particularly the South, and other potential sectors like livestock.15 This focus on capital-intensive projects also deepened Sudan's reliance on foreign loans and aid, raising concerns about long-term debt sustainability.15

In foreign relations, Abboud navigated a path of non-alignment. While seeking continued economic and technical assistance from the West, particularly the US and UK, the regime avoided the overtly pro-Western stance of its predecessor, Khalil.25 Abboud's visit to the White House in 1961 symbolized these ties.6 Simultaneously, relations with Nasser's Egypt improved significantly following the Nile Waters Agreement.6 The regime maintained neutrality in broader Arab conflicts unless Sudan's interests were directly affected and pursued ties with other African nations.25 US intelligence anticipated a potential gradual increase in ties with the Soviet Bloc, particularly through trade.25 Abboud's regime, therefore, projected an image of pragmatic nationalism, focused on domestic development and maintaining balanced international relationships.

7. The Southern Problem: Intensification of Conflict under Military Rule

The Abboud regime inherited the nascent First Sudanese Civil War, which had begun in 1955 following the Torit Mutiny.10 However, rather than seeking political accommodation, Abboud's government adopted policies that dramatically escalated the conflict, turning a tense situation into a full-blown, devastating war.10 The regime's approach was rooted in a belief that national unity could only be achieved through the imposition of a singular Northern Arab-Islamic identity across the entire country.11 This ignored the distinct historical, cultural, ethnic, and religious identities of the Southern Sudanese populations and the legacy of mistrust sown by colonial policies that had deliberately separated North and South.2

Central to the regime's strategy was a vigorous and coercive program of Arabization and Islamization in the South.1 Specific measures included:

- Language Policy: Replacing English with Arabic as the medium of instruction in Southern schools.11

- Education Control: Enforcing the nationalization of Christian mission schools (a process begun in 1957 but rigorously pursued under Abboud) and forbidding missionaries from establishing new schools.2

- Religious Policy: Expelling foreign Christian missionaries, particularly between 1962 and 1964 11, restricting Christian practice outside churches 50, promoting Islam through state funding (e.g., for the Directorate of Religious Affairs in the South 2), and imposing the Islamic day of rest (Friday) instead of Sunday.2

- Administrative Control: Staffing key positions in the Southern administration and police forces predominantly with Northern Sudanese.11

These policies were met with widespread and determined resistance in the South. School strikes erupted in protest, notably in October 1962.6 Anti-government demonstrations occurred, and open revolt intensified in the countryside.2 The Anya-Nya guerrilla movement, seeking autonomy or independence for the South, gained strength and recruits during this period, becoming a more organized and effective resistance force.10

The government responded to this resistance with escalating force and repression.6 Military reprisals against communities suspected of supporting the rebels became common. Abboud's forces were implicated in significant civilian deaths in towns like Kodok, Yei, and Maridi.16 Reports, building on patterns established after the 1955 mutiny, suggested widespread atrocities by Northern troops, including torture, mutilation, and summary executions.10 One assessment grimly notes that Abboud's government was responsible for more Sudanese deaths than any preceding head of state, a record unsurpassed until the era of Omar al-Bashir.16

The human consequences were catastrophic. The civil war intensified dramatically.1 Casualty estimates for the entire First Civil War (1955-1972) are staggering, typically ranging from 500,000 to 1 million deaths.10 While isolating precise figures for the 1958-1964 period is difficult from the available data, one contemporary report suggested that perhaps half a million people had already been killed by 1964.3 Furthermore, the violence and repression forced thousands of Southern Sudanese civilians to flee their homes and seek refuge in neighboring countries, particularly Uganda.6 This policy of forced assimilation, therefore, was not merely ineffective but actively counterproductive, directly fueling the conflict it claimed to prevent and creating a major humanitarian crisis.

By August 1964, facing a costly and unwinnable military campaign in the South, the Abboud regime appeared to acknowledge the failure of its coercive approach. In a desperate attempt to find a way out, Abboud established a 25-man commission tasked with studying the "Southern Problem" and recommending solutions.6 Ironically, the regime's subsequent decision to allow public debate on the commission's work, intended perhaps to deflect criticism, provided the spark that ignited the popular uprising in the North.12 The Southern war, exacerbated by Abboud's policies, thus became inextricably linked to the regime's own downfall, demonstrating how the failure of a centralized, assimilationist nation-building model in the diverse South created a political crisis that ultimately consumed the central government itself.

