Abbas II (1874-1943)

Khedive of Egypt 1892-1914. Attempted to run independently of British influence. During WWI he sided with Turkey and was deposed when the British made Egypt into a protectorate.

Abstract

This article examines the tumultuous reign of Abbas Hilmi II, the last Khedive of Egypt and Sudan (1892-1914). Ascending the throne amidst entrenched British occupation, Abbas II navigated a complex political landscape, marked by his persistent, albeit often frustrated, attempts to assert Khedivial authority against formidable British agents like Lord Cromer and Lord Kitchener. Analyzing primary source material, including the Abbas Hilmi II Papers and contemporary accounts, this study traces Abbas II's evolving relationship with Egyptian nationalism, his patronage of development projects like the Aswan Low Dam, and the critical incidents, such as the 1894 Frontier Incident and the 1906 Dinshaway Incident, that defined his era.

The paper argues that Abbas II's reign exemplifies the inherent contradictions of ruling under colonial dominance, where efforts towards modernization and national assertion were constantly constrained by imperial interests.

His deposition in 1914 at the outbreak of World War I marked the formal end of Ottoman suzerainty and the transition to a British Protectorate, highlighting the geopolitical forces that ultimately shaped Egypt's destiny to the present day. The analysis extends to his long exile and explores the causal links between the dynamics of his reign and subsequent developments in modern Egyptian history and patterns of foreign intervention in the Middle East.

1. Introduction: The Khedivate in the Shadow of Empire

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Egypt occupied a peculiar position within the international order.

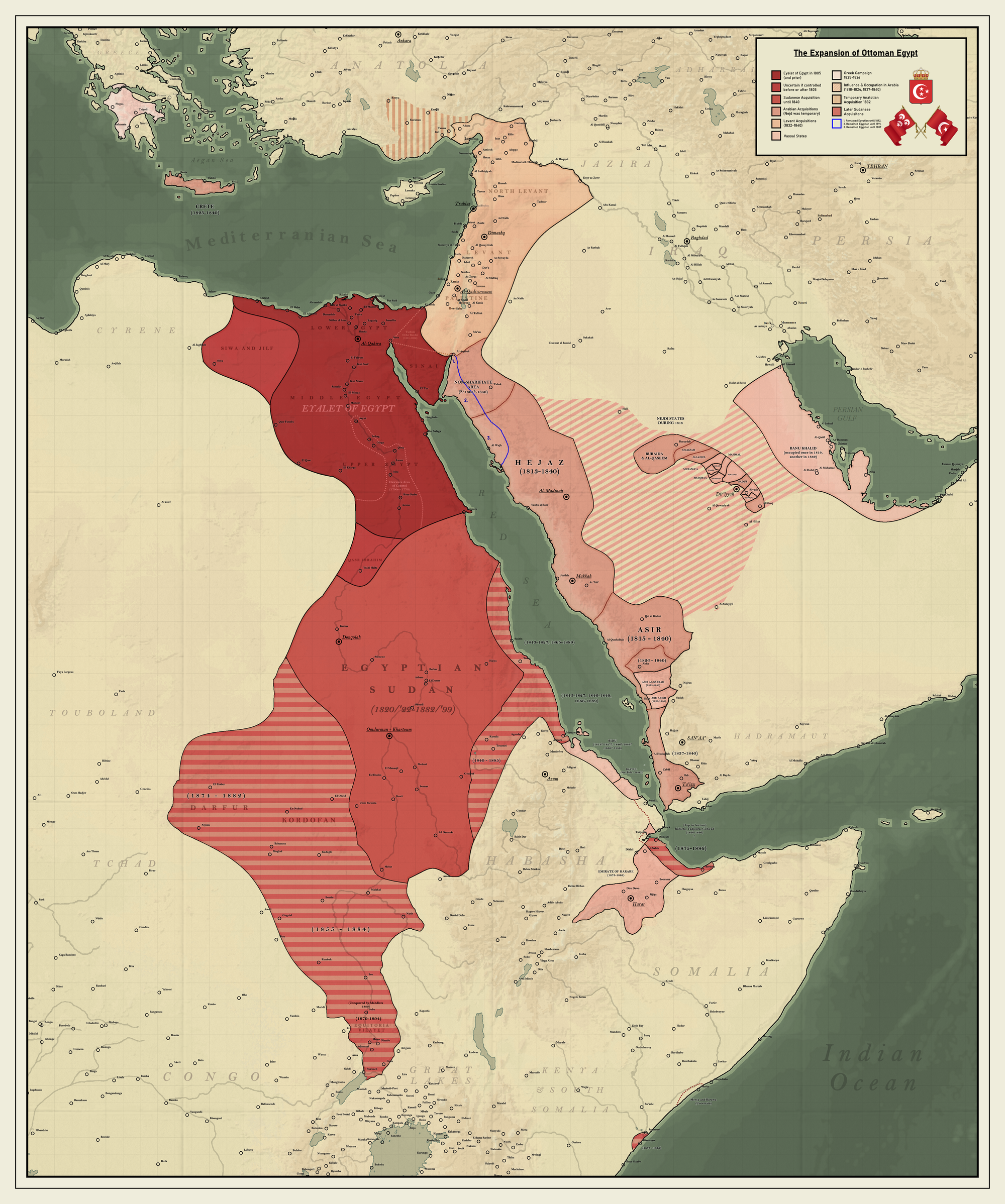

Nominally, it remained an autonomous Khedivate within the Ottoman Empire, a status established by the ambitious Muhammad Ali Pasha earlier in the nineteenth century. However, the reality on the ground was starkly different. Since 1882, Egypt had been under a de facto British military occupation, initiated ostensibly to restore 'financial stability' following the perceived mismanagement of Khedive Isma'il and to quell the nationalist Urabi revolt. What was initially presented as a temporary measure had, by the 1890s, solidified into an enduring system of indirect British control, often termed a "veiled protectorate".

Into this complex and contradictory political environment stepped Abbas Hilmi II. The great-great-grandson of Muhammad Ali, Abbas II succeeded his father, Khedive Tewfik Pasha, in January 1892. He inherited the title of Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, a position theoretically subordinate only to the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul but practically overshadowed by the immense power wielded by whomsoever was the British Agent and Consul-General in Cairo at the time, most notably Lord Cromer during the majority of Abbas's reign.

This paper contends that the reign of Abbas II, spanning from 8 January 1892 to his deposition on 19 December 1914, was fundamentally defined by a persistent, though ultimately unsuccessful, struggle to reconcile the Khedivial aspiration for genuine sovereignty with the unyielding reality of British imperial control.

His actions, which vacillated between direct confrontation and pragmatic cooperation with the occupying power, reflected not only his personal ambitions and character but also the growing force of Egyptian nationalism. This complex interplay shaped the key events of his rule and ultimately led to his removal from power amidst the seismic geopolitical shifts triggered by the outbreak of World War I.

The historiography of Abbas II's reign has long been influenced by the powerful, often critical, narrative presented by Lord Cromer himself in his work Abbas II, published in 1915 shortly after the Khedive's deposition. Cromer, most sources agree, hated Abbas, and portrayed him as an obstructionist figure attempting to undermine beneficial British influence. This colonialist perspective must be balanced against the counter-narrative offered by Abbas II in his own memoirs, dictated during his exile, and, crucially, by the extensive archival collection of his personal and official papers housed at Durham University. These sources, increasingly utilized by historians, allow for a fuller analysis that moves beyond simplistic binaries and acknowledges the complexities of Abbas II's position and the broader political, social, and economic currents of the era. This study aims to contribute to this reassessment by examining the key phases and events of Abbas II's rule, his relationship with nationalism, his role in Egypt's development, and the circumstances of his downfall, placing his reign within the broader context of modern Egyptian history and the dynamics of imperialism.

Structure and Scope

The paper will proceed chronologically and thematically. It will first examine Abbas II's formative years and accession, followed by an analysis of his early attempts to assert Khedivial authority against British power, particularly against Lord Cromer and Lord Kitchener. It will then explore the period marked by significant crises, notably the Dinshaway Incident, and shifting alliances under Cromer's successor, Sir Eldon Gorst. The subsequent section will detail the final confrontation with the returned Lord Kitchener and the events leading to Abbas II's deposition in 1914. The paper will then consider his long years in exile and conclude by analyzing the legacy of his reign and drawing parallels with subsequent developments in modern Egyptian history and the wider Middle East.

2. Formative Years and Accession (1874-1892)

Abbas Hilmi II was born on 14 July 1874, either in Alexandria or Cairo, into the heart of the ruling Muhammad Ali Dynasty. As the eldest son of Khedive Muhammad Tewfik Pasha and Princess Emina Ilhamy, he was destined for a life of privilege and political significance. His lineage traced directly back to Muhammad Ali Pasha, the dynasty's founder. An elaborate ceremonial circumcision held in 1887 for Abbas and his younger brother, Mohammed Ali Tewfik, lasting three weeks, underscored the traditional pomp associated with the Khedivial family.

His education was cosmopolitan, reflecting both Egyptian traditions and the increasing European influence of the era. He received early tutoring from private instructors at the Princes' School established by his father near Abdin Palace in Cairo. This included instruction from European, Arab, and Ottoman masters. A visit to the United Kingdom as a boy, coupled with the presence of British tutors and a governess who taught him English in Cairo, provided early exposure to British culture and language. His formal education continued in Europe, first at a school in Lausanne, Switzerland, followed by the Haxius School in Geneva (from age twelve), and culminating at the prestigious Theresianum academy in Vienna. This extensive European schooling equipped him with fluency not only in his native Arabic and Ottoman Turkish but also conversational proficiency in English, French, and German. His training also included military instruction under an American officer in the Egyptian army.