Table 3: Abboud Regime Policies Towards Southern Sudan and Documented Consequences (1958-1964)

| Policy Area | Specific Policy | Year Implemented/Intensified (Approx.) | Documented Consequence | Relevant Snippets |

| Education Language | Arabic replaces English as medium of instruction | Intensified 1958-1964 | School strikes (e.g., Oct 1962), Southern alienation | |

| Religious Practice | Missionary expulsion/restrictions, Promote Islam | Intensified 1962-1964 (expulsions) | Growth of resistance, Southern alienation, International criticism | |

| School Admin. | Nationalization of mission schools enforced | Intensified 1958 onwards | School strikes, Reduced educational access (initially), Southern resentment | |

| Governance/Staffing | Northern administrators/police appointed | Intensified 1958-1964 | Southern marginalization, Mistrust, Fueling resistance | |

| Day of Rest | Friday imposed instead of Sunday | c. 1960 | Student strikes, Religious alienation | |

| Military/Security | Increased military presence, Repression, Reprisals | Intensified 1958-1964 | Increased violence/casualties (e.g., Kodok, Yei, Maridi), Growth of Anya-Nya, Refugee outflows, Trigger for Oct Rev |

8. The October Revolution of 1964: The Fall of the First Military Regime

By 1964, six years of military rule under General Abboud had generated significant, albeit often suppressed, discontent within Sudan. While the regime had brought a degree of economic stability and initiated development projects, its authoritarian nature chafed against a population with recent experience of political participation.11 The suspension of the constitution, the banning of political parties and free assembly, and press censorship fostered resentment, particularly among the urban educated elites – the intelligentsia, professionals, students, and trade unionists who had been active in the pre-coup era.3 Economic grievances, such as the rising cost of living, also contributed to the undercurrent of dissatisfaction.50

However, the most potent catalyst for the regime's downfall was its disastrous handling of the escalating war in Southern Sudan.3 The brutal and ineffective policies of Arabization and Islamization had inflamed the conflict, leading to immense suffering and draining national resources. Recognizing the impasse, the regime itself created the spark for its demise when, in late 1964, it allowed public discussion surrounding the commission established to study the Southern problem.6

The sequence of events unfolded rapidly in October 1964:

- October 21: Defying a government ban on discussing the sensitive Southern issue, the Khartoum University Students' Union (KUSU) held a meeting on campus.17 The meeting turned into a critique of the military regime's failure to resolve the conflict. Police forces intervened violently, using tear gas and eventually opening fire on the students.17 Several students were wounded, and one, Ahmed Al-Qurashi Taha, was killed.17 The death of this single student acted as a powerful symbol of the regime's brutality and became the immediate catalyst that transformed simmering discontent into mass mobilization.

- October 22: The funeral procession for Al-Qurashi swelled into a massive anti-government demonstration, with estimates of over 30,000 participants marching through Khartoum, led by university faculty chanting slogans demanding the fall of the regime.17 In a significant act of defiance, the Sudanese university staff collectively tendered their resignations, conditional on the end of military rule and the restoration of constitutional government.50

- October 23-24: The political momentum grew. The Umma Party issued a statement condemning the regime.50 Student demonstrations erupted in other major towns, including Omdurman, Juba, and Port Sudan.50 Crucially, organized professional groups – lawyers, judges, engineers, doctors, teachers – attempted to present a petition protesting government brutality. When blocked, they declared their intention to launch a general strike.17

- October 25: A powerful coalition, the United National Front (UNF), was formed, bringing together the newly mobilized professionals, the previously banned political parties (Umma, NUP, Communist Party, Muslim Brotherhood's Islamic Charter Front), and influential trade unions.12 This broad front demonstrated the necessity of cross-sectoral alliances to effectively challenge the military regime.

- October 26: The general strike, spearheaded by the UNF and involving key sectors like transport workers and the civil service, effectively paralyzed Khartoum and other urban centers.4 Faced with this overwhelming display of popular opposition and the breakdown of state function, General Abboud dissolved his government and the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.4

The transition back to civilian rule unfolded over the next few weeks. A provisional cabinet was formed under the respected civil servant Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa to replace the Supreme Council.9 Reports suggest that divisions appeared within the military itself, with some junior officers expressing sympathy for the protestors and senior figures possibly facilitating the transition to avoid further bloodshed or a complete collapse of order.4 Abboud himself, seemingly unwilling to order a large-scale massacre of unarmed civilians, was ultimately compelled to resign completely on November 15, 1964.6 He retreated quietly into retirement, thus ending Sudan's first, six-year experiment with military rule.5

The October Revolution was remarkable for its largely non-violent character, driven by popular mobilization rather than armed struggle.3 Abboud's relatively peaceful departure, possibly influenced by senior military figures acting as 'caretakers' of the transition who ensured no subsequent recriminations against the outgoing regime 4, shaped the nature of the handover. While celebrated as a victory for people power, this negotiated exit also allowed the military as an institution to withdraw from direct governance temporarily while retaining its underlying structure and influence, setting the stage for future interventions. The October Revolution became deeply embedded in Sudan's political consciousness as a testament to the power of civilian resistance, influencing subsequent popular uprisings against military rule in 1985 and 2018-19.4

9. Legacy and Echoes in Modern Sudan

The six-year rule of General Ibrahim Abboud cast a long shadow over Sudan's subsequent political development, establishing precedents and exacerbating cleavages whose consequences continue to resonate deeply in the 21st century. His primary legacy lies in initiating the pattern of direct military intervention in Sudanese politics.4 The 1958 coup, less than three years after independence, shattered the nascent democratic framework and normalized the idea that the armed forces could, and perhaps should, step in when civilian governance faltered. This act created a powerful path dependency; Sudan has subsequently spent the majority of its independent history under military rule, punctuated by brief and often unstable periods of civilian government.4

Abboud's rise and fall established the first iteration of a cycle that would become tragically familiar in Sudan: military coup, followed by authoritarian consolidation, leading eventually to widespread popular discontent culminating in a civilian uprising, a transitional period, the restoration of fragile democratic institutions, subsequent political instability, and ultimately, another military intervention.3 The regimes of Jaafar Nimeiry (1969-1985) and Omar al-Bashir (1989-2019) followed Abboud's path into power via coups, while the popular uprisings of October 1964, the April Intifada of 1985, and the Sudanese Revolution of 2018-2019 mirrored the civilian resistance that unseated him.4 Just as Abboud's coup set the precedent for military rule, the 1964 October Revolution established the enduring template for successful, largely non-violent popular resistance against military dictatorships in Sudan, inspiring subsequent generations.4

Beyond the political structure, Abboud's policies had lasting negative consequences, particularly regarding the North-South conflict. His administration's aggressive pursuit of Arabization and Islamization significantly intensified the First Sudanese Civil War, deepened the animosity between the regions, and established a pattern of coercive assimilation by the central state.1 This approach arguably influenced how later regimes dealt not only with the South but also with other marginalized peripheral regions like Darfur and the Nuba Mountains.2 The failure to find a political solution during his tenure contributed to decades of devastating conflict, which ultimately led to the separation of South Sudan in 2011.4

The authoritarian practices employed by the Abboud regime, such as the dissolution of parties, suppression of the press, and the reported use of preventative detention and torture, became part of the toolkit for subsequent military and authoritarian governments in Sudan.2 Economically, while Abboud oversaw a period of significant state-led development and infrastructure investment, the concentration of these projects in the central riverine areas arguably entrenched, rather than alleviated, the country's severe regional economic inequalities.15 The reliance on foreign loans to finance these ambitious schemes also contributed to patterns of external debt that would burden future generations.15

The manner of Abboud's departure in 1964, a relatively peaceful transition without major purges or recriminations against the military leadership, allowed the armed forces to retain considerable institutional power and prestige.4 The military remained a central actor in Sudanese politics and economy, capable of intervening again when civilian governments faltered, as demonstrated by the coups of 1969 and 1989.

The echoes of Abboud's era are strikingly evident in contemporary Sudan. The 2018-2019 revolution that overthrew Omar al-Bashir shared many characteristics with the 1964 uprising: mass mobilization led by professionals (organized under the Sudanese Professionals Association) and youth, the use of general strikes and civil disobedience, and demands for civilian democratic rule.62 The subsequent, ongoing power struggle between civilian political forces and rival military factions (the Sudanese Armed Forces, SAF, and the Rapid Support Forces, RSF), which erupted into open warfare in April 2023, tragically underscores the enduring difficulty of establishing stable civilian supremacy over the military institution whose political primacy Abboud first asserted.13 The core issues that defined Abboud's time – the challenge of managing ethnic and religious diversity, the deep economic and political cleavages between the center and peripheries, the struggle over national identity, and the oversized role of the military – remain the fundamental, unresolved problems fueling Sudan's cycles of conflict and instability.2 Abboud's regime did not create these problems, but its actions entrenched them, leaving a legacy that Sudan continues to grapple with.