This sophisticated, multilingual, and European-focused education, while intended to prepare him for rule in a modernizing world, inadvertently set the stage for future conflict. It provided him with the tools to engage with European powers on their own terms but likely also fostered a sense of self-reliance and perhaps resentment towards the notion of needing British tutelage, distinguishing him from predecessors who might have felt less equipped to challenge European dominance. His multifaceted upbringing placed him at the intersection of Egyptian, Ottoman, and European cultural and political spheres.

His ascent to power was abrupt. While still pursuing his studies in Vienna, his father, Khedive Tewfik, died suddenly. Abbas II was recalled urgently to assume the throne of the Khedivate of Egypt and Sudan on 8 January 1892. At seventeen or eighteen years old (sources differ slightly on his exact age relative to the Islamic calendar used for succession), he was barely of the legal age required for succession. He returned to Egypt, arriving first in Alexandria before proceeding to Cairo to begin his reign, inheriting a position defined by the complex legacy of his dynasty and the pervasive reality of British occupation.

3. Asserting Khedivial Authority against Imperial Power (1892-1906)

From the outset of his reign, the young Khedive Abbas II demonstrated a reluctance to passively accept the subordinate role envisioned for him by the British occupiers. Driven by a desire to be a "real Khedive" rather than a mere figurehead, he chafed under the tutelage of the formidable British Agent and Consul-General, Evelyn Baring, Lord Cromer. Initially, Abbas surrounded himself with European advisors known for their opposition to the British presence and sought to cultivate closer ties with the Egyptian populace while resisting British policies.

His determination to assert Khedivial prerogative quickly led to direct confrontations with British authority. The first major crisis erupted in January 1893, just a year into his reign. Abbas dismissed the incumbent Prime Minister, Mustafa Fahmi Pasha, who was perceived as loyal to the British, and attempted to install his own, more nationalistic nominee.

This move was swiftly countered by Lord Cromer, who, with the backing of the British Foreign Secretary Lord Rosebery, informed Abbas that he was obligated to consult the British representative on cabinet appointments. The Khedive's attempt was frustrated, and Mustafa Fahmi eventually returned to office, demonstrating the stark limits on Abbas's executive power.

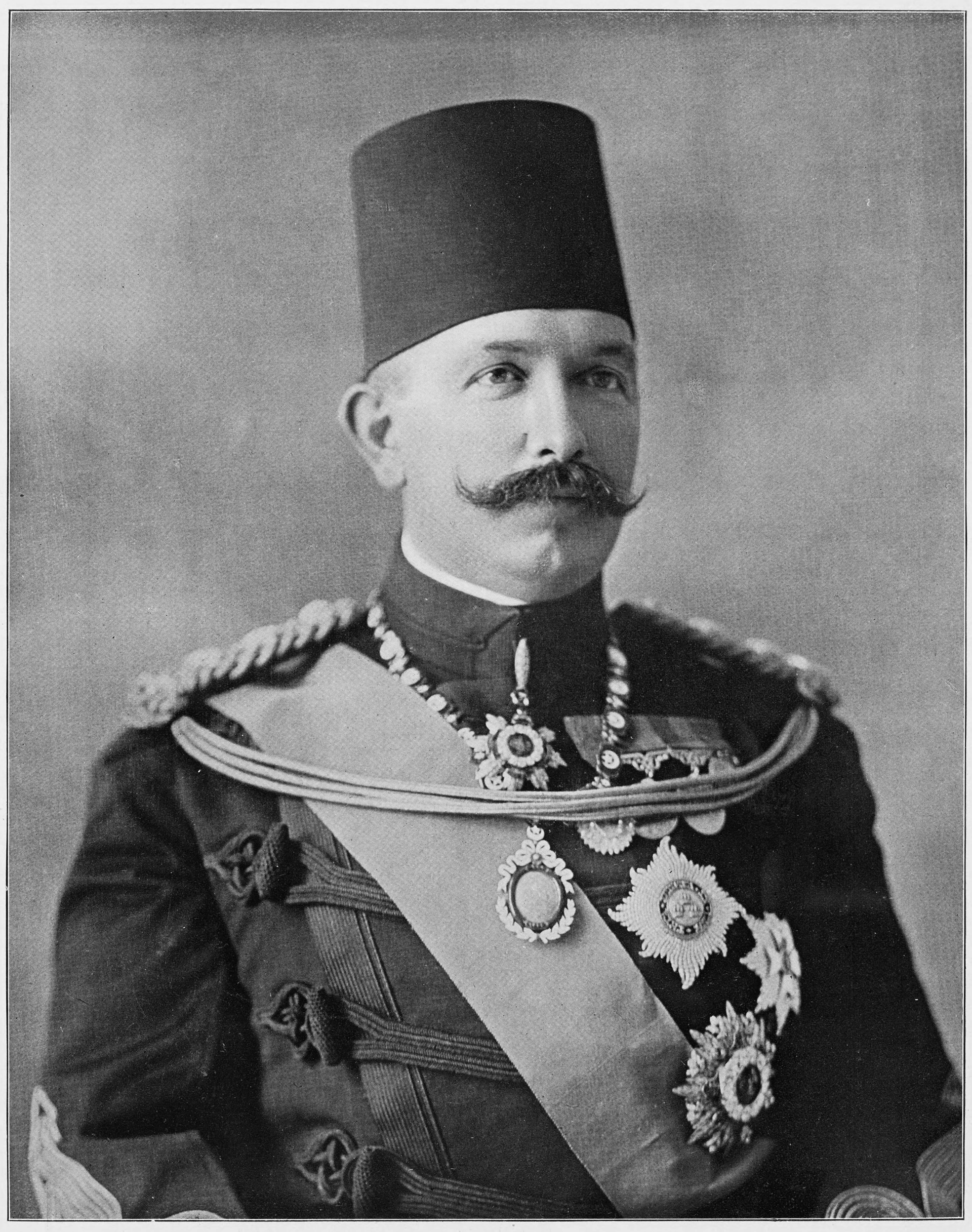

A second, perhaps more significant, clash occurred in January 1894, known as the "Frontier Incident". While inspecting Egyptian army units stationed near the southern frontier at Wadi Halfa (with Sudan still largely under Mahdist control), Abbas made public remarks disparaging the competence and discipline of troops commanded by British officers.

This criticism was seen as a direct challenge to the authority of the British Sirdar (Commander-in-Chief) of the Egyptian Army, Sir Herbert Kitchener. Kitchener immediately threatened to resign, along with other British officers, demanding the dismissal of a nationalist under-secretary of war appointed by Abbas and a formal apology from the Khedive. Once again, Cromer intervened forcefully, compelling Abbas to retract his criticisms publicly and concede to Kitchener's demands.

This incident was far more than a personal dispute; it represented a struggle over the control and symbolism of the military, a key instrument of state power and sovereignty.

The army was not only crucial for maintaining internal order and defending borders (or expanding them, as in the impending Sudan campaign) but also a potent symbol of national identity.

Abbas's challenge, however brief, touched a raw nerve, questioning British leadership in the very institution underpinning their occupation. The swift and decisive British reaction, culminating in the Khedive's public humiliation, served as a stark reminder of where ultimate authority lay.

It likely impressed upon Abbas the futility of direct military confrontation and encouraged a shift towards more indirect methods of resistance, such as supporting the nationalist press.

Despite these setbacks, Abbas continued to align himself with the burgeoning Egyptian nationalist movement, at least initially. His early anti-British posture earned him considerable popularity among Egyptians, who saw in him a potential champion against the occupation.

He provided financial support to the pan-Islamic and anti-British newspaper Al-Mu'ayyad and fostered a relationship with the prominent nationalist leader Mustafa Kamel. Kamel, in turn, sought to rally national sentiment around the Khedive, founding the influential newspaper Al-Liwa' in 1900 with this aim.

The era saw a flourishing of the press, with publications like Al-Hilal (founded 1892) and Al-Jarida (founded 1907) contributing to political discourse.

Parallel to these political maneuvers, Abbas II's reign saw significant internal developments, often undertaken with British oversight or approval, reflecting a complex interplay between Khedivial initiative, nationalist aspirations, and imperial objectives.

The reconquest of Sudan (1896-1898), commanded by Kitchener, was largely financed and manned by Egypt. While ostensibly restoring Egyptian authority, the campaign culminated in the 1899 Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement, which established nominally joint rule but effectively solidified British control over Sudan. This venture, while expanding the territory under nominal Khedivial authority, simultaneously highlighted Egypt's subordinate role and the use of its resources for British imperial ends.

A cornerstone project of the era was the construction of the Aswan Low Dam. Initiated around 1898-1899 and completed in 1902, it was a major feat of engineering designed to regulate the Nile's floodwaters and expand irrigated agriculture, particularly for cotton cultivation. Abbas II gave his formal approval to this and other substantial irrigation works.

Table 2: Aswan Low Dam - Key Facts (Initial Construction & Heightenings)

| Feature | Details | Source(s) |

| Project Name | Aswan Low Dam (or Old Aswan Dam) | |

| Location | Nile River, Aswan, Egypt (at the First Cataract) | |

| Type | Gravity masonry buttress dam | |

| Designer | Sir William Willcocks | |

| Main Contractor | John Aird & Co. | |

| Initial Construction | 1898/1899 - 1902 | |

| Opened | 10 December 1902 | |

| Khedive during Const. | Abbas Hilmi II | |

| Initial Capacity | ~1 billion cubic meters (filled 1902-1903) | |

| Initial Height Limit | Imposed due to concerns for Philae Temple | |

| First Heightening | 1907 - 1912 (raised 5 meters) | |

| Capacity after 1st | ~2.5 billion cubic meters | |

| Second Heightening | 1929 - 1933 (raised 9 meters) | |

| Capacity after 2nd | ~5.0 - 5.3 billion cubic meters | |

| Cost | Specific cost data for the Low Dam construction/heightenings is not detailed in the provided material. |

The dam, along with other infrastructure projects like the extension of railway lines connecting major cities, the construction of vital agricultural roads (Cairo-Alexandria, Helwan-Cairo), and the building of numerous bridges across the Nile in Cairo, represented tangible modernization efforts.