10. Conclusion

The political career of General Ibrahim Abboud represents a crucial and paradoxical chapter in Sudan's post-independence history. Ascending to power in 1958 amidst the perceived chaos and failure of the country's first democratic experiment, Abboud, a respected military figure, initially embodied hopes for stability, efficiency, and national progress.6 His regime achieved notable early successes, particularly in stabilizing the economy after the cotton crisis, concluding the vital 1959 Nile Waters Agreement with Egypt, and launching ambitious development projects intended to modernize the nation.6

However, this paternalistic pursuit of order and development was inextricably linked to an authoritarian political structure that suppressed dissent and dismantled nascent democratic institutions.6 More devastatingly, the regime's pursuit of national unity through a policy of forced Arabization and Islamization in Southern Sudan proved disastrous.1 Rather than fostering integration, these policies inflamed Southern resistance, dramatically intensified the First Sudanese Civil War, caused immense human suffering, and ultimately became a primary catalyst for the regime's own downfall.2

The 1964 October Revolution, a largely peaceful popular uprising led by students and professionals, stands as a significant event not only for ending Abboud's rule but also for establishing a powerful precedent of civilian resistance against military dictatorship in Sudan.4 Yet, the revolution did not fully resolve the underlying tensions. The manner of Abboud's exit allowed the military institution to retain significant influence, paving the way for future interventions and perpetuating a cycle of political instability.4

Ibrahim Abboud's legacy is therefore complex and contested. He was neither a simple villain nor a national savior. He was a product of his time, a military leader who responded to a genuine crisis of civilian governance but whose solutions ultimately deepened the nation's fundamental problems. His era solidified the military's role as a central political actor, entrenched the devastating conflict between the North and South, and highlighted the immense challenges of building a unified and equitable nation-state in the face of deep historical, cultural, and economic divisions. The enduring struggles of Sudan – the cyclical battle between military power and civilian aspirations, the persistent conflicts rooted in identity politics and regional inequality, and the difficult management of resources like the Nile waters – all bear the imprint of the path taken during Abboud's pivotal six years in power. His story remains a crucial reference point for understanding the forces that continue to shape Sudan's turbulent political trajectory.

11. References

- Agee, Philip. Inside the Company: CIA Diary. Penguin Books, 1975. 26 (Referenced in relation to allegations in 16).

- AfricaBib. "Sudan's Khashm El Girba scheme gets under way: new settlers start cultivation." African World, April 1964, p. 20. Accessed via AfricaBib.46

- AfricaBib. "Economic development in the Sudan." Economic Bulletin - National Bank of Egypt, vol. 14, no. 2, 1961, pp. 224-237. Accessed via AfricaBib.44

- AfricaBib. Query results for author Scopas Poggo. https://www.africabib.org/query_a.php?au=!239702824!.69

- Africanews. "Explainer: Colonial agreements governing Nile waters can't stop Ethiopia - former PM." Africanews, 28 April 2018. https://www.africanews.com/2018/04/28/explainer-colonial-agreements-governing-nile-waters-can-t-stop-ethiopia-former//.41

- African Arguments. "50 years on: Remembering Sudan’s October Revolution – By W.J. Berridge." African Arguments, 20 October 2014. https://africanarguments.org/2014/10/50-years-on-remembering-sudans-october-revolution-by-willow-berridge/.17

- ADST (Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training). "‘I Know a Coup is Coming, But No One Will Listen’ – Sudan, 1964." ADST.org, June 2017. https://adst.org/2017/06/know-coup-coming-no-one-will-listen-sudan-1964/.3

- AJOL (African Journals Online). Article referencing 1929 and 1959 Nile Agreements. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/asr/article/download/51433/40090/0.40

- Barnes & Noble. Overview of The First Sudanese Civil War by Scopas S. Poggo. https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-first-sudanese-civil-war-s-poggo/1118014512.53

- Berridge, W.J. (Referenced in Poggo 2, full citation needed).

- Beswick, Stephanie F. (1991). (Referenced in 13, full citation needed).