These projects served multiple purposes: they facilitated economic activity, particularly the lucrative cotton trade; they enhanced the state's administrative reach; and they visually symbolized progress under the Khedive's rule. However, they simultaneously deepened Egypt's integration into the British-dominated global economy and improved the logistical capabilities of the occupying power.

The development strategy thus embodied the inherent ambiguity of Abbas's position – promoting Egyptian progress within a framework largely defined and controlled by British interests. Cromer's emphasis on material progress and sound finances found expression in these projects, which Abbas approved.

Economically and socially, the reign also saw the establishment of key financial institutions like the National Bank of Egypt (1898) and the Egyptian Arab Land Bank (1902), alongside initiatives like the Agricultural Society (1898).Abbas displayed a personal interest in agricultural science, establishing model farms. Reforms were pursued in the justice system for Egyptians, taxation was reduced, and education saw advancements with the dispatch of scientific missions abroad and the initiation of the Ahlia University project (later Cairo University).

Social initiatives included the Islamic Charitable Association (1892), and administrative reforms included the establishment of a Legislative Assembly and a reforming law for Al-Azhar University. The discovery of oil in 1912 added another dimension to Egypt's resource landscape.

However, the period after the initial confrontations saw a pragmatic shift in Abbas's approach. A second visit to Britain in 1900 included statements praising British contributions to Egypt and expressing a readiness to cooperate with British officials. He gave formal approval to various British-led initiatives.

The appointment of Alfred Mitchell-Innes as Under-Secretary for Finance in 1899 also signaled a degree of accommodation. This apparent détente was significantly influenced by the changing international landscape. The signing of the Entente Cordiale between Britain and France in 1904 effectively removed France as a potential counterweight to British power in Egypt, granting Britain a free hand.

This development weakened Abbas's diplomatic leverage and reportedly deflated the hopes of his nationalist ally, Mustafa Kamel, making the Khedive more inclined towards cooperation with Cromer. This phase highlights the Khedive's tactical flexibility, adjusting his strategy when direct confrontation proved ineffective or international circumstances shifted against him.

4. Navigating Crises and Shifting Alliances (1906-1912)

The period following the Entente Cordiale saw a complex interplay of nationalist mobilization, British responses, and Khedivial maneuvering, profoundly shaped by the watershed event of the Dinshaway Incident.

In June 1906, a hunting party of British officers near the village of Dinshaway in the Nile Delta sparked a confrontation with local peasants. The villagers, protective of their pigeons (a source of livelihood), became enraged when the officers began shooting and a fire broke out, allegedly caused by the gunfire, destroying a threshing floor.

In the ensuing scuffle, several villagers were injured, including a woman (who later died according to some accounts), and officers were attacked with sticks (nabouts) and bricks. One officer attempting to run back to camp collapsed and died, likely from a combination of concussion sustained in the fight and sunstroke. Another villager found near the dead officer was subsequently killed by arriving British soldiers.

The British authorities, perceiving the attack as premeditated, responded with swift and brutal severity. A Special Tribunal, established under a decree allowing it to bypass the regular penal code, tried 52 villagers.

The trial was summary, and the sentences, delivered just days after the incident, were exemplary: four men were condemned to death by hanging, others sentenced to penal servitude for life or long prison terms, and several subjected to public flogging.

The executions and floggings were carried out publicly in Dinshaway itself, despite public executions having been previously stopped. British officials, including the acting Consul-General Findlay (Cromer was absent), resisted suggestions from London to review the death sentences before execution, arguing delay would cause dangerous excitement.

The Dinshaway Incident became a pivotal moment in the history of Egyptian nationalism.

The perceived injustice and the sheer brutality of the official response sent shockwaves through Egypt and garnered criticism even in Britain. It provided powerful, visceral evidence for nationalist narratives portraying the British occupation as oppressive and contemptuous of Egyptian life.

The incident transformed nationalism from a largely elite discourse into a potent popular force, resonating deeply with the peasantry and generating widespread support for resistance. The villagers became martyrs, immortalized in popular songs and poems. Mustafa Kamel and his National Party effectively utilized the outrage to galvanize support. The affair irrevocably damaged British prestige and claims of benevolent rule, ultimately contributing to Lord Cromer's retirement in May 1907. Lord Cromer himself later acknowledged the sentences were "unduly severe". The incident also had sectarian undertones, as the head of the special tribunal was Boutros Ghali Pasha, a prominent Coptic Christian politician, leading to resentment against him within parts of the nationalist movement.

Khedive Abbas II's position during this crisis was complex. Having previously shifted towards cooperation with Cromer after the Entente Cordiale, he found himself somewhat distanced from the peak of nationalist fervor.

When nationalists, likely energized by Dinshaway, demanded constitutional government in 1906, Abbas, described as "reconciled with the British," rejected these demands. Yet, the following year, he consented to the formal establishment of Mustafa Kamel's National Party, possibly as a strategic move to counterbalance the more moderate, British-favored Ummah Party, suggesting an attempt to navigate and potentially manage the powerful nationalist currents rather than fully commit to them.

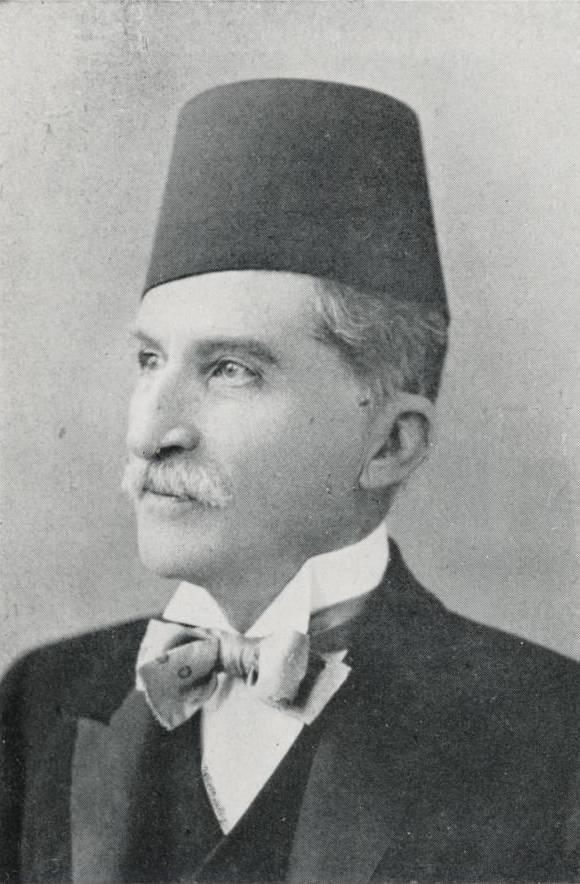

Cromer's successor, Sir Eldon Gorst (1907-1911), represented a brief departure from Cromer's autocratic style. Recognizing the need for a different approach after Dinshaway, Gorst pursued a policy of conciliation. He cultivated an excellent working relationship with Khedive Abbas II, reached an understanding with him, and sought to reduce the size and influence of the British administrative establishment while granting more effective authority to Egyptian political institutions. This "Gorst Experiment" saw cooperation between the Khedive and the British representative in appointing Egyptian-led cabinets, including that of Boutros Ghali in 1908 and Muhammad Sa'id Pasha in 1910. Together, they also worked to check the growing power of the more radical National Party. This interlude represented an attempt at a form of shared governance, moving away from direct confrontation.

However, this period of relative calm was shattered by the assassination of Prime Minister Boutros Ghali Pasha on 20 February 1910 (he died the following day). Ghali, the first Coptic Christian Prime Minister of Egypt, was shot by Ibrahim Nassif al-Wardani, a young, European-educated pharmacist associated with Mustafa Kamel's Watani Party.

The assassination was explicitly linked to Ghali's perceived pro-British stance and his role in the Dinshaway tribunal. This act, the first public assassination of a senior Egyptian statesman in over a century, dramatically highlighted the radicalization within the nationalist movement and the intense political polarization of the era. It dealt a severe blow to Gorst's conciliatory policy, demonstrating the deep-seated opposition that moderate or collaborationist figures faced.

The assassination likely reinforced British hardliners' views that conciliation was futile. Furthermore, Gorst's policy faced challenges from a resistant British staff in Egypt and political pressures from London, and his untimely death in 1911 cut short the experiment before its potential could be fully tested.

5. The Final Confrontation and Deposition (1912-1914)

The death of Sir Eldon Gorst and the subsequent appointment of Field Marshal Lord Kitchener as British Agent and Consul-General in 1911 (taking office 1912) signaled the end of the brief interlude of conciliation and marked a return to a more brutal, autocratic style of British rule. This inevitably reignited the long-standing antagonism between the Khedive and the British representative.

Kitchener, the formidable Sirdar whom Abbas had publicly criticized back in 1894, harboured a deep distrust and dislike for Abbas. Relations between the two deteriorated rapidly. Kitchener frequently complained about "that wicked little Khedive" and openly expressed his desire to see him deposed.

Kitchener moved decisively to consolidate British control and marginalize opposition. He systematically targeted the leaders of the National Party, subjecting them to exile or imprisonment. Simultaneously, he took steps to curtail Khedive Abbas's remaining authority.

The collision course set two decades earlier during the Frontier Incident seemed destined for a final, decisive encounter. Kitchener's personality and methods left little space for the kind of maneuvering and balancing Abbas had previously employed, effectively pushing the Khedive further into opposition.

Despite his authoritarian approach, Kitchener's tenure was not devoid of reforms. The Organic Law of 1913 introduced a new Legislative Assembly with expanded, albeit still limited, powers. This body, while falling short of nationalist demands for full parliamentary government, inadvertently served as a training ground for future nationalist leaders who would dominate the post-World War I era.

Kitchener also implemented measures aimed at improving irrigation and protecting peasant land tenure, particularly safeguarding smallholdings from seizure for debt. These reforms could be interpreted in several ways: as genuine attempts at administrative improvement, as efforts to cultivate popular support among the peasantry thereby bypassing the Khedive and the urban nationalist elite, or as measures to enhance Egypt's economic productivity for the benefit of the Empire.

The outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914 dramatically altered the political calculus. Khedive Abbas II was in Constantinople convalescing after surviving an assassination attempt in July. When the Ottoman Empire formally entered the war on the side of the Central Powers in early November 1914, Abbas, still outside Egypt, faced a critical choice. He chose to align himself with his nominal sovereign, the Ottoman Sultan, and against the British occupying power. He issued appeals calling on Egyptians and Sudanese to support the Central Powers and fight the British. Reports suggest he even proposed leading an Ottoman attack on the strategically vital Suez Canal. By not returning to Egypt promptly, he was accused by the British of effectively deserting his country.

This decision, whether motivated by loyalty to the Caliphate, nationalist conviction, resentment towards the British, or a strategic gamble on a German-Ottoman victory, provided the British with the ultimate justification to remove him. In the context of a global war, Britain could not tolerate a potentially hostile ruler in Egypt, a country crucial for imperial communications (Suez Canal) and as a military base. Abbas's alignment with the enemy sealed his fate, offering Kitchener and the British government the opportunity they likely desired.

On 18 December 1914, Great Britain formally declared Egypt a British Protectorate, severing the centuries-old, albeit largely symbolic, tie to the Ottoman Empire.The following day, 19 December 1914, Khedive Abbas II was officially deposed.

The Khedivate, as a ruling title and institution under Ottoman suzerainty, ceased to exist.

The British moved quickly to install a more compliant ruler. They bypassed Abbas's direct line and offered the throne, now elevated to the title of Sultan, to his uncle, Hussein Kamel.

Hussein Kamel was considered more reliably pro-British. Interestingly, his son, Prince Kamal el-Din Hussein, reportedly refused the succession, possibly out of loyalty to his deposed brother-in-law Abbas or due to principled opposition to the British Protectorate.

Upon Hussein Kamel's death in 1917, the Sultanate passed to another of Abbas's uncles, Ahmad Fuad (Fuad I), who would later become King.

The deposition of Abbas II thus not only ended his personal rule but also marked a fundamental shift in Egypt's constitutional status and dynastic succession, firmly placing the country under direct British imperial control for the duration of the war and beyond.

6. The Long Exile (1914-1944)

Deposed while travelling abroad, Abbas Hilmi II spent the remaining three decades of his life in exile, permanently barred from returning to Egypt by the British and the successor regimes they installed.His primary place of residence became Switzerland, particularly Geneva and Zurich, although he also spent time in other European capitals like Paris and maintained connections with Turkey.

His exile was marked by significant personal and financial challenges. The new Egyptian administration under Sultan Hussein Kamel moved swiftly to sequester Abbas's extensive properties, estates, palaces, and business interests in Egypt and Sudan. Restrictive orders forbade financial contributions being sent to him and stripped him of the right to pursue legal action within Egyptian courts. His personal archives, now housed at Durham University, contain considerable material documenting his persistent efforts throughout his exile to recover his sequestered assets and manage his remaining finances.Sensationalist contemporary accounts, such as one based on the recollections of his former aide-de-camp Kelemen Arvay, paint a picture of financial difficulties and vulnerability to manipulation by companions, like the French dancer Andrée de Lusange, during his exile.While such accounts require critical assessment, they suggest the personal and financial precariousness that accompanied his loss of power.

Despite his deposition and financial constraints, Abbas II did not entirely withdraw from the political arena, albeit his influence was significantly diminished. During World War I, he remained a figure of interest to the Central Powers. He attempted to maintain relevance by engaging with Egyptian nationalist circles active in Europe, particularly student groups in Germany and Switzerland. Evidence from his archives indicates he provided funding to some of these groups and individuals, maintaining networks of agents to gather information both about exile activities and the situation within Egypt. His motivations were likely mixed: a genuine desire for Egyptian independence, combined with personal and dynastic ambitions for a potential restoration to power.

A significant part of his activity in exile involved shaping his own historical narrative and legacy. He authored The Anglo-Egyptian Settlement, published in 1930, which presented his views on the relationship between Egypt and Britain. He also dictated his memoirs, published posthumously, offering a detailed counter-perspective to the critical accounts penned by British officials like Lord Cromer. These writings represent a deliberate effort to justify his actions, critique British imperialism, and secure a more favourable place in history. Even the protracted struggle over his sequestered properties can be viewed as a political act, implicitly challenging the legitimacy of the regime that had ousted him and seized his wealth.

Politically, however, his exclusion from Egypt proved permanent. Egypt was declared nominally independent in 1922 and transformed into a Kingdom under his uncle, Fuad I.A Royal Edict issued that year specifically barred Abbas II from the line of succession, although it explicitly stated this exclusion did not apply to his sons and their progeny. Facing this irreversible reality, Abbas II formally abdicated any remaining claim to the throne on 12 May 1931.

Abbas Hilmi II died in Geneva on 19 December 1944, at the age of 70. His death occurred exactly thirty years to the day after the formal end of his reign. He was buried in the Khedivial mausoleum, Qubbat Afandina, in Cairo.

Regarding his personal life, Abbas II married twice during his reign. His first marriage was to Ikbal Hanim in 1895; they had six children (four daughters: Princesses Emina, Attiyat-Allah, Fatheya, Lutfiya Shawket; and two sons: Prince Muhammad Abdel Moneim and Prince Abdel Kader) before divorcing in 1910.

His second marriage was to the Hungarian Marianna Török, known as Djavidan Hanem, in 1910; they divorced in 1913.

His eldest son, Prince Muhammad Abdel Moneim, would briefly serve as Chairman of the Council of Regency for the infant King Fuad II following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952.

Abbas II's grandson, Prince Abbas Hilmi (son of Muhammad Abdel Moneim), born in 1941, continues to play a role in preserving the family's legacy, notably through the Mohamed Ali Foundation, which deposited the Khedive's invaluable papers at Durham University.

The existence and increasing accessibility of these archivesrepresent perhaps the most significant aspect of Abbas II's posthumous legacy. Containing official and personal correspondence, financial records, intelligence reports, and materials in multiple languages, this collection provides an indispensable resource for scholars.

It offers a crucial counterweight to the often dominant British colonial narratives, enabling a more balanced and complex understanding of Egyptian politics, society, and economy during a critical period of transition.

The archive itself functions as a historical actor, facilitating evidence based interpretations and ensuring that the perspective of the last Khedive and his administration remains central to the ongoing historical debate.

7. Abbas II's Egypt in Modern Historical Context: Parallels and Causal Connections

The reign of Khedive Abbas II, situated at the intersection of Ottoman decline, burgeoning Egyptian nationalism, and assertive British imperialism, offers numerous parallels and causal connections to subsequent developments in modern Egyptian and Middle Eastern history.

Examining these links provides a deeper understanding of the enduring legacies of this period.

The intense focus of the British administration under Cromer and his successors on controlling Egypt's economic resources, particularly cotton, and its strategic location, exemplified by the Suez Canal, established a pattern of foreign interest driven by economic and geopolitical imperatives.

This dynamic, where external powers prioritize resource access and strategic advantage over local sovereignty, resonates throughout twentieth and twenty-first-century Middle Eastern history, most notably in relation to oil reserves.

Furthermore, large-scale development projects like the Aswan Low Dam, initiated during Abbas II's reign, while aimed at modernization, also entrenched Egypt's reliance on a specific agricultural export model (cotton) and created complex hydro-political dependencies.

The subsequent construction of the Aswan High Dam under Nasser, while fulfilling nationalist ambitions, generated significant environmental and social consequences, echoing the complex trade-offs inherent in the earlier project and highlighting themes relevant to modern debates on development, resource management, and environmental impact.

The economic structures solidified during this era, emphasizing export agriculture, contributed to long-term structural vulnerabilities in the Egyptian economy, making it susceptible to global market fluctuations and fostering dependencies that persisted long after political independence was achieved.

The core conflict of Abbas II's reign – the clash between Egyptian nationalism and British imperial control– clearly prefigures the broader anti-colonial struggles that swept across Asia and Africa in the twentieth century. Abbas II's own complex relationship with the nationalist movement – sometimes supporting it, sometimes co-opting it, sometimes opposing its demands– reflects the often-complicated interactions between traditional elites and modern mass movements under colonial rule.

Incidents like the 1906 Dinshaway affair served as powerful catalysts, transforming elite grievances into popular outrage and mobilizing mass support for the anti-colonial cause, a pattern observed in numerous other independence movements globally. The unresolved question of sovereignty during his reign laid the foundation for future conflicts.

The persistent tension between the desire for genuine independence and the constraints of British power fueled subsequent waves of nationalist struggle, including the 1919 Revolution, the negotiations leading to the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, the 1952 revolution that overthrew the monarchy, and the Suez Crisis of 1956, all of which can be viewed as attempts to achieve the full sovereignty denied during the era of occupation.