- BlackPast.org. "First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972)."https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/first-sudanese-civil-war-1955-1972/.54

- Bridging Cultures Bookshelf: Muslim Journeys. "Sudan Timeline." https://bridgingcultures-muslimjourneys.org/items/show/139.14

- Brill. Abstract mentioning Poggo's article on Abboud. https://brill.com/view/journals/jra/38/4/article-p467_6.pdf.49

- Brookings Institution. "The limits of the new Nile agreement." Brookings, 1 April 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-limits-of-the-new-nile-agreement/.34

- Cambridge University Press. Chapter: "The Nation, in Whose Name They Could Act: The Military and National Income Accounting, 1958–1964." In Transforming Sudan. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/transforming-sudan/nation-in-whose-name-they-could-act-the-military-and-national-income-accounting-19581964/262F1666925FFBC228288F163370E52F.15

- Cambridge University Press. Chapter: "A Nation-State Alone Cannot Transform Its Destiny, 1964–1966." In Transforming Sudan. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/transforming-sudan/nationstate-alone-cannot-transform-its-destiny-19641966/B98CA865FE071A8AE09349F34C788E8A.48

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "Sudan’s Conflict in the Shadow of Coups and Military Rule." Sada Journal, August 2023. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/2023/08/sudans-conflict-in-the-shadow-of-coups-and-military-rule.7

- Casa África. "Ibrahim Abboud." https://www.casafrica.es/en/person/ibrahim-abboud.8

- CIA Reading Room. Document discussing CIA activities (Chile example). https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP77-00432R000100340005-5.pdf.70

- CIA Reading Room. Document mentioning Philip Agee and CIA activities. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP77-00432R000100340003-7.pdf.71

- Colab.ws. Abstract mentioning Poggo's article on Abboud. https://colab.ws/articles/10.1353%2Fnas.2007.0002.72

- Contemporary And (C&). "Remembering the Sixties and Seventies." https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/remembering-the-sixties-and-seventies/.59

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). "Global Conflict Tracker: Power Struggle in Sudan." https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/power-struggle-sudan.67

- Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF) South Sudan. Entry for Poggo's article on Abboud. https://www.csrf-southsudan.org/repository/general-ibrahim-abbouds-military-administration-sudan-1958-1964-implementation-programs-islamization-arabization-southern-sudan/.73 (Also see staging link 74).

- Cross, T. (2023). (Referenced in 13, full citation needed).

- Cut and Style Co. "Understanding the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement: A Legal Analysis." Cut and Style Co Blog, 30 August 2023. https://cutandstyle.co/index.php/2023/08/30/understanding-the-1959-nile-waters-agreement-a-legal-analysis/.75

- Davies, Daniel. (2022). (Referenced in 64, full citation needed).

- DeRouen, Karl R., and Uk Heo, eds. Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts Since World War II. ABC-CLIO, 2007. (Referenced in 22).

- Digital Commonwealth. Photo caption: "Takes over Power in Sudan--Ibrahim Abboud..." Associated Press, c. Oct 1964. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:fq97bv93p.31

- Digital Commonwealth / Boston Public Library. Photo caption: "Personalities in Sudan Coup– Gen. Ibrahim Abboud..." Associated Press, Nov 1958. . https://dp.la/item/a8df6d3dc565093640b6f23da3b55ca9.24

- Dokumen.pub. Entry for Transforming Sudan: Decolonization, Economic Development, and State Formation. https://dokumen.pub/transforming-sudan-decolonization-economic-development-and-state-formation-9781107172494-1107172497.html.43

- EBSCO Research Starters. "First Sudanese Civil War Erupts." https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/first-sudanese-civil-war-erupts.10

- Elamin, Nisrin. Interview in Stanford Daily. "Elamin calls for attention, aid to Sudan." Stanford Daily, 30 September 2024. https://stanforddaily.com/2024/09/30/elamin-calls-for-attention-aid-to-sudan/.68

- Encyclopedia Britannica. "Sudan: The growth of national consciousness." https://www.britannica.com/place/Sudan/The-growth-of-national-consciousness.11

- Encyclopedia.com. "El Ferik Ibrahim Abboud." https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/el-ferik-ibrahim-abboud.6

- E-International Relations (E-IR). "Is Identity the Root Cause of Sudan’s Civil Wars?" E-IR, 9 April 2012. https://www.e-ir.info/2012/04/09/is-identity-the-root-cause-of-sudans-civil-wars/.22

- Ethiopians.com. "Engineering Perspective on the Nile River Treaties." https://www.ethiopians.com/abay/engin.html.76

- FairPlanet. "What's at Stake in the Egypt-Ethiopia Conflict Over the Nile?" https://www.fairplanet.org/dossier/water-2/whats-at-stake-in-the-egypt-ethiopia-conflict-over-the-nile/.37

- FOI (Swedish Defence Research Agency). "FOI Memo 8661: Sudan's Civil War." https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI%20Memo%208661.66

- Good Times Web. PDF of Inside the Company by Philip Agee. https://goodtimesweb.org/covert-operations/2014/Inside-the-Company-by-Philip-Agee.pdf.28