The role of the military was another critical theme with lasting repercussions. The 1894 Frontier Incident, where Abbas II challenged British command over the Egyptian army, underscored the centrality of military control to both imperial power and national sovereignty.

Although Abbas's challenge was swiftly crushed, it highlighted Egyptian resentment of foreign military domination.

The British reliance on the military to maintain the occupation reflects a common feature of colonial and interventionist policies. This early tension foreshadowed the pivotal role the Egyptian military would play in post-independence politics, culminating in the Free Officers' coup in 1952 and the subsequent decades of military influence over the state.

The deposition of Abbas II itself serves as a stark illustration of how regional political dynamics can be decisively shaped by larger global conflicts. World War I provided Britain with the pretext and perceived necessity to formalize its control over Egypt by declaring a Protectorate and removing a ruler deemed unreliable.

The war effort itself placed immense strain on Egypt, which served as a crucial base and source of manpower (primarily labor corps) and resources for the British campaign against the Ottoman Empire.

The resulting social and economic hardships, including inflation, food scarcity, unemployment, and increased disease rates, significantly aggravated existing grievances against the occupation. This wartime suffering was a direct contributing factor to the nationwide uprising known as the 1919 Revolution, demonstrating how participation in global conflicts, even indirectly, can accelerate demands for national liberation.

Finally, the British system of rule in Egypt during Abbas II's time – the "veiled protectorate" characterized by indirect control exercised through a nominally sovereign local ruler under the watchful eye of a powerful British representative – offers a model for understanding subsequent forms of neo-colonial influence.

This pattern, where formal political independence coexists with significant external economic, political, or military constraints, has been replicated in various forms across the post-colonial world, highlighting the enduring complexities of achieving and maintaining genuine sovereignty in an unequal international system.

Table 1: Timeline of Key Events in the Life and Reign of Khedive Abbas II

| Date(s) | Event | Source(s) |

| 14 July 1874 | Birth of Abbas Hilmi II (Alexandria or Cairo) | |

| c. 1884 - 1892 | Education in Cairo, Geneva (Haxius School), Vienna (Theresianum) | |

| 8 January 1892 | Accession as Khedive of Egypt and Sudan following death of father, Tewfik Pasha | |

| 1892 | Islamic Charitable Association established; Al-Hilal newspaper founded | |

| January 1893 | Dismisses PM Mustafa Fahmi; crisis with Lord Cromer over cabinet appointments | |

| January 1894 | "Frontier Incident": Criticizes British officers; forced apology to Kitchener/Cromer | |

| 19 February 1895 | Marries Ikbal Hanim | |

| 1896 - 1898 | Reconquest of Sudan under Kitchener, funded/manned largely by Egypt | |

| 1898 | National Bank of Egypt established; Agricultural Society established | |

| 1898/99 - 1902 | Construction of Aswan Low Dam | |

| 1899 | Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement for Sudan signed | |

| 1900 | Second visit to Britain; declares readiness to cooperate; Al-Liwa' newspaper founded by Mustafa Kamel | |

| 1902 | Egyptian Arab Land Bank established; Aswan Low Dam completed | |

| 1904 | Anglo-French Entente Cordiale gives Britain free hand in Egypt | |

| June 1906 | Dinshaway Incident occurs | |

| 1907 | Lord Cromer retires; Sir Eldon Gorst appointed; National Party formally established; Al-Jarida founded | |

| 1908 - 1911 | Period of cooperation between Abbas II and Gorst | |

| 8 Nov 1908 - 21 Feb 1910 | Boutros Ghali Pasha serves as Prime Minister | |

| 20/21 February 1910 | Assassination of Prime Minister Boutros Ghali Pasha | |

| 1910 | Divorces Ikbal Hanim; marries Djavidan Hanem | |

| 1911/12 - 1914 | Lord Kitchener appointed Consul-General; renewed conflict with Abbas II | |

| 1912 | Oil discovered in Egypt; Aswan Low Dam first heightening completed | |

| 1913 | Organic Law creates new Legislative Assembly; divorces Djavidan Hanem | |

| July 1914 | Abbas II in Constantinople; wounded in assassination attempt; WWI begins | |

| Nov 1914 | Ottoman Empire joins Central Powers; Abbas II supports Ottomans | |

| 18 December 1914 | Britain declares Protectorate over Egypt | |

| 19 December 1914 | Abbas II formally deposed by the British; uncle Hussein Kamel appointed Sultan | |

| 1914 - 1944 | Life in exile (primarily Switzerland) | |

| 1930 | Publishes The Anglo-Egyptian Settlement | |

| 12 May 1931 | Formally abdicates claim to the throne | |

| 19 December 1944 | Dies in Geneva, Switzerland |

Table 3: Selected Economic and Social Indicators, Egypt (c. 1892-1914) (Note: Data availability for this specific period is limited in the provided sources.Figures are indicative and subject to limitations of historical statistics.)

| Indicator | Period / Year(s) | Data / Trend | Source(s) |

| Population | 1897 | ~9,715,000 (Census) | |

| 1907 | ~11,287,000 (Census) | ||

| General Trend | Rapid population growth noted post-cotton boom, potentially straining resources by early 1900s | ||

| Cotton Sector | Late 19th C | Significant boom, major export earner (e.g., 80% foreign exchange earnings later estimate) | |

| Early 1900s-1914 | Onset of 'cotton crisis': Declining yields due to factors like waterlogging, salinity, pests, despite continued importance. Shift in cotton types cultivated (e.g., Sakellaridis to Achmouni) reflects market responses. Agricultural output growth decelerated 1900-1914. | ||

| Cost of Living Index (Rural) | 1892 | 99.91 (Base 1900=100) | |

| (Selected years, Base 1900=100) | 1895 | 77.18 | |

| 1900 | 100.00 | ||

| 1905 | 103.40 | ||

| 1910 | 111.47 | ||

| 1913 | 133.64 | ||

| 1914 | 132.12 | ||

| National Debt | By 1914 | Reached over £100 million, partly due to earlier expansion costs (e.g., infrastructure for cotton) | |

| Government Budget | 1892-1914 | Detailed annual budget figures for this specific period are not readily available in the provided sources. Earlier (1833) and later periods show reliance on land tax and agriculture. |

8. Conclusion

The reign of Khedive Abbas Hilmi II stands as a critical and complex chapter in the history of modern Egypt, encapsulating the inherent tensions of governance under imperial domination.

Ascending the throne as a young, European-educated ruler in 1892, he inherited a Khedivate whose theoretical autonomy was fundamentally undermined by the reality of British occupation.

Throughout his twenty-two years in power, Abbas II engaged in a persistent, multifaceted struggle to assert Khedivial sovereignty and navigate the powerful currents of Egyptian nationalism, while simultaneously presiding over significant modernization efforts often intertwined with British imperial interests.

His early reign was characterized by direct, albeit unsuccessful, confrontations with British authority, embodied by Lord Cromer and Lord Kitchener, particularly over control of the cabinet and the army. These clashes, while resulting in Khedivial setbacks, signaled his refusal to be a mere puppet and resonated with a growing nationalist sentiment.

He employed a dual strategy, attempting to strengthen Egypt internally through infrastructure development (railways, roads, bridges, the Aswan Low Dam), financial institution building, and educational reforms, while also providing support to nationalist figures and the anti-British press.

This approach, however, was constantly constrained by the overarching power of the British Agency and the geopolitical realities of the time, notably the Entente Cordiale, which limited his room for diplomatic maneuver.

The Dinshaway Incident of 1906 proved a crucial turning point, dramatically intensifying popular nationalist feeling and exposing the brutality underlying the occupation. While Abbas II's relationship with the nationalist movement fluctuated, his reign undeniably coincided with, and in part contributed to, its transformation into a major political force.

The brief period of conciliation under Sir Eldon Gorst offered a potential alternative path, but was ultimately cut short by Gorst's death and the deep-seated animosity between Abbas and the returning Lord Kitchener. The outbreak of World War I forced a final, decisive confrontation, leading to Abbas II's deposition and the formal imposition of a British Protectorate in 1914.

His long exile was spent attempting to manage his affairs, influence events from afar, and shape his historical legacy through memoirs and writings, challenging the dominant colonial narrative. The rich archival collection he left behind remains a vital resource for understanding this period from a non-British perspective.

The legacy of Abbas II is contested. He has been viewed as a nationalist symbol who dared to defy the British, a meddlesome obstructionist by colonial officials, a modernizing reformer, and a ruler caught in the impossible bind of exercising authority under foreign occupation.

Perhaps the most accurate assessment positions him as an active, intelligent, and complex figure who embodied the contradictions of his time. He sought to uphold the dignity and authority of the Khedivate and foster Egyptian development, but was ultimately overwhelmed by the structural power of the British Empire and the cataclysm of global war.

His reign did not achieve the sovereignty he sought, but it witnessed and contributed to the processes of modernization and nationalist mobilization that would continue to shape Egypt's trajectory long after his departure.

The struggles over sovereignty, resource control, national identity, and the role of external powers that defined his era remain resonant themes in the history of Egypt and the wider Middle East, highlighting the enduring impact of this pivotal period.

9. References and Sources

- Presidency of Egypt. "Abbas Hilmi II." presidency.eg. https://www.presidency.eg/en/%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%85/%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B3-%D8%AD%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A/#:~:text=He%20was%20born%20on%20July%2014%2C%201874%20in%20Cairo.&text=He%20was%20tutored%20by%20private,in%20the%20Palace%20in%20Cairo.&text=Khedive%20Muhammad%20Tawfiq%20sent%20him,in%20Geneva%2C%20Switzerland%20and%20Vienna.

- Presidency of Egypt. "Abbas Hilmi II." presidency.eg. https://www.presidency.eg/en/%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%85/%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B3-%D8%AD%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A/

- Wikipedia. "Abbas II of Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbas_II_of_Egypt

- Geni. "Al-Amir Abbas Hilmi II, Khedive of Egypt (1892-1914)." geni.com. https://www.geni.com/people/Al-Amir-Abbas-Hilmi-II-Khedive-of-Egypt-1892-1914/6000000015381082640

- Nasser Youth Movement. "Egypt Rulers of Egypt Abbas Helmi II." nasseryouthmovement.net. https://www.nasseryouthmovement.net/Egypt-1838

- Wikipedia. "Prince Abbas Hilmi." en.wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Abbas_Hilmi

- Egy.com. "THE KHEDIVE'S DEMON." egy.com. https://www.egy.com/historica/11-07-28.php

- Mohamed Ali Foundation. "The Archive of Abbas Hilmi II." mohamedalifoundation.org. https://www.mohamedalifoundation.org/the-archive-of-abbas-hilmi-ii

- Mohamed Ali Foundation Fellowship Programme. "The Archive of Abbas Hilmi II." mohamedalifoundation.webspace.durham.ac.uk. https://mohamedalifoundation.webspace.durham.ac.uk/the-archive-of-abbas-hilmi-ii/

- Durham University Library Special Collections Catalogue. "Abbas Hilmi II Papers." reed.dur.ac.uk. https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s18049g504c.xml

- Amazon.com. "Abbas II: 1st Earl of Cromer, Evelyn Baring." amazon.com. https://www.amazon.com/Abbas-Evelyn-Baring-Earl-Cromer/dp/1497432693

- Britannica. "Egypt: Abbas Hilmi II (1892–1914)." britannica.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Abbas-Hilmi-II-1892-1914

- Voutsadakis.com. "Almanac: October 31, 2024." voutsadakis.com. Accessed [Date].https://voutsadakis.com/GALLERY/ALMANAC/Year2024/Oct2024/10312024/2024oct31.html

- Britannica. "ʿAbbās II khedive of Egypt." britannica.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abbas-II-khedive-of-Egypt

- Egypt Independent. "This day in history: Abbas Helmy II becomes Egypt's Khedive." egyptindependent.com. Accessed [Date].https://egyptindependent.com/day-history-abbas-helmy-ii-becomes-egypt-s-khedive/

- AMAR Foundation. "Khedive Abbas Ḥilmi II." amar-foundation.org. Accessed [Date].https://www.amar-foundation.org/020-khedive-abbas-%E1%B8%A5ilmi-ii/

- Wikipedia. "Khedivate of Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khedivate_of_Egypt

- 1914-1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War. "Egypt." encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Accessed [Date].https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/egypt/

- National Library of Israel. "Abbas II, Khedive of Egypt, 1874-1944." nli.org.il. Accessed [Date].https://www.nli.org.il/en/a-topic/987007257328505171

- AUC Bookstores EG. "The Last Khedive of Egypt: The Memoirs of Abbas Hilmi II." aucbookstores.com. Accessed [Date].https://aucbookstores.com/products/9789774249945

- Cromer, Evelyn Baring. Abbas II. London: Macmillan and Co., 1915. (Accessed via McMaster University repository).https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/14780/1/fulltext.pdf

- Khaled Fahmy Blog. "The Great Theft of History: The Egyptian Army in the First World War." khaledfahmy.org. Accessed [Date].https://khaledfahmy.org/en/2019/11/11/the-great-theft-of-history-the-egyptian-army-in-the-first-world-war/

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. "Abbas Hilmi ['Abbās Ḥilmi] II (1874–1944), last khedive of Egypt [Image]." oxforddnb.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.oxforddnb.com/abstract/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-39071?mediaType=Image

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. "Abbas Hilmi ['Abbās Ḥilmi] II (1874–1944), last khedive of Egypt." oxforddnb.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.oxforddnb.com/abstract/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-39071

- Encyclopedia.com. "Abbas II." encyclopedia.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.encyclopedia.com/reference/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/abbas-ii

- Wikipedia. "Abbas I of Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbas_I_of_Egypt

- Great Militaria & Collectors Forum. "Help with Egyptian Khedive medal." gmic.co.uk. Accessed [Date].https://gmic.co.uk/topic/69654-help-with-egyptian-khedive-medal/

- Wikipedia. "Muhammad Ali dynasty." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_dynasty

- Wikipedia. "Muhammad Ali dynasty family tree." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_dynasty_family_tree

- Almanach de Gotha. "Egypt - The Muhammad Ali Dynasty." almanachdegotha.org. Accessed [Date].https://www.almanachdegotha.org/id248.html

- Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia. "MUHAMMAD 'ALI DYNASTY." ccdl.claremont.edu. Accessed [Date].https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1403

- New World Encyclopedia. "Muhammad Ali Dynasty." newworldencyclopedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Muhammad_Ali_Dynasty

- Wikimedia Commons. "Category:Muhammad Ali dynasty." commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Muhammad_Ali_dynasty

- Geni. "Muhammad Ali Pasha, Wāli of Egypt." geni.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.geni.com/people/Muhammad-Ali-W%C4%81li-of-Egypt/6000000010269519914

- DeviantArt. "Muhammad Ali Dynasty Monarchs." deviantart.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.deviantart.com/benjiskyler/art/Muhammad-Ali-Dynasty-Monarchs-982753804

- Royal Ark. "Egypt: The Muhammad 'Ali Dynasty - Genealogy." royalark.net. Accessed [Date].https://www.royalark.net/Egypt/egypt.htm

- Magers & Quinn Booksellers. Product listing referencing Muhammad Ali Dynasty. magersandquinn.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.magersandquinn.com/product/MUHAMMAD-ALI-DYNASTY/7402817

- Britannica. "Egypt: Abbas Hilmi II (1892–1914)." Internal Analysis based onhttps://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Abbas-Hilmi-II-1892-1914.

- Britannica. "ʿAbbās II khedive of Egypt." Internal Analysis based onhttps://www.britannica.com/biography/Abbas-II-khedive-of-Egypt.

- El-Gammal, Maged. "The Denshwai Incident of 1906 Revisited: Justice or Order?" Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Arts 16, no. 1 (2019). Accessed viahttps://jaauth.journals.ekb.eg/article_47948_e9693401e690d52757949ff39152dbeb.pdf

- Encyclopedia.com. "Dinshaway Incident." encyclopedia.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/dinshaway-incident

- Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC). "The Eagle and the Crescent: A History of U.S.-Egyptian Relations." (2012). Accessed viahttps://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA592772.pdf

- Scholar Publishing. "The Denshawai Incident and its Impact on Egyptian Nationalism." Academic Social Science Research Journal. Accessed viahttps://journals.scholarpublishing.org/index.php/ASSRJ/article/download/7891/4828/19474

- Britannica. "Dinshaway Incident." britannica.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.britannica.com/event/Dinshaway-Incident

- Encyclopedia.com. "Dinshaway Incident (1906)." encyclopedia.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/dinshaway-incident-1906

- Wikipedia. "Denshawai incident." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denshawai_incident

- Oxford Reference. "Dinshaway Incident." oxfordreference.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.oxfordreference.com/abstract/10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001/acref-9780195176322-e-448

- Wikipedia. "Abbas II of Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbas_II_of_Egypt.

- British Empire. "Abbas Hilmi." britishempire.co.uk. Accessed [Date].https://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/abbashilmi.htm

- Malak, Karolin. "The Last Khedive but the First to Decolonise? Abbas Hilmi II’s Odyssey for Sovereignty." Durham Middle East Papers No. 109 (April 2024). Accessed viahttps://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP109---The-Last-Khedive-but-the-First-to-Decolonise.pdf

- Artware Fine Art. "Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener." artwarefineart.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.artwarefineart.com/archive/gallery/field-marshal-horatio-herbert-kitchener-1st-earl-kitchener-khartoum-1850-1916

- Moseley, Sydney A. With Kitchener in Cairo. London: Cassell and Company, 1917. (Accessed via Wikimedia Commons).https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/04/With_Kitchener_in_Cairo_%28IA_withkitchenerinc00mose%29.pdf

- Cromer, Evelyn Baring. Abbas II. London: Macmillan and Co., 1915..https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/14780/1/fulltext.pdf

- Michigan State University Libraries. Etd Record 42970. d.lib.msu.edu. Accessed [Date].https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/42970

- Durham University Library Special Collections Catalogue. "Abbas Hilmi II Papers." reed.dur.ac.uk. Accessed [Date].https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s18049g504c.xml.

- Valkoun, Jaroslav. "Czech-Egyptian Relations During the Reign of Khedive Abbas Hilmi II." Studia Orientalia Slovaca 12, no. 2 (2013). Accessed viahttps://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/bitstream/10831/74512/1/Jaroslav%20Valkounpdf-a-237-254.pdf

- Belgeler: Türk Tarih Belgeleri Dergisi. Abstract of "Lord Cromer's Book 'Abbas II'..." (December 2024). belgeler.gov.tr. Accessed [Date].https://belgeler.gov.tr/eng/abstarct/116/eng

- Amazon.com. "Abbas II by Evelyn Baring Cromer (Earl of)." amazon.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.amazon.com/Abbas-Evelyn-Baring-Cromer-Earl/dp/102156723X

- Amazon.com. "Abbas II: 1st Earl of Cromer, Evelyn Baring." amazon.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.amazon.com/Abbas-Evelyn-Baring-Earl-Cromer/dp/1497432693.