- Good Times Web. PDF of In Search of Enemies by John Stockwell. https://goodtimesweb.org/covert-operations/2014/In-Search-of-Enemies-A-CIA-Story-John-Stockwell.pdf.27

- Historical Materialism. "Uprising in Sudan: Interview with Sudanese Comrades." https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/uprising-in-sudan-interview-with-sudanese-comrades/.63

- IGAD Land Governance Portal. "Agriculture Policy in Sudan." https://land.igad.int/index.php/documents-1/countries/sudan/rural-development-6/1138-agriculture-policy-in-sudan/file.45

- IMF eLibrary. "Foreign Trade and Balance of Payments of the Sudan, 1947–62." Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, vol. 11, no. 1, 1964, pp. 145-168. https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/024/1964/001/article-A005-en.xml.77

- International IDEA. "War in Sudan 15 April 2023: Background, Analysis and Scenarios." September 2023. https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/2023-09/war-in-sudan-15-april-2023-background-analysis-and-scenarios.pdf.64

- International Waters Governance. "Nile River Basin Initiative." http://www.internationalwatersgovernance.com/nile-river-basin-initiative.html.36

- ISS Forum. Review Essay on War and Conflict in South Sudan. https://issforum.org/essays/PDF/E404.pdf.78

- Italiaander, Rolf. The New Leaders of Africa. Prentice-Hall, 1961. (Referenced in 6).

- IWA Publishing. "The long shadow of the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement." Water Policy, vol. 26, no. 9, 2024, pp. 859-869. https://iwaponline.com/wp/article/26/9/859/104258/The-long-shadow-of-the-1959-Nile-Waters-Agreement.39

- Johnson, Douglas H. The Root Causes of Sudan's Civil Wars. Indiana University Press, 2003. (Referenced in 22).

- Library of Pima County. PDF: Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner (likely source of snippet). https://www.library.pima.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2020/09/Agency-a-History-of-the-CIA-8000.pdf.79

- Macrotrends. "Sudan Exports 1980-2024." https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/SDN/sudan/exports.80

- MERIP (Middle East Research and Information Project). "Sudan: Politics and Society." MERIP, no. 172, September 1991. https://merip.org/1991/09/sudan-politics-and-society/.61

- Minorities at Risk Project (MAR), University of Maryland. "Chronology for Southerners in Sudan." http://www.mar.umd.edu/chronology.asp?groupId=62501.81

- MUSE (Project MUSE), Johns Hopkins University Press. Entry for Poggo article in Northeast African Studies. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/214956.1

- MUSE (Project MUSE), Johns Hopkins University Press. Table of Contents, Northeast African Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, 2002. https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/11522.82

- National Security Agency (NSA). Cryptologic Histories: "The Cold War III: The Turbulent 1970s." https://www.nsa.gov/portals/75/documents/news-features/declassified-documents/cryptologic-histories/cold_war_iii.pdf.29

- Notre Dame Journal of Legislation. Article on Mercenaries and Neutrality Act. https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1430&context=jleg.83

- NVDatabase (Global Nonviolent Action Database), Swarthmore College. "Sudanese bring down dictator Abbud (October Revolution), 1964." https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/sudanese-bring-down-dictator-abbud-october-revolution-1964.50

- Oxford Reference. "Abboud, Ibrahim." A Dictionary of Contemporary World History. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095343251.19

- Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. "Civil-Military Relations in Sudan." https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1940.4

- PaanLuel Wël blog. "Book Review: The First Sudanese Civil War..." https://paanluelwel.com/2011/08/24/book-review-the-first-sudanese-civil-war-africans-arabs-and-israelis-in-the-southern-sudan-1955-1972/.84 (Also see WordPress version 85).

- PBS Frontline/World. "Sudan: The Quick and the Terrible - Facts & Stats." https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/sudan/facts.html.86

- Poggo, Scopas S. "General Ibrahim Abboud's Military Administration in the Sudan, 1958–1964: Implementation of the Programs of Islamization and Arabization in the Southern Sudan." Northeast African Studies, n.s., vol. 9, no. 1, 2002, n the Southern Sudan, 1955-1972*. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009..22

- Poggo, Scopas S. "The Origins and Culture of Blacksmiths in Kuku Society of the Sudan, 1797-1955." Journal of African Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 2, 2006, pp. 169-186..69

- Poggo, Scopas S. "The Politics of Liberation in the Southern Sudan 1967–1972: The Role of Israel, African Heads of State, and Foreign Mercenaries." The Uganda Journal, vol. 47, November 2001, pp. 34-48..55