- Willgallis, Mara. Egypt's Occupation: Colonial Economism and the Crises of Capitalism. Stanford University Press, 2020. (Excerpt accessed via sup.org).https://www.sup.org/books/middle-east-studies/egypts-occupation/excerpt/excerpt-introduction

- Britannica. "Egypt: Abbas Hilmi II (1892–1914)." britannica.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Abbas-Hilmi-II-1892-1914.

- Owen, Roger. Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul. Oxford University Press, 2004. (Abstract/related content accessed via ResearchGate).https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375327858_Lord_Cromer_Victorian_Imperialist_Edwardian_Proconsul

- LitCharts. "Lord Cromer Character Analysis in Orientalism." litcharts.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.litcharts.com/lit/orientalism/characters/lord-cromer

- African Affairs. Review/Correspondence related to Lord Lloyd's Egypt Since Cromer. Vol. XXXII, No. CXXVII (April 1933). Accessed via academic.oup.com.https://academic.oup.com/afraf/article-pdf/XXXII/CXXVII/219/257406/XXXII-CXXVII-219.pdf

- Wikipedia. "Boutros Ghali." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boutros_Ghali

- Mary Evans Prints Online via Media Storehouse. "Boutros Pasha Ghali." mediastorehouse.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.mediastorehouse.com/mary-evans-prints-online/boutros-pasha-ghali-4465343.html

- SuperStock. "Boutros Ghali... assassinated on 20th February 1910." superstock.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.superstock.com/asset/boutros-ghali-prime-minister-egypt-who-assassinated-th-february-ibrahim/4220-20416015

- Egy.com. "The Assassination of Boutros Ghali Pasha." egy.com. Accessed [Date].http://www.egy.com/people/96-09-18.php

- Hansard. UK Parliament Debates, Commons Written Answers, 20 April 1910. "Murder Of Boutros Ghali Pasha (Egypt)." hansard.parliament.uk. Accessed [Date].https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1910-04-20/debates/8365d6d6-e9da-44e3-8a25-359c40ba3428/MurderOfBoutrosGhaliPasha(Egypt

- ResearchGate. Abstract of "Death of a Prime Minister: The Assassination of Boutros Ghali..." (September 2024). researchgate.net. Accessed [Date].https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384480015_Death_of_a_Prime_Minister_The_Assassination_of_Boutros_Ghali_and_Mediating_Sectarianism_in_Egypt_1906-1911

- Hansard. UK Parliament Debates, Commons Written Answers, 16 March 1910. "Egyptian Vernacular Press (Murder Of Boutros Ghali Pasha)." hansard.parliament.uk. Accessed [Date].https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1910-03-16/debates/1108c0fa-ab01-4360-9ac2-b67ad760fdc5/EgyptianVernacularPress(MurderOfBoutrosGhaliPasha

- Wikipedia. "Abbas II of Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbas_II_of_Egypt.

- Mohamed Ali Foundation. "The Archive of Abbas Hilmi II." mohamedalifoundation.org. Accessed [Date].https://www.mohamedalifoundation.org/the-archive-of-abbas-hilmi-ii.

- Durham University Library Special Collections Catalogue. "Abbas Hilmi II Papers." reed.dur.ac.uk. Accessed [Date].https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s18049g504c.xml.

- The National Archives Discovery. Entry for Abbas Hilmi II. discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Accessed [Date].https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/c/F281778

- Mohamed Ali Foundation Fellowship Programme. "The Archive of Abbas Hilmi II." mohamedalifoundation.webspace.durham.ac.uk. Accessed [Date].https://mohamedalifoundation.webspace.durham.ac.uk/the-archive-of-abbas-hilmi-ii/.

- International Conference on Restoration of Architectural Heritage, Geo-spatial Technology, Earth Observation and Cultural Heritage. Paper referencing Abbas Hilmi II's building activities. scholarsmine.mst.edu. Accessed [Date].https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2938&context=icrageesd

- Malak, Karolin. "The Last Khedive but the First to Decolonise? Abbas Hilmi II’s Odyssey for Sovereignty." Durham Middle East Papers No. 109 (April 2024)..https://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP109---The-Last-Khedive-but-the-First-to-Decolonise.pdf

- University of Texas Libraries Repository. Thesis referencing Abbas Hilmi II archive. repositories.lib.utexas.edu. Accessed [Date].https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstreams/99384a91-eb92-42e2-a8d6-71849d941f74/download

- Wikipedia. "Cotton production in Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cotton_production_in_Egypt

- Economic History Society. "Overcoming the Egyptian cotton crisis in the interwar period..." ehs.org.uk. Accessed [Date].https://ehs.org.uk/overcoming-the-egyptian-cotton-crisis-in-the-interwar-period-the-role-of-irrigation-drainage-new-seeds-and-access-to-credit/

- Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO). Paper referencing 1833 Egyptian budget. ide.go.jp. Accessed [Date].https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Periodicals/De/pdf/72_02_04.pdf

- Economic Research Forum (ERF). Working Paper 0211. erf.org.eg. Accessed [Date].https://erf.org.eg/app/uploads/2017/05/0211.pdf

- Williamson, Jeffrey G. Appendix to "Globalization and Inequality Then and Now..." (Data appendix). scholar.harvard.edu. Accessed [Date].https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jwilliamson/files/1842appendix.pdf

- Wikipedia. "Economy of Egypt." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Egypt

- CIA Reading Room. Declassified document on Egyptian agriculture (post-WWII context). cia.gov. Accessed [Date].https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP79R00890A000700080001-1.pdf

- Colorado Department of Education. Resource on Aswan Dam. cde.state.co.us. Accessed [Date].https://www.cde.state.co.us/standardsandinstruction/aswandam

- International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID). "Aswan Dam." icid-ciid.org. Accessed [Date].https://icid-ciid.org/award/his_details/69

- Britannica. "Aswan High Dam." britannica.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aswan-High-Dam

- Wikipedia. "Aswan Low Dam." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aswan_Low_Dam

- eBay listing description referencing Aswan Dam history. ebay.com. Accessed [Date].https://www.ebay.com/itm/176877173427

- Wikipedia. "Aswan Dam." en.wikipedia.org. Accessed [Date].https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aswan_Dam

- Visitegypt.com. "Where Is Aswan Dam Located?" visitegypt.com. Accessed [Date].https://visitegypt.com/where-is-aswan-dam-located/

- Chalcraft, John. "Under Surveillance: Policing and Politics in Khedive Abbas Hilmi II’s Egypt." Durham Middle East Papers No. 104 (2022). Accessed viahttps://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP104---Under-Surveillance.pdf

- International Journal of Middle East Studies. Review of Matthew Ellis, Desert Borderland. cambridge.org. Accessed [Date].https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-middle-east-studies/article/matthew-ellis-desert-borderland-the-making-of-modern-egypt-and-libya-stanford-calif-stanford-university-press-2018-pp-280-6500-cloth-isbn-9781503605008/206FC3BA783E231892111EFC6862695C

- Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Asian History. "Economic History of the Modern Middle East, 1869–1945." oxfordre.com. Accessed [Date].https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-506?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190277727.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190277727-e-506&p=emailA600b9g95PsRo

- Moubayed, Sami. "Abbas Hilmi II's Nomination for the throne of Syria 1930-1932." Durham Middle East Papers No. 110 (April 2024). Accessed via Durham Repository.https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/2443074/abbas-hilmi-iis-nomination-for-the-throne-of-syria-1930-1932

- Malak, Karolin. "The Last Khedive but the First to Decolonise? Abbas Hilmi II’s Odyssey for Sovereignty." Durham Middle East Papers No. 109 (April 2024)..https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/2443183/the-last-khedive-but-the-first-to-decolonise-abbas-hilmi-iis-odyssey-for-sovereignty

- Environmental History. Article referencing Aswan Dam and empire. journals.uchicago.edu. Accessed [Date].https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1093/envhis/emz078

- Metropolitan Museum Journal. "The Sacred and the Modern: The History, Conservation, and Science of the Madina Sitara." (December 2017). Accessed via ResearchGate.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321804025_The_Sacred_and_the_Modern_The_History_Conservation_and_Science_of_the_Madina_Sitara

- Ellis, Matthew. Desert Borderland: The Making of Modern Egypt and Libya. Stanford University Press, 2018. (Excerpt accessed via sup.org).https://www.sup.org/books/middle-east-studies/desert-borderland/excerpt/introduction

- El-Kateb, Ahmed. "Historicizing space and mobilization: Khedive Abbas Hilmi II and the Egyptian student movement in exile (1914–1922)." Durham Middle East Papers No. 108 (April 2024). Accessed viahttps://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP108---Historicizing-space-and-mobilization.pdf

- Durham University Library Special Collections Catalogue. Overview of collections including Sudan Archive. reed.dur.ac.uk. Accessed [Date].https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ead/uni/unde.xml

- Michigan State University Libraries. Etd Record 14792. d.lib.msu.edu. Accessed [Date].https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/14792

Works cited

- The Archive of Abbas Hilmi II - Mohamed Ali Foundation, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.mohamedalifoundation.org/the-archive-of-abbas-hilmi-ii

- The Archive of Abbas Hilmi II - Mohamed Ali Foundation Fellowship Programme - Durham University, accessed April 25, 2025, https://mohamedalifoundation.webspace.durham.ac.uk/the-archive-of-abbas-hilmi-ii/

- `Abbas Hilmi II papers - Durham University, accessed April 25, 2025, https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s18049g504c.xml

- Copyright by Kristin Shawn Tassin 2014 - University of Texas at Austin, accessed April 25, 2025, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstreams/99384a91-eb92-42e2-a8d6-71849d941f74/download

- Durham Middle East Papers, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP104---Under-Surveillance.pdf

- Taqadum Al-Khatib - Historicizing space and mobilization: The last khedive of Egypt and the Egyptian student movement - Durham Middle East Papers, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP108---Historicizing-space-and-mobilization.pdf

- Abbas II of Egypt - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbas_II_of_Egypt

- Abbas Helmi II - Nasser Youth Movement, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.nasseryouthmovement.net/Egypt-1838

- Khedive of Egypt and Sudan - ztab1, accessed April 25, 2025, https://voutsadakis.com/GALLERY/ALMANAC/Year2024/Oct2024/10312024/2024oct31.html

- Aswan Dam | International Commission on Irrigation & Drainage (ICID), accessed April 25, 2025, https://icid-ciid.org/award/his_details/69

- Aswan Low Dam - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aswan_Low_Dam

- Egypt - Abbas Hilmi II, Ottoman Rule, Modernization | Britannica, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Abbas-Hilmi-II-1892-1914

- Abbas Hilmi - The British Empire, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/abbashilmi.htm

- Karim Malak - The Last Khedive but the First to Decolonise? Abbas Hilmi II's Odyssey for Sovereignty - Durham Middle East Papers, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/school-of-government-amp-int-affairs/DMEP109---The-Last-Khedive-but-the-First-to-Decolonise.pdf

- Š‡ ”‹–‹•Š ƒ † ‰›'– ‹ –Š‡ ͷ;ͿͶ•1 - EDIT (ELTE), accessed April 25, 2025, https://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/bitstream/10831/74512/1/Jaroslav%20Valkounpdf-a-237-254.pdf

- December 2018 -- No.2. Page : ( 13- 20 ) - ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ - The Executions at Denshwai on 28 July 1906 in the sight of the British Authorities - Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, accessed April 25, 2025, https://jaauth.journals.ekb.eg/article_47948_e9693401e690d52757949ff39152dbeb.pdf

- Dinshaway Incident | Encyclopedia.com, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/dinshaway-incident

- The Arab Spring in Egypt: What are the Implications for U.S. Foreign Policy - DTIC, accessed April 25, 2025, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA592772.pdf

- Denshawai and Cromer in the poetry of Ahmad Shawqi - Scholar Publishing, accessed April 25, 2025, https://journals.scholarpublishing.org/index.php/ASSRJ/article/download/7891/4828/19474

- Dinshaway Incident | British Occupation of Egypt 1906 - Britannica, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Dinshaway-Incident

- Dinshaway Incident (1906) | Encyclopedia.com, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/dinshaway-incident-1906

- Denshawai incident - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denshawai_incident

- Dinshaway Incident - Oxford Reference, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.oxfordreference.com/abstract/10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001/acref-9780195176322-e-448

- Abbas II. - MacSphere, accessed April 25, 2025, https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/14780/1/fulltext.pdf

- ʿAbbās II | Reign of Abbas II, Modernization, Reforms | Britannica, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abbas-II-khedive-of-Egypt

- This day in history: Abbas Helmy II becomes Egypt's Khedive, accessed April 25, 2025, https://egyptindependent.com/day-history-abbas-helmy-ii-becomes-egypt-s-khedive/

- Egypt - 1914-1918 Online, accessed April 25, 2025, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/egypt/

- Abbas II, (1874-1944) | The National Library of Israel, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.nli.org.il/en/a-topic/987007257328505171

- The Last Khedive of Egypt: The Memoirs of Abbas Hilmi II - AUC Bookstores, accessed April 25, 2025, https://aucbookstores.com/products/9789774249945

- Muhammad Ali dynasty - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_dynasty

- Muhammad Ali Dynasty - New World Encyclopedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Muhammad_Ali_Dynasty

- Muhammad Ali Dynasty Monarchs by BenjiSkyler on DeviantArt, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.deviantart.com/benjiskyler/art/Muhammad-Ali-Dynasty-Monarchs-982753804

- Abbas Hilmi II - Egy.com, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.egy.com/historica/11-07-28.php

- Khedivate of Egypt - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khedivate_of_Egypt

- Abbas II | Encyclopedia.com, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/reference/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/abbas-ii

- Muhammad Ali dynasty family tree - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_dynasty_family_tree

- Kingdom of Egypt - House of Muhammad 'Ali - Almanach de Saxe Gotha, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.almanachdegotha.org/id248.html

- Muhammad 'Ali Dynasty - Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/1403

- Desert Borderland: Introduction | Stanford University Press, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.sup.org/books/middle-east-studies/desert-borderland/excerpt/introduction

- Al-Amir Abbas Hilmi II, Khedive of Egypt (1892-1914) (1874 - 1944) - Genealogy - Geni, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.geni.com/people/Al-Amir-Abbas-Hilmi-II-Khedive-of-Egypt-1892-1914/6000000015381082640

- 020 – Khedive 'Abbās Ḥilmī II « AMAR Foundation for Arab Music Archiving & Research, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.amar-foundation.org/020-khedive-abbas-%E1%B8%A5ilmi-ii/

- Category:Muhammad Ali dynasty - Wikimedia Commons, accessed April 25, 2025, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Muhammad_Ali_dynasty

- Wāli Muhammad Ali Pasha Pasha of Egypt (Uthman) (1769 - 1849) - Genealogy - Geni, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.geni.com/people/Muhammad-Ali-W%C4%81li-of-Egypt/6000000010269519914

- Egypt - Royal Ark, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.royalark.net/Egypt/egypt.htm

- Muhammad Ali Dynasty: Farouk of Egypt, Abbas II of Egypt, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.magersandquinn.com/product/MUHAMMAD-ALI-DYNASTY/7402817

- Abbas II: 1st Earl of Cromer, Evelyn Baring,: 9781497432697: Amazon.com: Books, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Abbas-Evelyn-Baring-Earl-Cromer/dp/1497432693

- Egypt's Occupation: Excerpt from Introduction | Stanford University Press, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.sup.org/books/middle-east-studies/egypts-occupation/excerpt/excerpt-introduction

- Matthew Ellis, Desert Borderland: The Making of Modern Egypt and Libya (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2018). Pp. 280. $65.00 cloth. ISBN: 9781503605008 | International Journal of Middle East Studies | Cambridge Core, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-middle-east-studies/article/matthew-ellis-desert-borderland-the-making-of-modern-egypt-and-libya-stanford-calif-stanford-university-press-2018-pp-280-6500-cloth-isbn-9781503605008/206FC3BA783E231892111EFC6862695C

- Abbas Hilmi II, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.presidency.eg/en/%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%85/%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B3-%D8%AD%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A/

- Review and Translation of Lord Evelyn Baring Cromer's Abbas II - Belgeler, accessed April 25, 2025, https://belgeler.gov.tr/eng/abstarct/116/eng

- Abbas Ii: Evelyn Baring Cromer (Earl Of): 9781021567239: Amazon.com: Books, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Abbas-Evelyn-Baring-Cromer-Earl/dp/102156723X

- Lord Edward quotes an unverinable obiter dictum of Cromer's on, accessed April 25, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/afraf/article-pdf/XXXII/CXXVII/219/257406/XXXII-CXXVII-219.pdf

- Abbas Hilmi II's Nomination for the throne of Syria 1930-1932, accessed April 25, 2025, https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/2443074/abbas-hilmi-iis-nomination-for-the-throne-of-syria-1930-1932

- The Last Khedive but the First to Decolonise? Abbas Hilmi II's Odyssey for Sovereignty, accessed April 25, 2025, https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/2443183/the-last-khedive-but-the-first-to-decolonise-abbas-hilmi-iis-odyssey-for-sovereignty

- Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul - ResearchGate, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375327858_Lord_Cromer_Victorian_Imperialist_Edwardian_Proconsul

- Lord Cromer Character Analysis in Orientalism - LitCharts, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.litcharts.com/lit/orientalism/characters/lord-cromer

- Capitalism, Growth, and Social Relations in the Middle East: 1869–1945 | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, accessed April 25, 2025, https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-506?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190277727.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190277727-e-506&p=emailA600b9g95PsRo

- www.presidency.eg, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.presidency.eg/en/%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%85/%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B3-%D8%AD%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A/#:~:text=He%20was%20born%20on%20July%2014%2C%201874%20in%20Cairo.&text=He%20was%20tutored%20by%20private,in%20the%20Palace%20in%20Cairo.&text=Khedive%20Muhammad%20Tawfiq%20sent%20him,in%20Geneva%2C%20Switzerland%20and%20Vienna.

- Abbas Hilmi, II, (b1941), Egyptian and Imperial Ottoman prince and financial manager, accessed April 25, 2025, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/c/F281778

- Aswan High Dam | Description, History, Capacity, Problems, & Facts | Britannica, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aswan-High-Dam

- Al-Sadd al-ʿĀlī Manteqet ORIGINAL ASWAN DAM PHOTO EGYPT NILE RIVER VINTAGE, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.ebay.com/itm/176877173427

- Aswan Dam - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aswan_Dam

- Where Is Aswan Dam Located? Discover Egypt's High Dam Site - visit Egypt, accessed April 25, 2025, https://visitegypt.com/where-is-aswan-dam-located/

- Aswan Dam, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.cde.state.co.us/standardsandinstruction/aswandam

- Cotton production in Egypt - Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cotton_production_in_Egypt

- Overcoming the Egyptian cotton crisis in the interwar period: the role of irrigation, drainage, new seeds and access to credit - Economic History Society, accessed April 25, 2025, https://ehs.org.uk/overcoming-the-egyptian-cotton-crisis-in-the-interwar-period-the-role-of-irrigation-drainage-new-seeds-and-access-to-credit/

- egypt's growth performance under economic liberalism: a reassessment with new gdp estimate, accessed April 25, 2025, https://erf.org.eg/app/uploads/2017/05/0211.pdf

- THE EGYPTIAN ECONOMY - CIA, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP79R00890A000700080001-1.pdf