- ProQuest. Entry for Poggo's article on Abboud. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/general-ibrahim-abbouds-military-administration/docview/232428487/se-2.88

- Refworld (UNHCR). "Sudan: Chronology of Events January 1994 - February 1995." Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, 1 March 1995. https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/irbc/1995/en/94326.56

- ResearchGate. Entry for Poggo's article on Abboud. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236695716_General_Ibrahim_Abboud's_Military_Administration_in_the_Sudan_1958-1964_Implementation_of_the_Programs_of_Islamization_and_Arabization_in_the_Southern_Sudan.2

- ResearchGate. "Development Economics in Sudan: The Ten-Year Economic and Social Plan 1961-1970." https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362516250_Development_Economics_in_Sudan_The_Ten-Year_Economic_and_Social_Plan_1961-1970.42

- ResearchGate. "The 1958 cotton crisis and the advent of military rule in Sudan." Journal of Eastern African Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, 2022, pp. 1-20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365331070_The_1958_cotton_crisis_and_the_advent_of_military_rule_in_Sudan.13

- Rescue South Sudan. "Sudan Timeline of Events." https://www.rescuesouthsudan.org/sudan-timeline-of-events/.52

- SAHistory.org.za. PDF of The First Sudanese Civil War by Scopas S. Poggo. https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files/scopas_s._poggo_the_first_sudanese_civil_war_afbook4you.pdf.55

- San Jose State University, Dept. of Economics. "The Economy and Economic History of Sudan." https://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/sudan.htm.89

- Small Arms Survey. "Sudan Uprising: Popular Struggles, Elite Compromises, and Revolution Betrayed." HSBA Report. https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/HSBA-Report-Sudan-Uprising_0.pdf.90

- Sudan Tribune. "Remembering the Glorious October 21st Revolution." Sudan Tribune, 21 October 2013. https://sudantribune.com/article51465/.57

- Sudan Tribune. "The Sudanese October 21st Revolution 1964." Sudan Tribune, 21 October 2016. https://sudantribune.com/article58846/.58

- Tandfonline. "Sudanese youth political activism and the ecology of the December revolution." Information, Communication & Society, 2022. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2072754.51

- Taha, Mahmoud Mohamed. (1973). (Referenced in 51, full citation needed).

- The New Order Wiki (TNO Wiki). "Ibrahim Abboud." https://tno.wiki.gg/wiki/Ibrahim_Abboud.18

- TIME Magazine. "Sudan: Bringing Down Father." TIME, 6 November 1964. https://time.com/archive/6814109/sudan-bringing-down-father/.12

- United Nations. Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. 1997. (Referenced in 35).

- University of Central Arkansas, Political Science. "Republic of Sudan (1956-present)." DADM Project. https://uca.edu/politicalscience/home/research-projects/dadm-project/sub-saharan-africa-region/70-republic-of-sudan-1956-present/.21

- US Department of State, Archive. Background Note: Sudan (2001). https://2009-2017.state.gov/outofdate/bgn/sudan/18720.htm.91

- US Department of State, Archive. Background Note: Sudan (2005). https://2009-2017.state.gov/outofdate/bgn/sudan/47092.htm.92

- US Department of State, Office of the Historian. "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Africa, Volume XIV - 43. Special National Intelligence Estimate." Document SNIE 72.1-59. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v14/d43.25

- US Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC). Report ADA151734 (Study on military coups in Africa). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA151734.pdf.93

- University of San Francisco Repository. Thesis on South Sudan's Civil War. https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2437&context=thes.94

- WeAspire. "The 1959 Agreement 'for the full utilization of the Nile waters': The crux of the problem in the Nile Basin water use." https://www.weaspire.info/the-1959-agreement-for-the-full-utilization-of-the-nile-waters-the-crux-of-the-problem-in-the-nile-basin-water-use/.35

- White Rose Etheses Online. PhD Thesis on Political Economy of Sudan (1956-1985). https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/294/1/uk_bl_ethos_392278.pdf.95

- Wikidata. Entry for Ibrahim Abboud. https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q319216.20

- Wikipedia contributors. "First Sudanese Civil War." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Sudanese_Civil_War.65

- Wikipedia contributors. "History of Sudan." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Sudan.23

- Wikipedia contributors. "Ibrahim Abboud." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified 16 February 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibrahim_Abboud.5

- Wikipedia contributors. "Philip Agee." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Agee.26

- Wikipedia contributors. "Republic of Sudan (1956–1969)." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified 23 March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Sudan_(1956%E2%80%931969.9

- Wikipedia contributors. "Sudanese revolution." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sudanese_revolution.62

- Wikipedia contributors. "1959 Sudanese coup attempt." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1959_Sudanese_coup_attempt.32

- Wikipedia contributors. "Water politics in the Nile Basin." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_politics_in_the_Nile_Basin.33

- World Bank Documents & Reports. "Sudan - Roseires Irrigation Project." Memorandum & Recommendation of the President, P253, 7 June 1961. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/427901468164053795.47

- World Bank Documents & Reports. "Sudan - Roseires Irrigation Project." Report, October 1958 mission mentioned. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/531561468121768835/pdf/Sudan-Roseires-Irrigation-Project.pdf.38

- World Bank Documents & Reports. Sudan Country Data Sheet (c. 2002). https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/440091468777571140/pdf/multi0page.pdf.96

- YouTube. Video biography of Ibrahim Abboud (summary based on transcript). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aM0cIf08n-I.60

- Young, Alden. Transforming Sudan: Decolonization, Economic Development, and State Formation. Cambridge University Press, 2017..15

- Young, John. "Sudan Uprising: Popular Struggles, Elite Compromises, and Revolution Betrayed." HSBA Report, Small Arms Survey. (Likely source of 90).

12. Appendix

Table A1: Detailed Timeline of Ibrahim Abboud's Life and Key Sudanese Events (1900-1983)

| Year | Event | Relevant Snippets |

| 1900 | Oct 26: Ibrahim Abboud born in Mohammed-Gol, near Suakin. | |

| ~1918 | Educated at Gordon Memorial College (Engineering) and Military College, Khartoum. | |

| 1918 | Commissioned into the Egyptian Army. | |

| 1925 | Transferred to the newly formed Sudan Defence Force (SDF). | |

| WWII | Served with SDF in Eritrea, Ethiopia; with British Army in North Africa. | |

| Post-WWII | Commanded Camel Corps. | |

| 1949 | Appointed Commander of the Sudan Defence Force. | |

| 1953 | Anglo-Egyptian agreement grants Sudan path to self-government/independence. | |

| 1954 | Appointed Assistant Commander-in-Chief; promoted to General. | |

| 1955 | Aug: Torit Mutiny in Southern Sudan; start of First Sudanese Civil War. | |

| 1956 | Jan 1: Sudan declares independence. Abboud appointed Commander-in-Chief of Sudanese Armed Forces. | |

| 1956-1958 | Period of unstable civilian parliamentary rule (Azhari, then Khalil govts); economic problems (cotton crisis); Southern conflict. | |

| 1957 | Government takes over mission schools in the South. | |

| 1958 | Nov 16-17: Abboud leads bloodless military coup, overthrows Khalil government. | |

| 1958 | Nov 18: Supreme Council of Armed Forces formed; Abboud becomes Prime Minister (Nov 19). | |

| 1958-1959 | Abboud regime lowers cotton prices, sells surplus, easing financial crisis. | |

| 1959 | Mar: Abboud dismisses and reconstitutes Supreme Council. | |

| 1959 | Nov 8: Nile Waters Agreement signed with Egypt. | |

| 1959 | Nov 9-10: Failed military coup attempt against Abboud; leaders later executed (Dec 20). | |

| 1960 | Friday imposed as official weekly day of rest in the South. | |

| 1961 | Ten-Year Economic and Social Development Plan launched. | |

| 1961 | Abboud visits US White House, meets President Kennedy. | |

| 1962 | Managil Extension of Gezira Scheme completed. | |

| 1962 | Missionaries Act passed; expulsion of foreign Christian missionaries from South intensifies. | |

| 1962 | Oct: Widespread strike in Southern schools against Arabization policies. | |

| 1963 | Sep: Anya-Nya rebellion intensifies in Equatoria and Upper Nile provinces. | |

| 1964 | Aug: Abboud establishes commission to study Southern problem. | |

| 1964 | Oct 21: KUSU meeting on South broken up by police; student Ahmed Al-Qurashi killed. | |

| 1964 | Oct 22-25: Mass demonstrations, formation of United National Front, general strike called. | |

| 1964 | Oct 26: Abboud dissolves government and Supreme Council. | |

| 1964 | Oct 30: Abboud ceases to be Prime Minister (replaced by Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa). | |

| 1964 | Nov 15/16: Abboud resigns as President/Head of State, ending first military rule. | |

| Post-1964 | Abboud lives in retirement, including some years in England. | |

| 1983 | Sep 8: Ibrahim Abboud dies in Khartoum. |